Sex and the Data Bill

Beware of building digital identities on sand.

The government’s new data verification services framework has a critical flaw: government data itself is not trustworthy when it comes to the core personal characteristic of sex.

One-page summary

The government has introduced the Data (Use and Access) Bill,1 which it says will boost the UK economy by £10 billion over 10 years, save millions of staff hours in the police and NHS, and make it easier for people to do business and access services. Core to it is a framework for “data verification services” (DVS) to allow people to exchange verified personal information about themselves easily without relying on paper documents.

Sex is an important fact about an individual, which is often necessary to share and record for reasons including safety, fairness, dignity, privacy and safeguarding, in situations including health and social care, sport, criminal justice and access to single-sex services.

There is a critical flaw in the design of the DVS framework: government data itself is not trustworthy when it comes to the core personal characteristic of sex. The Data Bill will set up a trustmark for private-sector services to handle people’s data. But government bodies such as the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency, Passport Office and NHS Personal Demographic Service, which are relied on as “authoritative sources”, would fail to meet the standard.

Unless the problem with these authoritative sources is addressed, the DVS system will be unreliable, costly and dangerous. It will lead to people being locked out of services they should be able to use and being treated dangerously in areas such as healthcare, and public servants having to undertake costly, inefficient and dangerous workarounds to record information outside the system. It will fail to deliver savings or facilitate economic growth.

Conversely, the shift to digital identities creates an opportunity for a simpler, more coherent system for recording sex accurately, while allowing people to keep their information private when it is not needed. The problems with the incoherent data and confusion over sex and gender identity can and must be addressed to protect everyone’s rights.

The new legislation provides the opportunity to build in data protection by design and by default for sex data.

We call on the Secretary of State to ensure this risk and opportunity are addressed in the Data (Use and Access) Bill, and by the Office for Digital Identities and Attributes.

Introduction

The government has introduced the Data (Use and Access) Bill2 through which it aims to boost the UK economy by £10 billion across 10 years and free up millions of staff hours in the police and NHS, saving hundreds of millions of pounds and making it easier for people to do business and access services while protecting their privacy.

The bill provides a statutory basis to standardise how personal data is recorded, making it easier for information to flow safely, securely and seamlessly within public services and across health and social care, and between public and private data systems, based on individual consent.

The benefits the government promises include:

- cutting down on bureaucracy for police officers saving around £42.8 million and 1.5 million hours a year keying in data

- making patients’ data easily transferable across the NHS freeing up 140,000 hours of NHS staff time every year

- simplifying important tasks for citizens such as renting a flat or entering employment by enabling a system of digital identity verification to allow people to verify their identity and facts about them without using paper documents.

The government is clear that the aim is not to create a new mandatory digital ID system or to introduce “ID cards”, but rather to provide the basis for a decentralised system for standardised recording, verification and sharing of personal information that will protect people’s privacy. For this system to work, it is crucial that safeguards are put in place to secure the accuracy of the data and ensure it is stored and used in ways that do not breach people’s privacy.

Sex is an important piece of personal identity information. It is both part of a person’s foundational identity recorded when they were born, and an attribute about them which needs to be recorded accurately and shared in situations including health and social care, criminal justice and sport. Unless the digital identity system assures accuracy in the recording of sex, it will fail to deliver savings, enable safety and convenience or secure trust.

What is a digital identity?

A digital identity is a digital representation of a person’s identity information, such as their name and date of birth. It enables people to prove who they are without presenting physical documents. At the individual’s request, it can also contain other information about them such as their address, their qualifications or the fact that they have a particular bank account.

Figure 1: Digital identity example

Unlike a physical document, digital identity allows the individual to limit the information they share in any particular situation to only what is necessary. For example, if they are asked to prove they are 18 or over, they could do this by unlocking an app on their phone with their fingerprint, and showing a QR code that provides a simple Yes/No response and avoids sharing any other personal details.

Attributes are pieces of information that describe something about a person or organisation. Attributes can help people prove that they are who they say they are, or that they are eligible or entitled to do something.

New legislation and standards

Work on rules and systems for digital identity verification is ongoing. The government has set up a new Office for Digital Identities and Attributes within the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) to enable the development of a trusted and secure digital identity market in the UK.3 A version of the UK digital identity and attributes trust framework is already in use.4 This is a set of rules and standards in areas including privacy, data protection, fraud management, cybersecurity and inclusivity. The trust framework aims to set stringent rules.

The Data (Use and Access) Bill will establish a statutory basis for implementation of the framework. The bill will enable the Secretary of State to establish and govern a new register of service providers. These providers will be independently certified against the trust framework and will be able to get a “trust mark”.

The trust framework provides that identities are underpinned by authoritative data sources. Currently this most commonly involves scanning drivers licences and passports. The Bill will enable the the creation of an information gateway so that public bodies such as the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) and His Majesty’s Passport Office (HMPO) will be able to share information directly with registered organisations to enable them to carry out identity or eligibility checks for a member of the public. This information may be released only on the request of the individual to whom the information relates.

Human rights and data-protection principles

The Data (Use and Access) Bill and the systems enabled by it should align with existing data-protection legislation and data-protection principles, and be compatible with human rights.

Article 5(1) of the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)5 provides that personal data shall be:

- processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner in relation to individuals

- collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes

- adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which they are processed (“data minimisation”)

- accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date

- kept in a form which permits identification of data subjects for no longer than is necessary for the purposes for which the personal data are processed (“storage limitation”)

- processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security of the personal data, including protection against unauthorised or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction or damage, using appropriate technical or organisational measures (“integrity and confidentiality”)

- handled in a way that ensures appropriate security, including protection against unlawful or unauthorised processing, access, loss, destruction or damage.

The problem is that these standards are already being flouted when it comes to information about whether a person is male or female (that is, their sex). If an organisation mixes different items of data in the same field, such as sex and gender identity – with different meanings, definitions, uses and privacy requirements – it is impossible for that organisation to control this data in line with the principles.

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights provides6 that everyone has the right to respect for their private and family life, their home and their correspondence. It protects both a person’s privacy and their ability to validate their identity.

It provides there shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health of morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

This does not mean that a person has absolute freedom to determine what data is recorded against their identity and how it is used. This is illustrated by a legal case concerning a person’s date of birth.7 A refugee wished to have what he claimed was an incorrect date of birth changed on a biometric immigration identity card. He was on hunger strike and suicidal, and said the data recorded was “dehumanising and corrosive of his sense of identity”. Nevertheless, the judge ruled:

“A public authority’s record-keeping function must respect the Article 8 rights of individuals, but that does not extend to inserting information in records which is not supported by evidence and is considered, on good grounds, to be inaccurate and misleading. This must be the case no matter how serious the consequences for a particular individual.”

The judgment highlights that an important reason public authorities should not put unverified, inaccurate or misleading information into official records is the public interest in accurate, evidence-based records overall. Yet every common source of what should be authoritative personal data makes this fundamental error when it comes to the sex attribute.

The problem with sex data

An immutable attribute

Sex is a physiological attribute about a person that is determined at conception and observed at (or before) birth. Sexual reproduction, the generation of offspring by fusion of genetic material from two different individuals, one male and one female, evolved over a billion years ago – long before humans, words or laws. It is the reproductive strategy of all mammals as well as other higher animals and plants. Like other mammals, human females produce eggs and gestate live young. Males produce sperm to fertilise the female egg. In accordance with their respective reproductive roles, females and males have different reproductive anatomies (this is sometimes termed “biological sex” or “sex recorded at birth” to disambiguate from other uses of the word “sex”).8

The Gender Recognition Act 2004 means it is possible that a person’s “certified sex” as recognised in law can be changed for some purposes.9 However, an individual’s actual sex remains an immutable feature that is important throughout their lifetime.10

The data is corrupted

In practice the information that is currently recorded as “sex” (or “gender” as a synonym) by many public and private bodies is neither accurate nor reliable. In most cases it neither reflects biological sex nor certified sex, but has been replaced by information representing “gender identity” (for more detail see Appendix 2). For example:

- Passport – recorded sex can be changed with a doctor’s note indicating that the person wishes to live “as the opposite gender” – 3,188 records known to be affected over the last five years.11

- Biometric residence card – a person’s recorded sex can be changed if their name is changed by deed poll or if the “sex” marked on their home-country passport is changed.

- Driving licence – a person’s recorded sex can be changed on request: it does not appear on the face of the driving licence, but is encoded in the licence number – 15,481 records known to be affected over the last six years.12

- NHS records – a person’s recorded sex can be changed on request, after which a new NHS number is issued.

- UK birth certificate – this records either a person’s actual sex or their sex as modified by a gender-recognition certificate – 8,464 records known to be affected over the last 20 years.

A gender-recognition certificate (GRC) enables a person to get a new birth certificate and to change the sex recorded against their identity by HM Revenue & Customs and the Department for Work and Pensions. Although only around 8,500 GRCs have been issued,13 according to the last censuses in England and Wales and Scotland there are about 100,000 people who identify as a “transgender man” or a “transgender woman”14 (although there are some concerns about the accuracy of this data).15 More than 15,000 driving licences were changed between 2018 and 2023 – more than four times the number of GRCs issued over the same period. What is clear is that there are people whose sex recorded on official records does not accord with their actual sex, including many with a range of official records that record their sex differently.

Apart from those people obtaining a new birth certificate via the Gender Recognition Act, this has happened in an ad-hoc manner outside any legislation. It has been done according to differing criteria and at the discretion of a wide range of government departments and agencies, including the Home Office, Ministry of Justice, HM Passport Office, the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency, the National Health Service Personal Demographics Service and NHS trusts. No systematic records have been kept, so it is impossible to tell from either the face of an identity document such as a passport or driving licence or the underlying records whether the sex of the person holding the identification is recorded accurately.

No-one’s sex records as held by HMPO, DVLA or the NHS can currently be treated as reliable. But the digital identity and attributes trust framework treats these as authoritative sources.

Bad data causes harm

Even though someone’s actual sex is usually readily perceptible in person (and a person with a transgender identity may be open about being transgender), inaccurate and unreliable records create problems, confusion and significant risks of harm and liability.

- People with mismatched identities risk being flagged up as a “synthetic identity” risk. This could lead to transgender people being excluded from services such as banking or renting property.

- Authorities with statutory safeguarding responsibilities will be unable to robustly assess risk related to the sex of children or vulnerable people, and the sex of potential abusers. Children’s and vulnerable people’s healthcare records can be lost if they identify as transgender and change their NHS number.

- Illnesses may be misdiagnosed, treatments may be misprescribed and medical risks may fail to be identified if the wrong sex is stated in a person’s medical records.

- People will be unable or less likely to access services for their sex (such as cervical and prostate screening services) if they are recorded as the wrong sex.

- When questions cannot be targeted accurately by sex, time is wasted, communications are inaccurate and risks cannot be properly managed. For example, everyone who is having an X-ray must be asked if they might be pregnant because the administrative recording of patients’ sex is inaccurate.

- Police and others aiding law enforcement risk being unable to identify people who have been recorded as the wrong sex.

- Disclosure and Barring Service checks may fail to match an individual with their criminal record because of searching the wrong “gender”.

- Service providers will be less able to use data-verification services to create value in the economy and meet social needs, because those digital IDs do not contain reliable sex information.

- People risk being placed unexpectedly and non-consensually in intimate situations with members of the opposite sex, causing discomfort, humiliation and exposure.

- Official data will not be a sound basis for proving eligibility for the female sporting category, meaning that it may be used to evade sex-based rules and undermine the fairness and safety of women’s sport.

In order to resolve the problem of data systems that do not have a simple, accurate sex field, data users develop work-arounds that waste time and introduce complexity and risk. This problem was identified as a serious issue by the NHS as long ago as 2009, but since then it has only worsened.16

The government’s trust framework has not yet addressed the issue

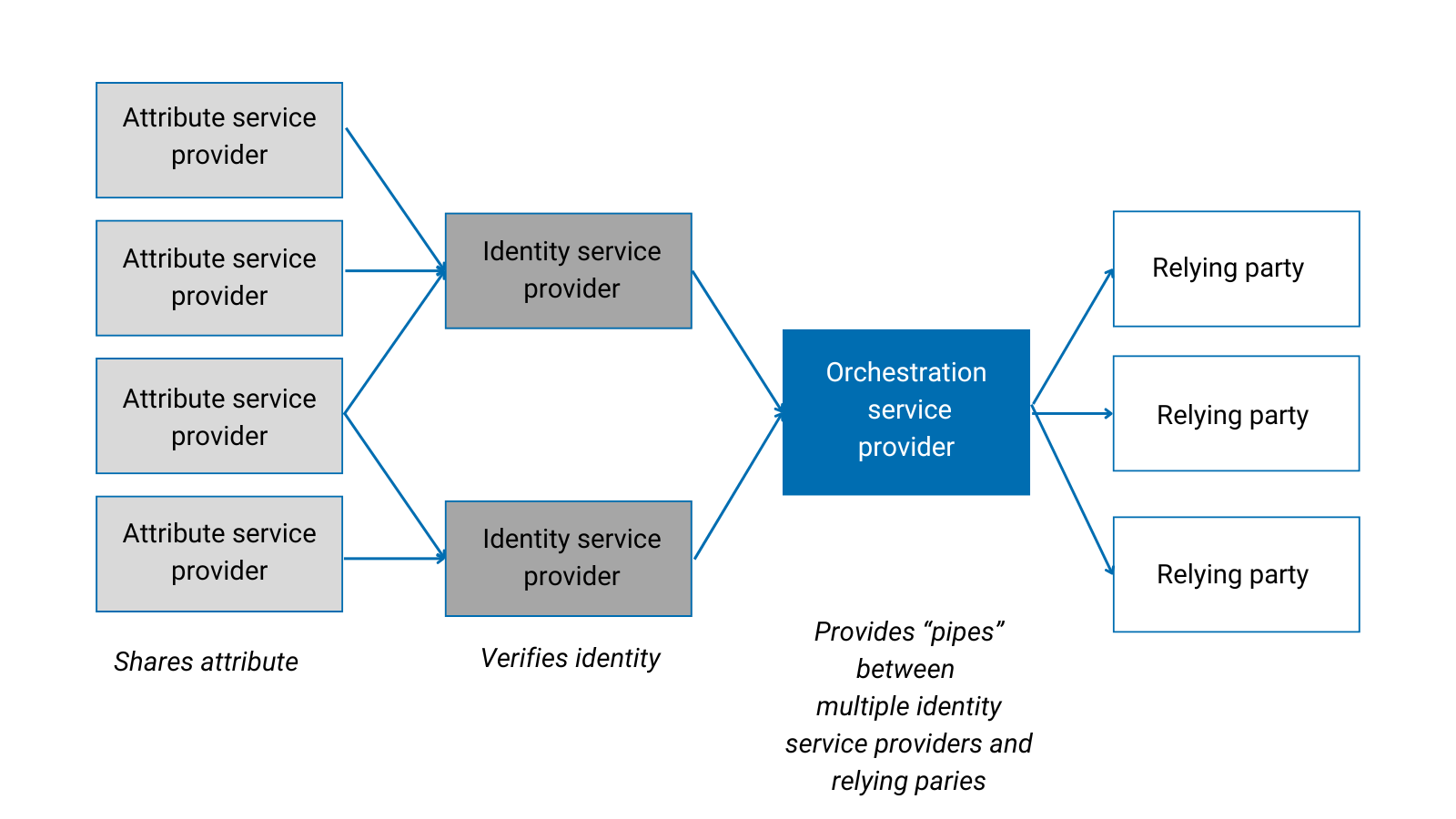

The latest version of the UK digital identity and attributes trust framework was updated on 20th July 2023 (beta version 0.3).17 It describes a system in which identity service providers and attribute service providers can interact to enable individuals to prove that they are who they say they are, and to prove key facts about themselves.

Figure 2: Schematic of relationship between trust framework participants18

The system relies on underlying authoritative sources of information such as passports and driving licences.19 However, nowhere in the current guidance is it explained that neither a passport or a driving licence can currently provide authoritative information on a person’s sex. In relation to attributes, the framework simply says “gender” instead of sex, and does not recognise that this is not an adequate description of the attribute of sex.

If one attribute service provider uses “gender” to mean biological sex (male or female), another records male and female (as recognised by HMRC, including by virtue of a GRC) in a field marked “sex” and a third records “male” or “female” alongside “non-binary”, “transwoman” and several other possible self-descriptions in a field marked “gender identity”, it will be impossible for them to exchange data robustly, or for anyone to rely on it.

The UK GDPR requires organisations to consider data-protection concerns in every aspect of their processing activities, an approach known as “data protection by design and by default”. The practice of mixing immutable objective sex, legally certified sex including via a GRC, and mutable subjective gender identity in the same field is a barrier to this approach. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has yet to comment on the issues of data protection in relation to the sex attribute; but it has said that it will continue to provide regulatory advice to the government on data-protection matters in relation to the development of the digital verification services scheme.20 It should be asked to provide urgent advice on the problems with the sex attribute.

The Data (Use and Access) Bill provides for the development of an information gateway, which will provide a way for individuals to validate their personal information directly by providing consent for it to be checked using an automated process with the DVLA, HMPO or other participating public agency such as HMRC or the Registrar General. It seems likely (although this has not been acknowledged as an issue by the Office of Digital Identities and Attributes) that the information gateway, if it relies initially on HMPO, DVLA and HMRC, would be unable to respond to any request for a person’s biological sex, since none of these sources can authoritatively return an “F” only for people who are actually female, or an “M” only for people who are actually male.

The digital identity system as it is currently conceived will therefore provide a useless and dangerous mix of unreliable information and no information at all on individuals’ sex. Rather than cutting costs, it will create new costs, since anyone who needs to know and record service users’ sex will have to create ad-hoc solutions and complex workarounds. These include frontline healthcare workers, police officers, workers in women’s refuges and gym staff, who must routinely recognise and record whether a person they are dealing with is male or female.

The system is being built on sand. The Data Bill will enable the Secretary of State to establish a register of private-sector identity-verification service providers. But the reality is the public bodies that provide the bedrock of the data-verification system are currently unfit to meet the government’s own trust standard in relation to the “sex” attribute.

A way forward

Official data systems are in such a mess in relation to sex because of decades of ad-hoc, informal and incremental measures attempting to accommodate the wishes and protect the privacy of people who identify as transgender. A particular concern has been to allow people to access services where having an apparently mismatched identity could in the past have caused problems, embarrassment or exclusion. An example is a person with a female name and feminine dress style trying to travel on a passport that stated their sex as “male”. Responding to this problem by misrecording sex was not only an unsatisfactory solution, but one for an analogue age. Not only did it create knock-on problems, but the digital revolution now makes it unnecessary.

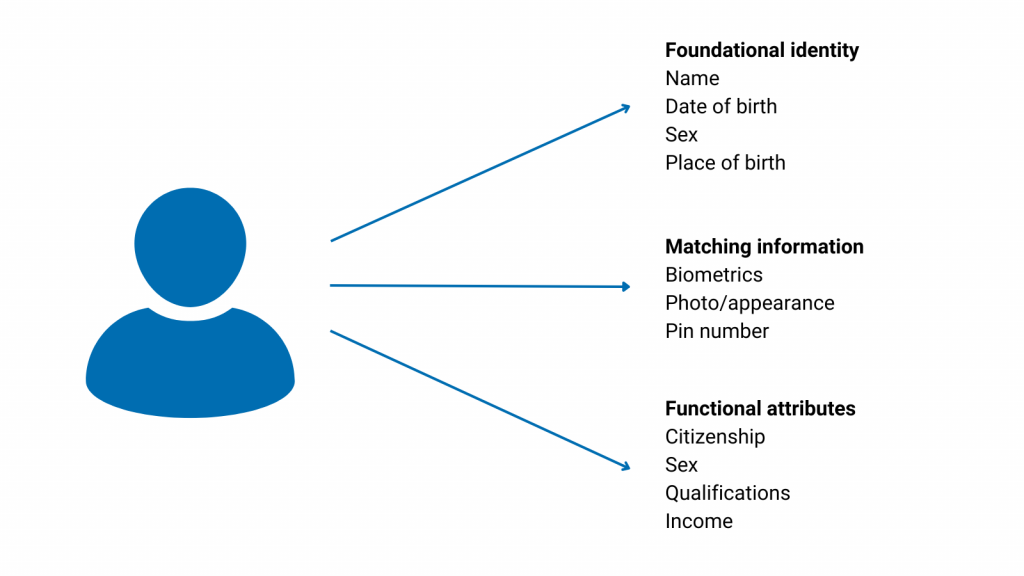

Solving the problem in a way that protects everyone’s rights means starting by recognising that sex has historically been used as part of identity Information in three ways:

- foundational identity recorded at birth

- matching information that is used to determine that a particular person owns the identity (for example that the person with a female record looks or sounds like a woman)

- functional attribute about a person to be used where a person’s sex is relevant information for a transaction, entitlement or service, for instance in healthcare, social services and sport.

Figure 3: Three types of identity data

The crucial difference between a system built on decentralised digital identity and one based on paper credentials, a database or a register is that each attribute can be treated separately. In a digital system the user needs to reveal only the pieces of information needed for a particular interaction. For example, there is no need to share whether someone is male or female when they are proving they are over a certain age or have a right to rent, or to use a person’s sex as matching information where other reliable checks exist.

But having a false or erroneous piece of information recorded in the sex field is a serious problem, which leads to unnecessary and costly system failures. Digital attributes are created, collected and checked by an attribute service provider for one purpose, but can then be used for another. Unless the data definitions are standardised and information quality is assured, the whole data set becomes degraded and potentially dangerous because it cannot be relied on to be accurate.

Principles for inclusive, accurate digital identity

A digital identity framework which works for everyone would ensure that:

- Sex remains clear and accurate as part of the foundational identity of every individual.

- Every individual can validate their sex as a functional attribute in situations where sex matters.

- Organisations can validate any individual’s sex when that information is needed and they have consent (or for other overriding reasons such as criminal investigation or safeguarding).

- Every individual can keep information about their sex private in transactions for which that information need not be shared.

- People who have changed their recorded sex in some legacy systems are not excluded from using digital identity systems that rely on accurate sex data.

Sex data can sometimes be kept private

The solution is for sex data to be treated like all other personal information. There is no heroic effort needed to keep information such as your name and date of birth secret; they are merely not shared when not needed. The same approach should be taken for sex.

With a digital identity system each individual attribute will be revealed, checked or shared only for a particular use. Except when the information is needed for a legal investigation or to save someone’s life, it remains controlled by the individual. Where data on a person’s sex does not need to be seen or recorded by the relying party, it need not be shared at (for example an age-verification app does not need to reveal a person’s sex, or their name or other information about them).

This does not stop people from noticing what sex someone else is when meeting them in person, or from acting on that information.

One of the most common use-cases for sex is as “matching information”, or to avoid duplicate information. For example the DVLA says:

”By providing us with gender details we can ensure we reduce the number of instances when surnames, initials and dates of birth match. This is a security measure to prevent duplicated records.”21

Sex matching can be a rough-and-ready indicator of fraud – for example if someone who looks or sounds like a man tries to use an identity marked as female this may set off red flags for a “synthetic ID” or using someone else’s identity. Although being male or female is not a strong personal identifying feature (it is shared with half the population), it is often used because a common security risk is a husband or wife using their partner’s identity, for example to access their bank account.

However, data on sex is not the only, or even the most reliable, way to be sure that someone owns an identity. And digital systems can use other reliable matching information such as biometrics.

Airports now use facial recognition. Gatwick Airport, for example, says that all passengers must provide proof of identity when checking in for their flight but that “it does not matter if your current gender presentation matches that given on your documentation or that of your photograph”.22 Identity cards from many European countries do not have a sex marker on the face of the card.

Another illustration of privacy protection without compromising security is Mastercard’s “True Name” initiative, which enables people to use their preferred name on credit, debit and prepaid cards.23

Often name, date of birth and sex are used to match someone to their data (such as when booking an appointment online or checking in at the GP’s office using a touch screen). The government’s previous “Verify” framework made the “gender” field optional as a matching data set (that is, one of the pieces of data used to identify a unique individual).24 The “gender” attribute was also removed as required matching data in the NHS Personal Demographic Service API. This meant that the developers of the Covid-19 vaccination booking service were able to allow people to book appointments without filling in a question about their sex (while maintaining the link to their sex as stated in their medical records).25

Approaches like these avoid embarrassing transgender people by not requiring or displaying sex data when it is not needed, without confusing or falsifying data. They achieve this by using only the data necessary for the particular situation.

When sex data is needed it should be accurate

Everyone knows which sex they are, and other people can almost always tell. Where this information is needed, for most purposes an honest answer to a straightforward question will suffice. The trust framework should require that organisations that record data are clear about the definition of sex and do not collude in misrecording a person’s sex when they know the sex that person has reported is inaccurate (for example when self-report suggests that the person’s sex has changed over time).

Sex can also be validated by a more formal observation or assessment. This may be biological in situations where greater assurance is needed. A person’s doctor and other healthcare professionals will know their patients’ sex for certain, and should be expected to record it accurately in a clearly defined field. For female athletes, a cheek swab can be used to robustly determine sex chromosomes.26 Chromosome tests, while individually simple, would be costly, unwieldy and unnecessary for application to the entire population, but they can be used, for example, in sports. The results of a cheek-swab test can be securely attached to a person’s identity, so needs to be done only once in a lifetime.

For people born in the UK, the most reliable and straightforwardly accessible record of their sex remains the birth register. Sex is recorded at birth. For people born in the UK this is done using the birth notification system,27 which results in the allocation of an NHS number. A baby’s sex is recorded in their personal child health record (PCHR), also known as “the red book”, and then in the birth register, along with place and date of birth, name, and details about the parents (the child’s birth mother, and the father or second legal parent).28 This forms their foundational identity. An electronic birth register (which the Data Bill provides for) would allow the information gateway to bypass the corrupted records of the DVLA and HMPO and consult an individual’s birth record (with consent) in order to verify their sex.

Appendix 1 sets out a series of use cases describing how digital identity verification services that provide accurate sex data, with ordinary privacy, would work in practice.

Why immediate action is needed

Unless the digital identity system assures accuracy in recording of sex it will fail to gain trust, deliver savings or facilitate economic growth.

Solving the problem with sex data is both urgent and doable. To avoid chaos and capitalise on opportunities, the government needs to recognise the need for accurate sex data and design it into the digital identities and attributes trust framework, including the core data standard and the information gateway.

This will take leadership.

- The government must make clear that enabling accurate everyday verification of sex is a policy objective, and give clear policy direction to officials in the Office for Digital Identities and Attributes.

- Parliament should consider amendments to the Data Bill to ensure that sex data is defined clearly and can be verified.

- The Office for Digital Identities and Attributes should investigate the issue, convene stakeholders and publish a technical paper proposing a practical approach.

- The Information Commissioner’s Office should provide detailed commentary on whether current data systems are in breach of data-protection principles, and on the proposed approach.

The fundamental problem is the need for authoritative data sources. This can be solved.

- The Bill makes provision for digital birth records. When connected to the information gateway, this register can provide an accurate source of sex data.

- HMPO and DVLA records on sex must be excluded from the gateway and the attribute verification standard unless and until they start recording sex accurately again.

- The Bill makes provision for a new health and social care data standard. This must also ensure that sex is recorded accurately, to provide another authoritative source.

This solution would mean that individuals and organisations are able to have clear records of sex, and that sex is treated like other aspects of personal identity, in line with data-protection principles.

Unless the problem is addressed, the DVS system will be unreliable, costly and dangerous. It will risk members of the public being locked out of services they should be able to use and being treated dangerously, including when accessing healthcare. Organisations in the public and private sector will have to create costly, inefficient and dangerous workarounds to record information outside the system.

Conversely, the shift to digital identities creates an opportunity for a simpler, more coherent system that protects everyone’s rights.

We call on the Secretary of State to ensure this risk and opportunity are addressed in the Data (Use and Access) Bill and by the Office for Digital Identities and Attributes.

Appendix 1: Use-cases for digital verification of sex information

Communal space

A mixed-sex group of friends are organising a walking holiday, staying in a series of youth hostels. On some nights they book to stay in a private bunk room together as a group, and on others they book beds in male and female dorms shared with other travellers. Each of the party is a member of the Youth Hostel Association and when they joined they used a digital identity to validate their details, including their sex. The YHA’s online booking system uses this to make sure that only male members are booked in the male dorms and only female members in the female dorms.

Medical records

A fracture clinic asks patients to log in with their name and their date of birth on a screen when they arrive for an appointment. It uses this to match them with their medical records. They do not need to key in their sex. Their sex is not displayed on the landing screen of their records that is seen by the receptionist; however, it is seen by their doctor, who can view their full details. Frank is a transman – that is, a female person who identifies as a man. Frank feels comfortable checking in for medical appointments. Frank receives invitations for the correct screenings, such as cervical smear tests. Healthcare professionals dealing with Frank are able to consider risk factors associated with being female (such as the possibility that Frank might be pregnant when undergoing an X-ray).

Bodily contact

Mina is a self-employed beautician who provides intimate waxing services from her home. She advertises that she will provide this service only to women. As part of the booking process, she asks clients to log in with a digital identity that includes information on their sex, and she checks their identity using an app when they arrive. This helps Mina feel safe in providing her service.

Online dating

Jamila is a lesbian. She joins a dating app. On joining she validates that she is female using her digital identity. As part of the registration process she indicates that she is only interested in being introduced to other women (female people). Saskia is bisexual. She joins the dating app and indicates that she is interested in being introduced to people of either sex. Zile is pansexual and genderqueer. Zile does not wish to disclose zer sex as Zile does not believe sex is important. Therefore, on joining the dating app Zile chooses not to provide this information. Zey will not be matched with either Jamila or Saskia, but will be matched with other users of the app who have indicated that they do not need to know the sex of people they may meet for dates.

Shared space

Frieda rents out property to paying guests using an online service. She has a holiday cottage that she lets out and has guests to stay with her in her home. While anybody can book the cottage, for those staying in her home she specifies only female guests, as they are sharing her living space. The service validates the identity of all guests booking but requires information on sex only from those who are seeking to book properties that are restricted on this basis.

Workplace security

A workplace uses a digital ID system for entry and for logging onto the IT system by fingerprint. Yusuf is gender-fluid and sometimes identifies as Yasemin. The employers’ data system includes both Yusuf’s legal name and nickname, as well as Yusuf’s sex. When entering the building the automatic gate recognises Yusuf/Yasemin’s fingerprint. Both names can be seen by security staff on screen, together with a photograph. Information on Yusuf/Yasemin’s sex is not immediately visible on screen, but could be accessed if needed.

Social care

Denise and Alex are both carers who work for a domiciliary care agency. The agency uses an app-based system to match available carers and send them to people’s homes to provide personal care. When Denise and Alex joined the agency, they validated their sex as part of the safeguarding and onboarding process. Denise is a woman and Alex is a man. Many of the agency’s clients are elderly women who have indicated that they want to receive intimate care only from female care workers. Some clients have indicated that this is their preference, but they will accept a male carer. Others have indicated that they do not mind either way. The care agency’s app is able to match Denise and Alex with clients according to the clients’ preferences. The app sends a notification to the client that the carer has been allocated before the booking is confirmed, and it includes their name, photo and sex as well as information about when this carer has visited before. A client is able to accept or reject that carer, either on this particular occasion or permanently, before the carer sets off to visit the client.

Sporting categories

Selina, who is 16, is a keen athlete. She competes in her school team, trains with her local running club, competes at county level and aims to qualify for the youth national games. She hopes to go on to compete at European and Olympic level. She is registered with England Athletics through her local running club, and her running times in heats and competitions are recorded against her registration number. Her sex and date of birth were recorded when she first registered, based on her showing her birth certificate to the registration secretary of her club. This allows her to enter races in her correct age and sex class. She knows that if she qualifies for the national team she will need to consent to and undertake a test by a cheek swab to confirm she has 46XX (female) chromosomes. This is a one-time test and the data will be added to her registration to secure the integrity of women’s sports competitions.

Age verification

A digital ID system is available for people to validate their age at the supermarket or pub for the purposes of buying alcohol. This works through a digital identity “wallet” that is activated by a fingerprint scanner on a phone. The app generates a QR code that can be scanned by retail staff to receive confirmation that the person is over 18 years old. These staff do not see any further details such as name, sex or photograph. Stephanie is transgender: a male person who wishes to be treated socially as female. Although showing an ID that states Stephanie’s sex as male would not reveal any information that is not visible to a casual observer, doing so nevertheless makes Stephanie feel uncomfortable, and has led to unwelcome comments in the past. Using the digital app avoids sparking awkward conversations.

Notes

Note that in all these examples, the data in the “sex” attribute is treated in exactly the same way whether the person has a trans identity or not. Therefore nothing is flagged up and no special status is needed. Nor is the fact that someone identifies as transgender recorded or assessed. Rather, sex is treated like any other attribute and used or shared only with consent or for a legitimate reason where consent is not required, such as in the course of a criminal investigation. This is in line with ordinary data-protection principles.

Service providers may also record the fact that a person identifies as transgender, if the person has shared this information and provided consent for its use, as well as other user-provided data such as the person’s title and preferred pronouns. This information may be helpful in enabling transgender people to be accommodated without requiring sex to be misrecorded on identity systems.

Appendix 2: Mapping the sex data problem

This appendix looks in more detail at how sex is currently allowed to be misrecorded in official ID and data systems.

Passports

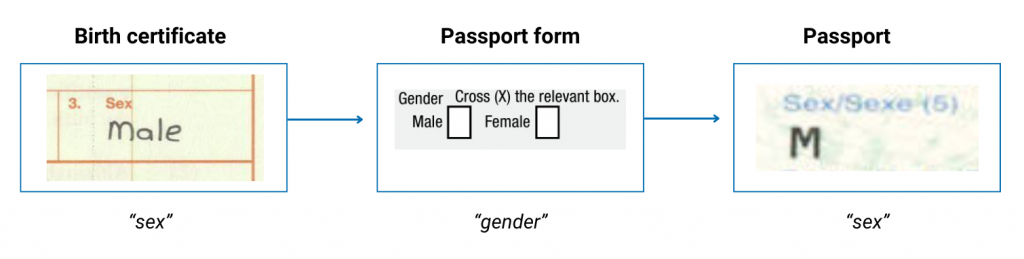

When a person applies for a UK passport, they must tick one of two boxes marked “gender” – the options are “male” or “female”. In most cases the source document for this is the person’s birth certificate, which shows their sex. There is no legal definition of “gender” and no defined objective property called “gender” about a person. On the passport itself, male or female is displayed as “sex” in line with international passport standards. Thus what is recorded on a passport in the first instance is a person’s sex as recorded on their birth certificate.

Figure 4: How sex data is described for passports

However, the Passport Office allows a person to apply to have the sex recorded on their passport changed to display the marker of the opposite sex. They must send in a doctor’s letter “confirming that the orientation to the acquired gender is likely to be permanent”. These letters are basic, and a template can be downloaded from support organisations and signed during a seven-minute GP appointment, by either an NHS or a private practitioner. No medical or surgical treatment is required: simply a declaration by a person to a doctor that they intend to permanently adopt the social gender of the opposite sex (for example by changing their name and title).

Therefore, a passport that says “Sex – F” can be held by a person who is either male or female. Similarly, a passport that says “Sex – M” can be held by a person who is either female or male.

Passports are issued at the discretion of the Home Secretary in exercise of Royal Prerogative. The decision to allow the sex recorded on a passport to be changed in this way was not made by Parliament or by courts. At first it was negotiated on an individual basis, with the first known case being in the 1960s when Arthur Cameron Corbett, the third Baron Rowallan, asked for and received a female passport for his fiancée April Ashley, a male-to-female transsexual (at a time when far fewer people held passports).29 This was later formalised as an administrative practice.

The Passport Office now issues guidance leaflets on how to change the recorded “sex” on a passport, in association with groups such as the Gender Identity Research and Education Society (GIRES).30

In response to freedom-of-information requests, the Passport Office has previously stated that it does not know how many people have changed the sex marker on their passport:

“The information you have requested on how many individuals have changed the sex marker on their British passport is not held in a readily available format. To determine whether an applicant has changed their gender on a passport would involve manually searching all our passport records and this would not be possible within the cost limit.”31

More recently it has started to collate this information.

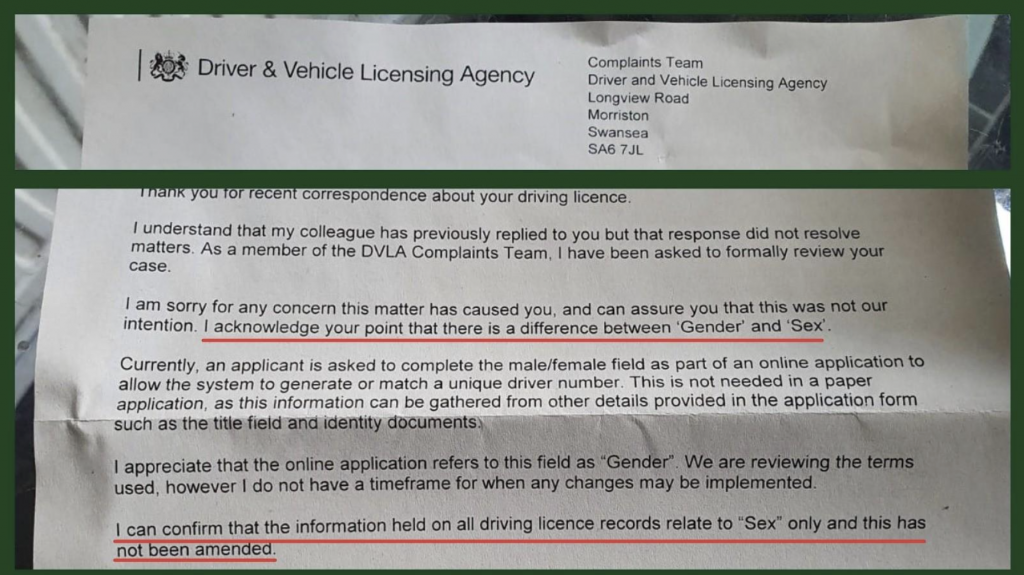

Driving licences

For a driving licence, the application form asks for the applicant’s “gender”: female or male. This information is not shown on the face of the licence, but encoded in a driver number made up of letters of the driver’s name, a code number based on year and month of birth, and their “gender” (the second number is 1 or 2 for a man and 5 or 6 for a woman, depending on the month of their birth).

Figure 5: Driving licence online form gender options

The Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) replied to a customer who complained that the information that is held is “sex” not “gender”.

Figure 6: Letter from the DVLA

However, the recorded “gender” (or “sex”) on a driving licence can be changed by submitting a name-change document (statutory declaration or deed poll) with a covering letter requesting a change of name and a new number. A new driving licence can also be applied for using an existing passport. In this case the “gender” on a driving licence will match the “sex” on the passport (which can be changed with a doctor’s letter).

This policy was brought in in 2002. Before that it was DVLA policy to require supporting evidence from a GP or consultant stating that a person was going through “gender transition”.

This policy was changed following pressure from transsexual support groups. The DVLA says:

“By granting a driving licence, DVLA is not attempting to legally recognise a change of gender and nothing on the driving licence is intended to provide official recognition of gender.”32

Between 2018 and 2023 more than 15,000 driving licence records had the recorded gender changed. It is not known how many were recorded before this, or how many first driving licences are recorded in an acquired gender.

Figure 7: Gender changes on driving licences by year33

| Year | Number of gender changes on driving licences |

| 2018 | 2,467 |

| 2019 | 2,652 |

| 2020 | 2,238 |

| 2021 | 2,191 |

| 2022 | 2,445 |

| 2023 | 3,488 |

| Total | 15,481 |

In 2018 the DVLA said that it was considering the possibility of moving to “gender neutral” driver numbers and driving licences.34

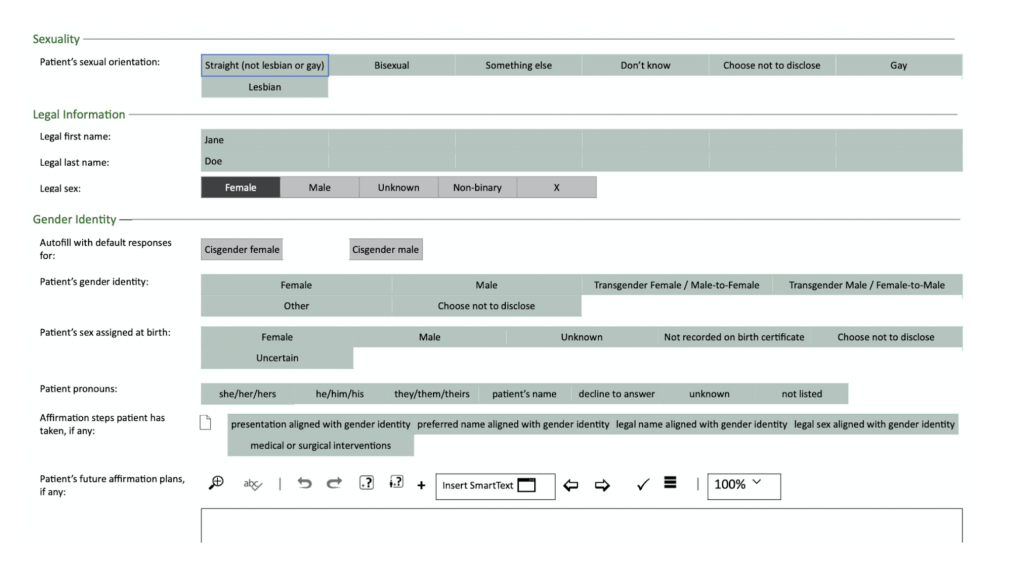

NHS records

In 2009, the NHS recognised the need for clear systems to record biological sex and make sure this was not conflated with social gender. A system of data and definitions that could deal with both was painstakingly created. The data standard explained:

“The term ‘gender’ is now considered too ambiguous to be desirable or safe…”35

It set out definitions for patient “sex” and “current gender” and warned:

“Users may confuse the terms current gender and sex or assume that they are synonymous. Therefore, it is essential that all NHS applications display and explain

current gender and sex terminology and values in a clear and consistent manner.”

The data standard set out in detail how to keep these two characteristics separate and unconfused, and how to design computer interfaces to ensure that sex data was captured (with social gender as an optional extra). It also set out potential consequences of not adhering to these standards. These included:

- The patient is given the wrong treatment as a result of a failure to identify the patient correctly.

- The patient is given the wrong treatment as a result of a failure to match the patient correctly with their artefacts (samples, letters, specimens, X-rays, and so on).

- The patient is given the wrong treatment as a result of a failure in communication between staff, or staff not performing or checking procedures correctly.

- The patient is categorised with a value that cannot be utilised by any other systems.

- The patient is categorised incorrectly from a legal perspective.

- The patient is categorised incorrectly from their perspective.36

Key principles shaping the guidance included displaying information according to existing standards; minimising opportunities for human error; displaying sufficient instructional information to support data quality; promoting consistency across the mix of users, NHS clinical applications and care settings; ensuring reliable and accurate identification of an individual patient record; and minimising opportunities where patient-clinician relationships might be compromised. However, the data standard was not operationalised.

The current NHS data dictionary differentiates “phenotypic sex” (as observed by a clinician) and “patient stated gender”. But in practice “male” and “female” are recorded against “patient stated gender” and the “phenotypic sex” field typically remains empty. The core demographic data on each person’s NHS record is “Person Stated Gender Code” (male/female), but this does necessarily record a person’s sex as recorded at birth.37 New codes have been introduced to deal with the ambiguity, including a “Gender Identity Same at Birth Indicator Code” (Yes/No).

The current validation does not check against gender, when matching an individual with their NHS number and records: it uses name and date of birth.38

The guidance for the NHS Mental Health Services data set says to prioritise the Gender Identity Code and the “Gender Identity Same at Birth Indicator Code” and not directly ask a patient’s biological sex. It states:

“All services should be asking all patients inclusive questions to identify relevant care information. It is not safe to make assumptions about an individual using the Person Stated Gender code.”39

Researchers have reported that NHS data systems link data about a person’s gender identity and how they wish to be addressed (pronouns, titles), so that the only way to change the elements that relate to social interaction rather than physiology is to change gender in the record. For example, one interviewee said:

“Person who is registered as female cannot have a request to be addressed as ‘Mr’ noted in their health record.”40

Policies to allow patients to change their registered “gender/sex” are now embedded across the health service.

- The GMC tells doctors to change a patient’s sex as recorded on medical records on request. This does not require medical diagnosis, anatomical changes or a GRC.41

- Primary Care Support England tells GP surgeries to change a patient’s recorded sex on their medical record on demand at any time, without requiring diagnosis or any form of gender-reassignment treatment. The patient is to be given a new NHS number (a completely new identity in relation to NHS data systems) and previous medical information must be “gender neutralised” and transferred into a newly created medical record. The patient will be sent screening appointments (for example, for cervical smear tests or prostate cancer screening) according to their new gender. That is, they will be invited to attend the wrong screenings and not invited to attend the right ones.42

Several NHS trusts in England use a data system provided by US-based IT company Epic Systems.43 It records as default a person’s “legal sex” (male, female, “non-binary” or X, even though only male or female are recognised as sexes in UK law).44 Data on a person’s actual biological sex can be found further down under “gender identity” in a voluntary field marked “patient’s sex assigned at birth”. If this field is not filled in, then there is no reliable record of the patient’s biological sex.45 Unless other data systems draw on this field and not the field marked “legal sex” or “gender identity”, a patient’s sex may be confused or hidden when it is needed.

Figure 9: Epic screen

Police records

The National Police Chiefs’ Council’s Person, Object, Location, Event (POLE) data framework requires that an individual’s identity is recorded with “4+1” pieces of information – their given name, surname, date of birth, “gender” and contact information. Under “Gender” the options are Male, Female, Trans Male, Trans Female, Non-Binary Intersex, Not Specified and Not Known.46 This is overcomplex and confusing, and combines two pieces of information in a single field – whether the person is male or female and whether they identify as transgender. It also makes it impossible to search for records that relate to an individual’s actual sex, since this is not a field. This may lead to misidentification of suspects, missing persons and others.

Disclosure and Barring Service checks

The Disclosure and Barring Service undertakes criminal-record checks and checks against the “barred list” for individuals applying for particular classes of role in England and Wales (there is a similar service for Scotland). Standard and Enhanced DBS checks include spent convictions and are required for roles with safeguarding considerations including working with children and vulnerable adults such as teaching, health and social care.

Applicants for a DBS fill in their name and other personal details and their “gender” (male or female) together with previous names and addresses. “Gender” here means current self-declared gender. The applicant’s name, gender, previous names and a record of relevant past convictions, cautions, reprimands and warnings found through a search of records are provided on the face of the certificate.

The overall system depends on individuals being honest and comprehensive about declaring previous names. All applicants are required to sign a legal declaration confirming they have disclosed both their current and previous identities. The person checking the form is required to check the individual’s name, date of birth, and address against their documentation and to check the person’s likeness against a photographic identity such as a passport or driving licence. If there is a mistake in the record (for example criminal convictions that relate to the wrong person are returned) the applicant can contest the results. Police may then ask for fingerprints to prove their identity.

A key issue that has been raised by campaigners is the vulnerability of the overall system to sex offenders changing their names (and potentially also their gender) and using this to hide their past record and get access to children and vulnerable people. Research by the BBC found that between 2019 and 2021, over 700 registered sex offenders went missing from the police record.47

In addition, individuals who identify as transgender are able to use the “Sensitive Applications Route” which means they can choose not to have previous names disclosed on the face of the DBS certificate or directly to their employer.48 To do this they contact the sensitive applications team, which sets up a case file related to all their previous identities. This allows all their previous names to be included in the check without being disclosed to their prospective employer.

Campaigners have argued that this makes it easier to hide identities.49 The Disclosure and Barring Service has responded, saying:

“Our Sensitive Applications process introduces no additional risk to DBS checks; it merely affords transgender applicants with the legal protections that they are entitled to.”50

However, the existence of the sensitive application route means that if an individual’s current identity is clearly not the same as their biological sex, the staff member undertaking checks of their previous names is discouraged from asking questions. They must assume that the person has used the “sensitive route” to make full disclosure, but they have no way of checking this. Meanwhile, staff in the sensitive application team lack the local on-the-ground information and face-to-face contact to probe that an applicant has disclosed all previous names.

Over the past five years over 4,000 sensitive DBS checks have been undertaken. It is not known how many transgender applicants have undergone DBS checks outside of the sensitive route.

Figure 9: Sensitive route DBS checks by year51

| Year | Number of sensitive route DBS checks |

| 2019 | 596 |

| 2020 | 708 |

| 2021 | 664 |

| 2022 | 934 |

| 2023 | 1,240 |

| Total | 4,142 |

In response to a freedom-of-information request, the DBS service said that the only difference between an application under the sensitive applications route and the regular route is that an application under the sensitive route “will be checked against both male and female gender within the system whereas a non-transgender application will only be checked against the declared gender”.52

This reveals a critical risk in the DBS system for transgender applicants who choose not to use the sensitive route. A transgender person who is “out” about being transgender and happy not to use the sensitive route will record all their previous names on the form, but the DBS will only search police national computer (PNC) records and the barred list based on their current “gender”. It would therefore miss convictions linked to the person’s previous name because it would be searching for the wrong “gender”. This loophole is not caused by the applicant withholding any information.

A further risk caused by the treatment of the “gender” field is that it is likely to give employers false confidence that they can ignore the sex of an employee when thinking about safeguarding, and to make them fear that they are not legally entitled to ask a person’s sex. But in many roles for which a standard or enhanced DBS check is needed sex matters, for example in relation to providing personal care or intimate care or in searching, or for working in a single-sex setting such as a women’s refuge or providing care on a same-sex basis. In these situations a responsible employer is likely to want to know, record and use information about the sex of the individual, but the DBS certificate and the existence of the sensitive route suggests to them that they cannot. The Equality and Human Rights Commission has confirmed that it is lawful to restrict a role based on actual sex.53 However, in practice there is no administrative means for a potential employer to ask an applicant for verified evidence of their sex. “Safer recruitment” for working with children and vulnerable people, such as in care situations, requires not just a robust process of checking police records, but also having honest and searching conversations about people’s motivations and life history.54 But this is undermined by the design of the DBS system, and its assumption that it is legitimate to hide previous names even when applying for a highly sensitive position.

Birth certificates

The Gender Recognition Act 2004 (GRA)55 allows a person to have a new birth certificate issued which indicates that they were born the opposite sex. This requires a diagnosis of gender dysphoria (with reports from two doctors) and two years’ worth of documentary evidence of “living in the opposite gender” – paperwork such as wage slips, passport, utility bills showing a new name, title or “gender marker”. It can also include letters from employers, voluntary organisations or others. It does not require medical or surgical changes to a person’s body, or a personal appearance before a panel. It is not an assessment that a person “passes” in everyday life as a member of the opposite sex.

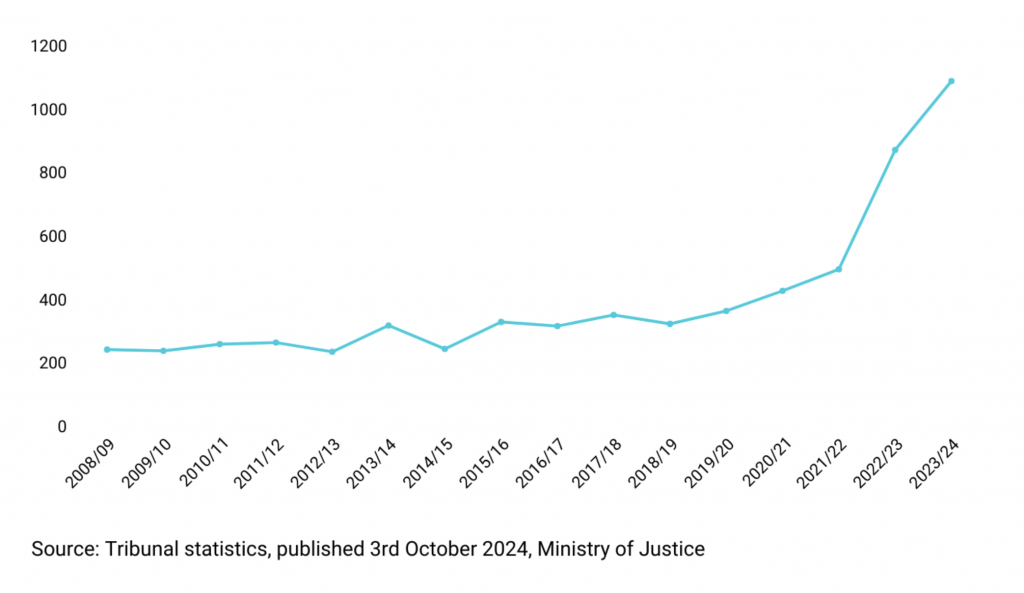

Since the outset of the scheme in 2004, 8,464 full GRCs have been issued. The rate of issuance has recently increased from a fairly steady rate of around 300 a year to 1,088 in the last financial year.56

Figure 10: Number of full GRCs issued per year

When a person receives a GRC, a copy is sent to the appropriate Registrar General (for England and Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland), depending on their birth registration), who makes an entry in the Gender Recognition Register (which is not open to public inspection). This enables the connection between that entry and the entry in the birth register to be traced. The entry is used to create a new birth certificate which records the acquired name and gender.

The ability to change identity in this way creates a risk of identity theft, as it leaves a “discarded identity” in the birth register. This was noted by Lady Hale in the case of C v Secretary of State [2007]:

“There is a particular risk of identity theft in the case of transgender customers. A fraudster may obtain a birth certificate in the customer’s original name and use this, along with other evidence, to obtain a National Insurance number allocated to that name (two linked examples of this were detected in 2012).”

However, for the purposes of digital verification of sex, a person’s original birth registration is an authoritative source.

The GRA does not require that history be rewritten in people’s memory or perception, but Section 22 creates some constraints over direct disclosure of the fact that a person has a GRC. It makes it a criminal offence for a person who has acquired protected information about someone with a GRC while acting in an official capacity to disclose that information to any other person. It provides for specific circumstances (such as for the purpose of a social-security system or in pursuit of crime) in which disclosure without permission is not an offence.

In practice, any information system that records a person’s current legal sex and previous name and title is likely to reveal that they have changed their legal sex.

Organisations that keep a record of a person’s legal sex over time therefore place an extra layer of protection around these records, flagging them as sensitive and often keeping part of the record as a physical file in a locked filing cabinet. For example, the Department of Work and Pensions is required by law to treat people according to their recorded sex when it comes to calculating pension entitlements. It therefore keeps records of a person’s current and previously recorded sex, as well as names. It has a “Special Customer Records Policy” for protecting the records of categories of customers whose information is sensitive. This includes members of the Royal Family, MPs, VIPs, people in high-risk employment, victims of domestic violence and people with witness-protection orders.57 It is applied to anyone who has a GRC (unless they ask for it not to be).

A person who has changed their legal sex through a GRC therefore has records marked as restricted. Customer-service advisors can access them only with permission, with part of the record kept on paper.

This policy was designed to protect the privacy of information, but it has the unavoidable consequence of drawing the attention of frontline staff to its existence. The operation of the policy causes inconvenience and delay in accessing benefits, and advisors may be able to deduce the reason why a customer’s account is flagged as restricted.58

The confidentiality afforded by Section 22 was intended to be limited, and to be applied only to a tiny group of people. In practice, however, it creates problems for any organisation seeking to record information about sex, or to apply straightforward sex-based rules in general, because it makes them afraid to ask, record or act on anyone’s sex in case they might have a GRC. As a result, many organisations do not record anyone’s biological or legal sex at all, instead recording “self-identified gender”. This avoids the potential risk of Section 22 liability, but also makes it impossible to routinely and reliably verify anyone’s sex from their records.

- UK Parliament (2024). ‘Parliamentary Bills: Data (Use and Access) Bill [HL]’.[↩]

- UK Parliament (2024). ‘Parliamentary Bills: Data (Use and Access) Bill [HL]’.[↩]

- UK Government (accessed November 2024). Office for Digital Identities and Attributes.[↩]

- UK Government (2023). UK digital identity and attributes trust framework beta version (0.3).[↩]

- Information Commissioner’s Office (accessed November 2024). A guide to the data protection principles.[↩]

- European Court of Human Rights (2024). Guide on Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.[↩]

- Regina (WA (Palestinian Territories)) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2021].[↩]

- See Bellinger v Bellinger [2003] UKHL 21.[↩]

- For example for the purposes of marriage and pensions (and thus HMRC and DWP records).[↩]

- Very rarely someone’s biological sex may be misdiagnosed at birth.[↩]

- Figures compiled from freedom-of-information requests through Who Do They Know.[↩]

- Figures compiled from freedom-of-information requests through Who Do They Know and Steph Spyro (2024). ‘Changing gender on official papers is “too easy” amid record high for driver’s licences’, Express.[↩]

- Ministry of Justice (2024). Tribunal Statistics Quarterly: April to June 2024.[↩]

- Office for National Statistics (2023). ‘Gender identity’, Data and analysis from Census 2021, and Scotland’s Census (2024). Sexual orientation and trans status or history.[↩]

- Michael Biggs (2024). ‘Gender Identity in the 2021 Census of England and Wales: How a Flawed Question Created Spurious Data’, Sociology, 0(0).[↩]

- NHS (2009). Sex and Current Gender Input and Display User Interface Design Guidance.[↩]

- UK Government (2023). UK digital identity and attributes trust framework – beta version.[↩]

- UK Government (2023). UK digital identity and attributes trust framework – beta version.[↩]

- UK Government (2024). ‘Authoritative sources’, How to prove and verify someone’s identity.[↩]

- Information Commissioner’s Office (2024). Information Commissioner’s response to the Data (Use and Access) (DUA) Bill.[↩]

- Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (2015). Letter from the Strategy Policy and Communications Directorate, What Do They Know.[↩]

- London Gatwick Airport (accessed November 2024) ‘Security screening’.[↩]

- James Issokson (2019). ‘It’s Time to Enable People to Use Their True Name on Cards’, Mastercard.[↩]

- Edgar A Whitley (2018). Trusted digital identity provision: GOV.UK Verify’s federated approach.[↩]

- Sex Matters (2021). ‘NHS: let’s talk about sex’.[↩]

- Ross Tucker, Emma N. Hilton, Kerry McGawley et al (2024). ‘Fair and Safe Eligibility Criteria for Women’s Sport’, Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 34, no. 8 (2024): e14715.[↩]

- NHS England (2024). ‘Birth notification process’.[↩]

- UK Government (1953). Births and Deaths Registration Act 1953.[↩]

- Corbett v Corbett [1970].[↩]

- Home Office Identity & Passport Services (2013). Applying for a passport: Additional information for transgender and transsexual customers.[↩]

- Murray Blackburn Mackenzie (2021). ‘ONS guidance for the sex question in the 2021 census in England and Wales’.[↩]

- Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (2018). Letter in response to freedom of information request FOIR7098, What Do They Know.[↩]

- Figures compiled from freedom-of-information requests through Who Do They Know and Steph Spyro (2024). ‘Changing gender on official papers is “too easy” amid record high for driver’s licences’, Express.[↩]

- Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (2018). Stonewall Workplace Equality index response.[↩]

- NHS (2009). Sex and Current Gender Input and Display User Interface Design Guidance.[↩]

- NHS (2009). Sex and Current Gender Input and Display User Interface Design Guidance.[↩]

- NHS England (2024). Guidance on collecting and submitting data for the data items on gender within the Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS) v5.0.[↩]

- NHS England (2022). CP-IS NHS number matching information.[↩]

- NHS England (accessed November 2024). ‘Data collections and data sets’.[↩]

- Kavya Kartik (2024). ‘“The computer won’t do that” – Exploring the impact of clinical information systems in primary care on transgender and non-binary adults’, Ada Lovelace Institute.[↩]

- General Medical Council (2024). Trans healthcare.[↩]

- NHS Primary Care Support England (accessed November 2024). ‘Adoptions and Gender Reassignment’.[↩]

- Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (2020). ‘MFT signs contract with Epic for ambitious new EPR solution’, 26th May 2020.[↩]

- Epic (2017). ‘More Inclusive Care for Transgender Patients Using Epic’.[↩]

- Sex Matters (2023). ‘An Epic crisis is unfolding in the NHS’.[↩]

- National Police Chiefs’ Council (2023). Minimum POLE Data Standards Dictionary.[↩]

- Alex Homer (2023). ‘Hundreds of UK sex offenders went missing, figures show’, BBC News.[↩]

- UK Government (2022). ‘Transgender applications’.[↩]

- Keep Prisons Single Sex (2022). DBS Checks and Identity Verification: Safeguarding loopholes created by change of identity[↩]

- Hayley Dixon (2022). ‘Trans criminals can use “loophole” to hide previous convictions when applying for jobs’, The Telegraph.[↩]

- Disclosure and Barring Service (2024). Freedom of Information requests, What Do They Know.[↩]

- Disclosure and Barring Service (2024). Letter in response to freedom of information request 2399, What Do They Know.[↩]

- Equality and Human Rights Commission (2024). Guidance on discriminatory adverts.[↩]

- The Safeguarding Toolbox (accessed November 2024). ‘Warner Interviewing’.[↩]

- UK Government (2004). The Gender Recognition Act 2004.[↩]

- Ministry of Justice (2024). Tribunal Statistics Quarterly: April to June 2024.[↩]

- McConnell v The Registrar General for England and Wales [2020] and Department of Work and Pensions(2014). Response to freedom of information request, What Do They Know.[↩]

- McConnell v The Registrar General for England and Wales [2020].[↩]