Guidance for service providers on single-sex services

In the light of the For Women Scotland judgment.

The Equality Act allows service providers to provide single-sex and separate-sex services. Furthermore it expects them to communicate their policies and to expect people to comply with them, so as to protect everyone using single-sex services from discrimination and harassment.

- The Equality and Human Rights Commission published guidance on single and separate-sex services last year.

- Sex Matters has also written guidance for providers of women-only services and a model policy.

Single-sex and separate-sex services are still lawful

The default position of the Equality Act is that in areas of life such as service provision, education and employment, men and women must be treated equally and without discrimination. This means that you cannot generally have a “no women” or “no men” rule in a workplace or business: that would be sex discrimination.

The act provides exceptions (under Schedule 3 paragraphs 26 to 28) that make it lawful to have such rules in order to provide single-sex and separate-sex services in many familiar situations ranging from toilets to women’s refuges. The act also provides a different set of exceptions for single-sex sports, schools, positive action, charities and associations.

Separate-sex services for both sexes (such as toilets, changing-rooms, hospital bays and dormitories) are allowed wherever a joint (meaning mixed-sex or “unisex”) service would be less effective, and as long as the limited provision is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. A legitimate aim could include privacy and dignity.

Single-sex services are also allowed – such as a mobile breast-cancer screening unit for women, a women’s refuge, or a mental-health crisis service for men – as long as the limited provision is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim and it meets one of a list of conditions that include:

- there is a mixed-sex service but to be sufficiently effective a single-sex service is needed as well

- the service is mainly needed by one sex, and a mixed-sex service would be ineffective

- the service is in a hospital, or other care setting

- the service is in a situation where a person of one sex might reasonably object to the presence of a person of the opposite sex.

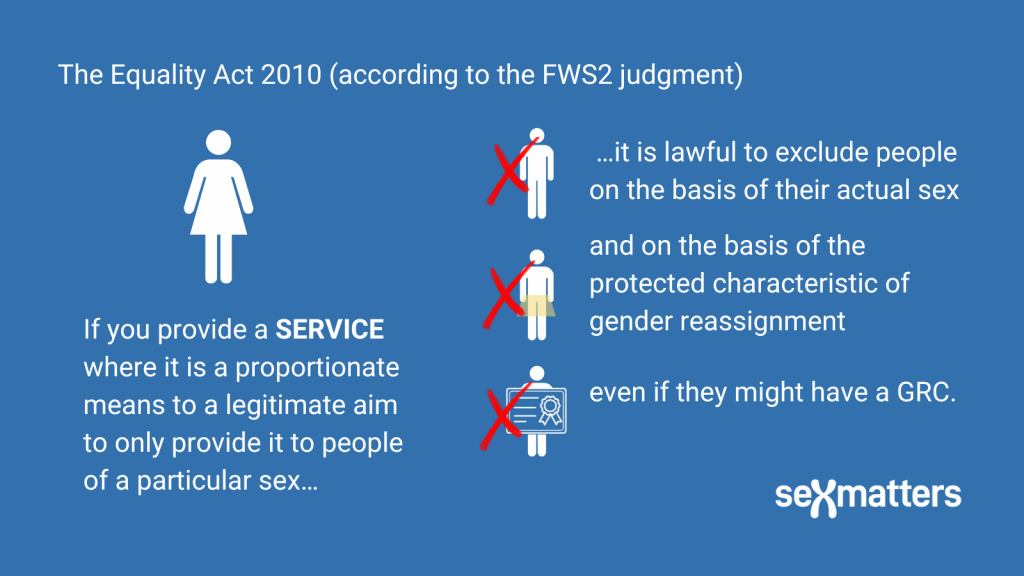

In these situations the Equality Act says that service providers are not subject to the legal prohibition against sex discrimination (defined as excluding someone or treating them less favourably because of their sex) or gender-reassignment discrimination (excluding someone or treating them less favourably because they are transgender or transsexual) as long as their policies and actions are a proportionate means to a legitimate aim.

These exceptions cover both dedicated single-sex services, such as a men’s homeless hostel, and facilities that are part of a larger mixed-sex service, such as the toilets at a cinema, or a weekly women’s swimming session.

Providing a service which you say is single-sex but where in practice women are forced to share unexpectedly with men could be sex discrimination (and also potential harassment). In the case of Earl Shilton Town Council v Miller [2023] it was found that single-sex facilities (in this case workplace toilets) were inadequate and amounted to sex discrimination, because of arrangements that in practice made them unexpectedly mixed-sex. A female staff member was put at risk of coming across men using an open urinal in what she was told would be a female-only space.

In order to provide any service, whether it is mixed-sex, single-sex or separate-sex, a service provider should communicate to staff and to customers who the service is for. This may be done with graphical and written signs, terms and conditions, policies, training to staff and communication between staff and customers. It should be done in language that all users can understand, and that can be communicated consistently and clearly.

What if someone has a GRC?

There is widespread uncertainty and confusion about whether people who identify as transgender, with or without a gender-recognition certificate (GRC) have the right to use services provided for members of the opposite sex.

Even among individuals who have a GRC there is disagreement about what (if any) rights it confers in relation to single-sex services.

- Anthony Halliday / Steven Hayden / Stephanie Hayden (has a GRC): “Nowhere within the GRA does it even begin to regulate access to such single sex facilities and services.“

- “Miss Gripper”, trans activist (has a GRC): “Yes I have a GRC I can use every female space”

- Cat Burton, Chair of GIRES (has a GRC): “The GRA is focused on the change of a single document, and that is all that this is really about. […] We are not trying to invade women’s spaces by getting a GRC.”

- Alex Sharpe, barrister (has a GRC): “I am trans woman; I have a gender recognition certificate, but I am still subject to the sex-based exceptions, if it can be shown that they are proportionate.”

The recent judgment in the For Women Scotland appeal in the Scottish Court of Session confirmed that a transgender person who does not have a GRC remains “of the sex assigned to them at birth and therefore would have no prima facie right to access services provided for members of the opposite sex”.

This simple situation covers the great majority of transgender people. According to the census 262,000 people in England and Wales identify as transgender (although this may well be an overestimate). Fewer than 6,000 people in the UK have a GRC.

If someone is excluded from a single-sex service because they are the wrong sex, that is sex discrimination. But it is not unlawful, because these services are permitted. So a service provider such as a gym would not be found liable for unlawful sex discrimination for having a policy excluding all males from a changing area and set of showers in order to provide privacy and security for female clients undressing there.

According to the For Women Scotland judgment, a GRC changes someone’s sex for the purposes of sex discrimination under the Equality Act. Although the judgment was not directly about the operation of single-sex services, it notes that the Equality Act also “entitles the service provider, subject to a proportionality test, to exclude a transsexual person” of either sex.

If the conditions for providing a single-sex service are met (such as that “the circumstances are such that a person of one sex might reasonably object to the presence of a person of the opposite sex”) this suggests it will also be proportionate to exclude a person who in reality is the opposite sex, but who has a GRC. This was the interpretation made by the Equality and Human Rights Commission in its guidance on single-sex services published in 2022.

What does the For Woman Scotland case mean for service providers?

Service providers can still continue to provide single-sex and separate-sex services.

It is good practice to have a clear, written policy so everyone knows whether a service is single-sex or mixed-sex, and so that the policy can be confidently justified. For example:

A gym decides to provide showers separately for men (male) and women (female) on the basis of the legitimate aim of maintaining privacy and dignity, and avoiding exposing women to an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment or enabling sexual harassment.

If a person who is male wishes to use the female showers, this would undermine the legitimate aim of privacy and dignity of the women using those facilities. This does not change because the biologically male person has a GRC, and in any case the exceptions allow for both sex discrimination and gender-reassignment discrimination.

The gym cannot practically or fairly decide to let some males into the female changing-rooms on the basis of “passing” or of having a GRC. It needs a policy that is clear and consistent, so that all users and staff can understand it.

The gym explains clearly on its website and in training for staff that the men’s changing-rooms and showers are for male gym users and the women’s changing-rooms and showers are for female gym users, and people cannot use the opposite-sex facilities, whatever their gender identity, even with a GRC.

It would be less discriminatory if the gym also provided a single-user unisex changing space with a shower, so that anyone who does not wish to use the male or female facilities according to their sex has somewhere they can change in privacy. But this may not always be possible.

There is no reason to ask to see a GRC

Service providers do not need to, and should not, ask for proof of possession of a gender-recognition certificate.

As the Equality and Human Rights Commission has said, in the guidance it published last year:

“You do not need personal information such as a Gender Recognition Certificate to make a decision. You only need to decide if your action is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. There is a risk of acting unlawfully whether the person has a Gender Recognition Certificate or not. The exceptions outlined in this guidance therefore do not depend on whether or not an individual has a Gender Recognition Certificate.

“A person does not need to have Gender Recognition Certificate to be protected under the characteristic of gender reassignment. You therefore should not ask for one when deciding whether to treat someone differently or exclude trans people from your service. Asking for one could also be a breach of someone’s right to privacy.”

If you are already providing single-sex or separate-sex services with a clear policy, you should keep calm and carry on. If you are running a lawful single-sex service, you already have good reasons to exclude people of the opposite sex from it. To avoid ambiguity you should make clear that this applies to all people of the opposite sex whether or not they have a GRC.

If you provide sex-separated facilities as part of a larger mixed-sex service (such as toilets at the cinema or changing rooms at the gym) you should also consider whether it is practical to provide a unisex alternative.

Because a GRC doesn’t make a difference to how the policy is enforced, you should not direct your staff to ask anyone if they have one, or ask to see it, but tell them to explain which services and spaces are open to people who are male or female and which are unisex, and train them on how to deal with conflicts or questions.

If your policy is unclear or ambiguous, or if you explicitly allow people to access sex-separated services on some basis other than their actual sex, you should review your policy.

What should the government do?

The government provides information to people who have a gender-recognition certificate, at the time of application. Currently this information states:

“Having a certificate means you can:

- update your birth or adoption certificate, if it was registered in the UK

- get married or form a civil partnership in your affirmed gender

- update your marriage or civil partnership certificate, if it was registered in the UK

- have your affirmed gender on your death certificate when you die.”

For the avoidance of doubt, we think this information should be added:

“Having a certificate does not:

• place any obligations on other private individuals to treat you as the opposite sex

• give you the right to enter spaces where services are lawfully provided as single-sex services for members of the opposite sex (your affirmed gender)

• give you the right to ignore directions by service providers relating your actual sex.

You should remain aware that other people have rights to freedom of belief and speech, bodily privacy and sexual consent which are not affected by your GRC status.”

If single-sex and separate-sex services can still be provided, what is the problem with the law?

The judgment in the For Women Scotland case may still be appealed further. But if it is the interpretation of the court that a gender-recognition certificate changes a person’s sex for the purposes of the Equality Act, this makes it legally more complicated to understand and explain why someone with a GRC is still not entitled to use opposite-sex services. This understandably makes service providers nervous. It also makes it harder to provide clear, simple guidance.

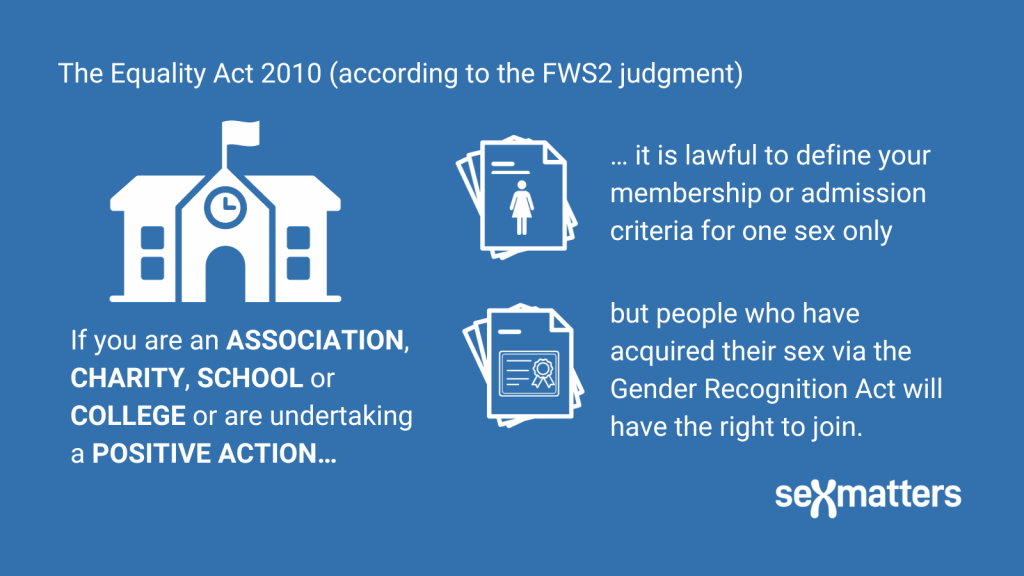

Defining “sex” as relating to certificates not bodies causes an even an even bigger problem for other areas of the Equality Act, including associations such as women’s organisations and lesbian and gay men’s organisations. In this case there is no separate exception to allow for gender-reassignment discrimination. We have written about this in our report Lesbians without liberty.

Nor is there an exception in relation to “positive action” programmes such as a women’s leadership course, or a women’s fiction prize. The result of the judgment is that it suggests that such programmes can only legally be provided on the basis of the protected characteristic of sex (including sex as modified by a gender-recognition certificate).

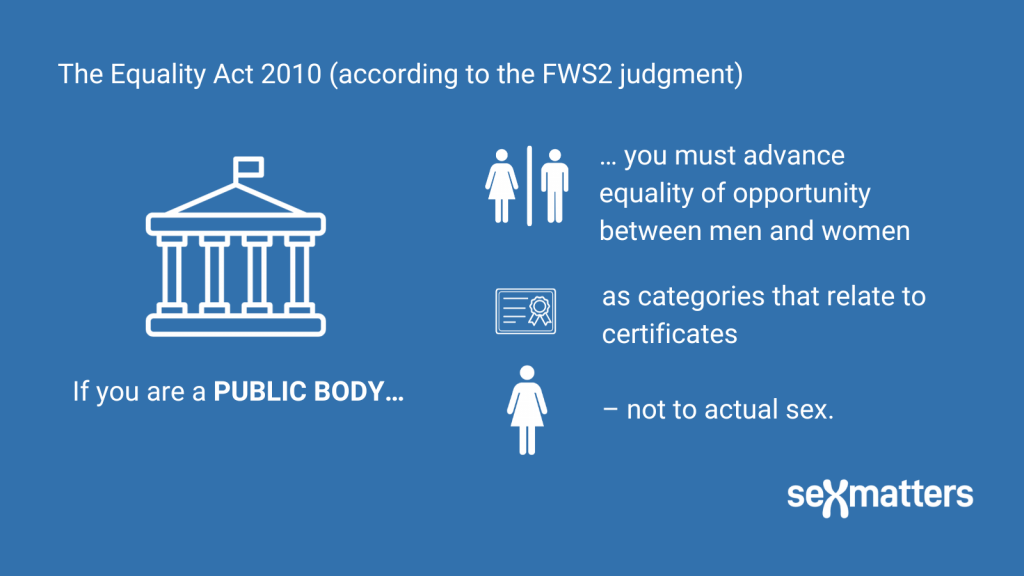

That interpretation also creates problems for the public sector equality duty. If “woman” in the Equality Act includes males with a certificate, then public bodies are not required to focus on advancing equality of opportunity between actual women and men, but only between people who are certified as women and men. This means that where there is a choice between different policies that are lawful, public bodies will not consider the interests of actual women as different from women-by-certificate.

This is why we are continuing to call for the government to amend the Equality Act to clarify that the protected characteristic of sex means actual sex, and is not modified by a gender-recognition certificate.