Data matters

How to collect personal data on sex and transgender identity

Advice on the questions you should ask when collecting personal data on sex and transgender identity.

See also our template letter of complaint to send when you are concerned that an organisation is misusing your data by confusing sex and gender.

Introduction

Organisations need to record information on the sex of individuals – whether they are male or female – for all sorts of everyday reasons, including getting the information needed to provide services fairly and safely, and to understand the characteristics and needs of populations. In recent years this routine question has become confused and fraught.1 Many organisations have been told that they should not record data on sex, but only on self-identified gender.2 This advice is wrong. Organisations can record and collect clear data on sex wherever it is needed.

This guide provides workable advice for organisations in the public, private and voluntary sectors, and for those setting data standards or providing templates to support others to collect data. It is intended to help you comply with:

- Data Protection Act and GDPR

- Equality Act 2010

- Human Rights Act 1998

- Gender Recognition Act 2004.

The best way to ensure data quality, avoid confusion, conflict and upset, and reduce the risk of liability, is to be clear about what information is needed, and why. Standard data-protection principles require you to ensure that information is:

- used fairly, lawfully and transparently

- used for specified, explicit purposes

- used in a way that is adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary

- accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date

- kept for no longer than is necessary

- handled in a way that ensures appropriate security, including protection against unlawful or unauthorised processing, access, loss, destruction or damage.

This guide applies these principles to the question of how to collect data on people’s sex and on whether they are transgender. It is intended in particular for data-protection officers and those responsible for data-protection compliance within organisations. But it will also be useful for anyone thinking about how to collect information on whether people are male or female.

Examples of collection of sex data

- Official statistics almost always include data on sex.3

- Employers are recommended by the Equality and Human Rights Commission to collect data on sex as part of their equality monitoring.4 Larger employers must publish data on the pay gap between male and female employees.

- Public-sector bodies have a responsibility to advance equal opportunities. Collecting data helps them understand the impact of their policies and practices on women and men.

- Schools are required to collect data on pupils’ sex.5

- Universities are required to provide data on students to Higher Education Statistics Agency. This includes information on sex.6

Definitions and concepts

Sex

Sex means being male or female. It is an objective, biological characteristic about a person that is observed at birth. Everyone has a biological sex and it does not change. This is recognised in law in the UK.7 Whether someone is male or female is usually readily observable and is not considered to be sensitive information. It is among the pieces of ordinary data (along with name, age, date of birth, national insurance number and so on) that an employer can hold without permission.8 Collecting data on sex is often legally required or officially recommended.

For clarity, sex is sometimes referred to as “sex recorded at birth”. But it is worth noting that around the world over 166 million children, mainly in the least developed countries, do not have birth-registration documents.9 Some people who come to the UK, particularly as refugees, did not have their sex officially recorded at birth. Their sex is no less certain because of a lack of a birth certificate.

A tiny number of people are born with variations in sex development that may cause their sex to be incorrectly recorded at birth (misrecording happens more often in developing countries). These individuals are still either female or male.

What about “gender”?

Gender can mean different things, so it is best avoided as a term in data collection. If you need to know about a person’s sex, that is what you should ask about.

People may say “gender” because they think the word “sex” sounds rude. For example, the “gender pay gap” is really the “sex pay gap”.

Some people use “gender” as a self-defined characteristic whereby someone male might identify as female or a woman, or vice versa (or as “non-binary” or some other identity). “Gender” is also used to refer to ideas about the differing social roles expected of men and women.

Some people believe that everyone has an inner “gender identity”, a “deeply felt internal and individual experience of gender”,10 and that when a person’s beliefs about their gender identity conflict with their sex, it is the gender identity that determines the person’s “true self”. This is not a concept that is recognised in UK law or defined by the UK government. In general, organisations should avoid asking questions about people’s deeply felt internal experiences unless they have a good reason to do so. They should be very careful how they store and use any such data.

Being transgender

Some people identify as “transgender” (or transsexual or trans). For example, a man may change his name and adopt feminine dress and hairstyle, and may take hormones or have surgery to make his body look less male. He may identify as a “transwoman” or “trans woman”. A woman may change her name and adopt masculine dress and hairstyle, and may take hormones or have surgery to make her body look less female. She may identify as a “transman” or “trans man”.

Other terms of self-identification include non-binary, agender, gender-fluid, gender-queer, androgyne, intergender, ambigender, polygender, transmasc and transfemme. All of these are self-declared designations. They have no legal basis and do not change a person’s sex.

People with a gender-recognition certificate

Around 5,000 transgender people in the UK have a gender-recognition certificate (GRC) which allows them to be recognised as the opposite sex for some legal purposes, such as marriage and pensions. They can get a new birth certificate which shows them as the opposite sex.

Getting a GRC does not require that someone has surgery, and does not mean that their actual sex has changed. For example, “transmen” who have not had their sex organs removed can get pregnant and give birth. Having a GRC does not change someone’s status as a mother or father.

The Gender Recognition Act 2004 provides that if someone has received a GRC, information about their actual sex becomes protected information. If you find yourself handling the information of someone you have learned in an official capacity has a GRC (for example, as their employer or as a service provider) you will need to comply with Section 22 of the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (for details on how to do this, see Appendix).

Sometimes the sex that is shown on a person’s birth certificate (which may have been reissued to reflect their GRC) is referred as “legal sex”. This is the sex variable that HM Revenue & Customs requires organisations to record for employees in relation to tax and pensions.

Sometimes organisations believe that they should only collect “legal sex” and not “biological sex”, or ask only about gender identity. This is not true. If you need information about people’s actual sex, that is what you should ask for.

Planning to collect information

Whether you are setting up a data system or making changes to an existing system, you should start by considering what information you need and why. It is good idea to document the purpose of the data, so you can justify its collection and use.

- Why do you want to collect data on people’s sex?

- Is it their actual sex you need to know, or their sex as modified by a gender-recognition certificate (GRC)? (These differ for only one person in every 10,000.)

- How accurate does the information need to be? (Does it matter if a small proportion of people give the wrong answer?)

- How complete does the information need to be? (Do you need to collect the information from everyone or can the question be voluntary?)

Common reasons for collecting and using information on sex

Information on people’s sex is needed for many purposes:

- because it is required by law – for example, schools must record pupils’ sex

- for healthcare and medical records –for correct diagnosis, screening, analysis of test results, treatments, dosages and so on

- for operational reasons – for example, where a person’s sex is relevant to their job (such as a bra fitter or women’s refuge worker) or where there are sex-based rules about who can access a particular service

- for sports – to decide on eligibility for competitions and to assess and record athletic performance

- for safeguarding – where an organisation places staff in positions of care towards children and vulnerable people

- for social statistics – for example, recording and analysing economic data by sex

- for equality monitoring – for example, to avoid sex discrimination in recruitment processes or to monitor workforces in order to spot patterns of discrimination

- in order to prevent, investigate or prosecute crime.

You may need to consider whether the information you want to collect is actual sex or sex as modified by a GRC. In almost all cases, if you are asking about sex it is actual sex that is the variable of interest.

What about identity-matching?

One common use of sex data is for identity-matching, for example asking for a person’s name, sex, and date of birth to match them with the correct record in a database.

In the past, matching a person’s appearance to their recorded sex was a routine part of checking whether individuals “owned” a unique identity (such as a bank account or passport). Someone with a male voice and a female name, or someone who looked like a man but had a female driving-licence number, might raise a red flag.

The use of sex data in this way has largely been superseded by technology such as PINs, fingerprints, voice recognition, iris scanning and automated facial recognition. It is rarely necessary to include sex as a variable in routine identity-matching. Using sex data or appearance for identity-matching in a situation where sex does not matter (such as at the bank) can cause embarrassment to transgender people. Try to avoid this by using other identity-verification methods.

There are situations where a person’s sex is needed for identity-matching, for example when searching for a missing person or criminal suspect.

Reasons for collecting information on whether people are transgender

You might also want to know whether individuals are transgender. Reasons include:

- equality monitoring

- providing specific services to transgender people

- carrying out research to understand the prevalence, characteristics and needs of transgender people.

Designing a question on sex

A simple question about sex

The easiest way to ask about sex is to ask a simple question and expect a straightforward answer.

![What is your sex? [radio button] Female [radio button] Male](https://sex-matters.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/What-is-your-sex.png)

You may not need to provide any further clarification. For 99.99% of people the answer will be the same whether they answer with their sex as observed at birth, or their sex as modified by a gender-recognition certificate (GRC). That may be accurate enough for your purposes. For example: a museum develops a questionnaire for visitors to collect statistics about the characteristics of its audience. It decides that the simple question is adequate.

For equality monitoring (which looks at anonymised patterns in data), this level of accuracy is likely to be adequate. The simple question without further clarification is the best option, as there is a live legal case about whether the protected characteristic “sex” in the Equality Act 2010 relates to a person’s actual sex or to their sex as modified by a GRC.11 A legislative proposal to clarify this question is also being considered by the government.

Questions with explanations

Sometimes it is important that everyone answers the question accurately. A person with a GRC needs to know whether to answer with the sex it says on their certificate or with their actual biological sex.

For social and medical statistics, accuracy can be important and even small numbers of misclassified cases can cause problems. Professor Alice Sullivan, Dr Kath Murray and Lisa Mackenzie point out that small numbers of people identifying as the opposite sex can have significant implications for research findings and for assessing policy interventions.12 These errors can make a big difference when the baseline category is small, such as for gay, lesbian and bisexual people. The Equality and Human Rights Commission says:

“When data are broken down by legal not biological sex, the result may seriously distort or impoverish our understanding of social and medical phenomena.”

Kishwer Falkner (2023). Letter to Kemi Badenoch.

Accurate classification is also crucial when it comes to healthcare. In the US a case was reported of a “man” who came into hospital with severe abdominal pains. The patient was in fact a pregnant woman, already in labour. Treatment was delayed and the baby was stillborn.13 The child might have been saved if it had been obvious from medical records that the patient was female. In the UK, NHS records do not accurately record a person’s sex14 – so it is possible that a similar tragedy could happen here.

In sport, too, it is actual sex, not sex as modified by a GRC, that matters.

For purposes that require data to be accurate for each individual, it is good practice to provide an explanation of what is being asked. This also allows you to record clear “metadata” – a description of the data that is stored alongside the records to help users understand them.15

For example:

- if you are collecting data for the purposes of tax and pension records, the information needed is “legally recorded” sex (which may be modified by a GRC).

- if you are collecting data for the purposes of an individual’s healthcare or for eligibility for sex-separated sports, the information needed is actual sex and accuracy is crucial.

For 99.99% of individuals these will be the same, and in practice hardly anyone will need the explanation. It can be footnoted with an asterisk, or placed behind a button on a computer form.

When you provide an explanation of the information being requested, this also allows you to get the data subject’s consent for using it. Even if they give the wrong answer, it has been made clear to them that they have been asked for their actual sex (and told why that information is needed), and that this is not a situation where they can expect their sex to be kept secret or lied about.

When you need to know about actual sex

![What is your sex? Please provide your sex, sometimes called sex registered at birth. [radio button] Female [radio button] Male](https://sex-matters.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/What-is-your-actual-sex-1024x272.png)

Use this question when you need to know people’s sex accurately, such as in medical and safeguarding settings, and where sex-based rules apply for the dignity and privacy of others.

When you need to know about sex as legally recorded

![What is your sex? Please provide the sex recorded on your birth certificate, or on a gender-recognition certificate issued by the UK government. [radio button] Female [radio button] Male](https://sex-matters.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/What-is-your-legal-sex-1024x309.png)

Use this question if you need to know an adult’s sex as legally recorded, such as for the purposes of tax and pension records and returns to HMRC.

Be aware that the sex shown on a person’s passport, driver’s licence or other records may not be accurate, as some organisations allow people to record their self-identified gender.

“Prefer not to say”

Depending on the context, you may decide that responding to the “sex” question is voluntary or to include a “prefer not to say” option. This will mean the data is incomplete, but people who do not wish their sex to be recorded in this context can simply opt out. For example, the UK Sports Councils Equality Group says:

“No individual is compelled to provide any information to a sports organisation. However, failure to provide such information would mean that person may not be able to compete in the category of their choice. Sports should provide options for those people who prefer not to advise of their sex or gender.”

Sports Councils Equality Group (2021). Guidance for Transgender Inclusion in Domestic Sport.

You should not offer either an “other” or an “intersex” option. The term “intersex” is used for people who have a difference of sex development (DSD) and they are, like everyone else, still male or female. Such personal medical information should not be requested except in healthcare settings or for rulings on eligibility for elite sports.

Ask clear questions

Organisations may be unsure whether they are legally allowed to ask about sex. They may worry that some people will feel uncomfortable or offended by such a question, or think that people would prefer to answer with their self-identified gender.

Such concerns make it tempting to frame questions about sex ambiguously. But this will produce poor-quality data, contravene data-protection principles and increase the risk of inaccurate data being used for decision-making where it matters.

![What is your gender? [radio button] Female [radio button] Male](https://sex-matters.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/What-is-your-gender-1024x256.png)

This question is ambiguous. Most people will understand it as asking for their sex, and will answer accordingly. But some will answer with their self-identified gender.

The Department for Education recently withdrew a data definition of “gender” and replaced it with one that states “sex”.16 The Higher Education Statistics Authority has also clarified that it collects data on sex, not “gender”.17

![Are you [radio button] Female [radio button] Male](https://sex-matters.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Are-you-female-or-male-1024x249.png)

Without any explanation of what the question is about, this question is ambiguous. Most people will understand it as asking for their sex, and will answer accordingly. But some will answer with their self-identified gender.

![Which of the following best describes you? [radio button] Female [radio button] Male](https://sex-matters.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Which-of-the-following-1024x236.png)

This question is ambiguous. Most people will understand it as asking for their sex, and will answer accordingly. But some will answer with their self-identified gender.

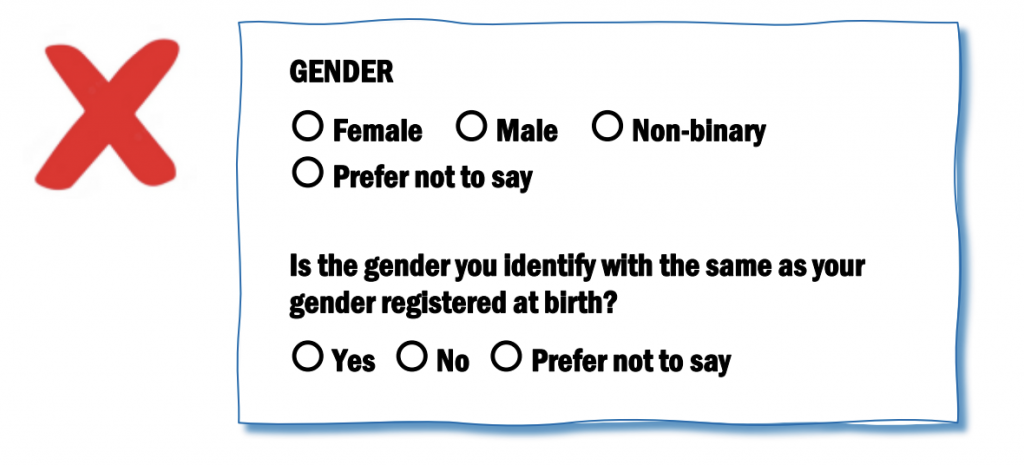

Don’t beat around the bush

Some organisations try to avoid asking the sex question altogether by asking a two-part question that starts with gender identity and then asks if this is the same as the “gender registered at birth”.

This is hard to understand and out of line with data-protection principles. It will yield poor-quality data.

In some cases, the answers to these two questions can be combined to work out what sex a person is. But this approach does not conform with data-protection principles. If you want to know and record what sex someone is, then that is what you should ask them.

Moreover, if someone answers “non-binary” to the first question, there will be no way to work out their actual sex. If they do not answer the second question or tick prefer not to say, their sex will also be uncertain, even though they may think that they have stated their sex by answering “male” or “female” to the first question.

Good practices

Apply ordinary data-protection principles

Be clear why you are collecting the data

Ask “What is your sex? Male or Female?”

Explain the terms if necessary

Consider a “Prefer not to say” option

Designing a question about transgender identity

If you want to know whether people have a transgender identity, you should ask this separately from the sex question. Responding should be voluntary.

Whether someone is transgender is sensitive data. You should ask about this only if you have a good reason and have considered the privacy implications of collecting the data. Your reason might be:

- operational – to identify transgender people as a population with specific needs

- statistical – because you want to know how many people identify as trans in a particular population

- for equality monitoring – “gender reassignment” is a protected characteristic and you may choose to monitor it (although you should consider whether this is possible in practice).

Appearing “inclusive” or wanting respondents to “feel seen” are not good enough reasons to collect data, especially sensitive data. Data-protection principles require that there is a lawful basis for collection, and that the information is used only for purposes that have been clearly specified in advance.

Should you include a transgender question in equality monitoring?

“Gender reassignment” is a protected characteristic in the Equality Act. However, this does not mean you must collect information on this characteristic. The small number of transgender individuals in the population means that data collected through routine equality monitoring is likely to be unusable as it would identify individuals, especially if it is broken down into categories such as job grade or work site.

The EHRC Employers’ Code of Practice states:

“Monitoring numbers of transsexual staff is a very sensitive area and opinion continues to be divided on this issue… If employers choose to monitor transsexual staff using their own systems, then privacy, confidentiality and anonymity should be paramount.”

Reflecting this, until recently the civil service did not monitor the protected characteristic of gender reassignment, but stated:

“Instead departments and agencies should consider other approaches, such as specific initiatives to meet different needs of transsexual people, in order to measure progress on trans equality.”

It did include questions in the anonymous Civil Service People Survey about whether “gender reassignment” or “perceived gender” was one of the possible causes of discrimination, bullying and harassment.18

Since 2016, Stonewall has promoted the collection of data on transgender identity.19 If you do decide to collect such information, we recommend that you treat it as special-category data (like sexual orientation and religion; see page 20).20 You should provide your data subject with sufficient information to understand how you are processing their special-category data and how long you will retain it for.

Questions about transgender status or gender identity should:

- be voluntary

- include details of how the information will be used

- allow analysis without compromising confidentiality

- never be mixed with data on sex – this will make the whole dataset both sensitive and ambiguous.

There is no standard way to ask people if they identify as transgender, and the recent census for England and Wales demonstrates a central difficulty.21 If non-trans people are asked whether their gender identity is the same as or different from their sex as registered at birth, the number who will be confused and will unintentionally indicate that they are transgender when they are not may overwhelm the data from the small number of people who genuinely identify as transgender. Your survey design should seek to avoid this. A simpler question is better.

If you are designing a question about trans identity, think about the age and background of respondents and make sure you are using language they will understand. Even if your colleagues are familiar with the terminology for transgender identities, your users are unlikely to be. This is a particular concern for people with learning difficulties or who speak English as a second language.

If you are asking about transgender status or gender identities as well as sex, aim to design your questions to make self-contradictory responses impossible (such as responding to a question about sex with “female” and a question about “gender identity” with “transwoman”). If this is impossible, decide in advance how such responses will be handled.

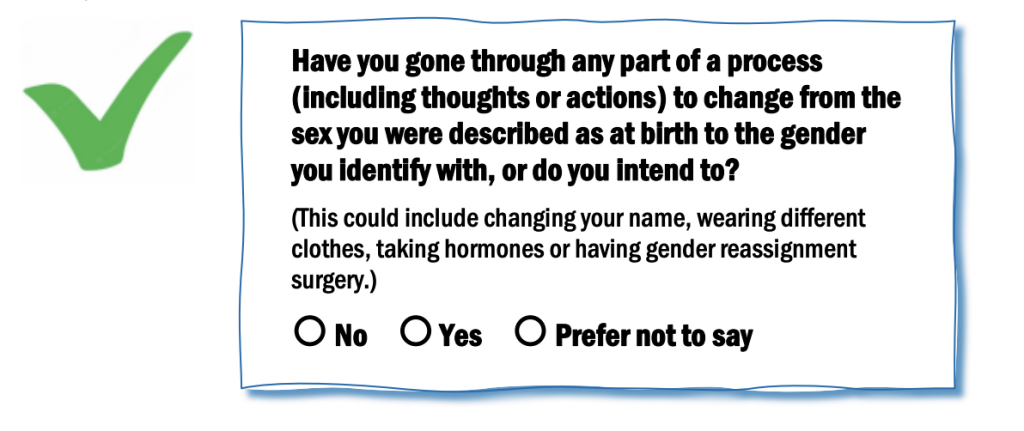

Some options for a transgender question

Questions about trans identity

The most straightforward approach is simply to ask if the respondent is trans.

![Are you transgender? [radio button] Yes [radio button] No [radio button] Prefer not to say](https://sex-matters.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Are-you-transgender-1024x287.png)

This question was developed by Advance HE for universities.22

This question was developed by Stonewall.23

![Are you trans or do you have a trans history? [radio button] Yes [radio button] No [radio button] Prefer not to say](https://sex-matters.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Trans-history-1024x305.png)

![Do you identify as trans? [radio button] Yes [radio button] No [radio button] Prefer not to say](https://sex-matters.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Identify-as-trans-1024x310.png)

For specific purposes such as research, you may wish to provide an additional field to find out what specific gender-identity term people use to describe themselves. But for equality monitoring, a yes/no answer is enough.

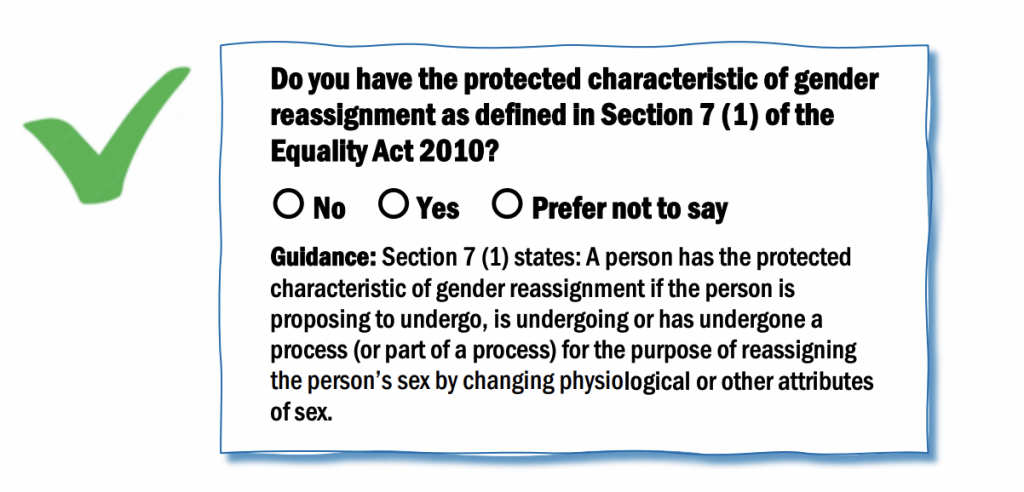

Questions that relate directly to the Equality Act

Some organisations have developed questions that directly relate to the definition of the protected characteristic of “gender reassignment” in the Equality Act. These are intended for the purposes of equality monitoring. But they are legalistic, difficult to understand and not widely used.

This question was developed by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (but the organisation itself does not use the question).24

This question was developed by the Social Market Foundation.

Bad practices

Asking about “gender identity” instead of sex

Mixing information from different categories

Collecting information on trans identity carelessly

Using appearance for identity matching

Corrupting your whole data set for “inclusion”

Appendix: Relevant legislation

Data protection

The UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provides the framework for lawful use of personal data.25 The Data Protection Act 2018 says that all personal data should be collected and processed following data-protection principles to make sure the information is:

- used fairly, lawfully and transparently

- used for specified, explicit purposes

- used in a way that is adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary

- accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date

- kept for no longer than is necessary

- handled in a way that ensures appropriate security, including protection against unlawful or unauthorised processing, access, loss, destruction or damage.

Special-category data

Under the UK GDPR and Data Protection Act 2018 some personal information is classed as special-category information and requires more stringent safeguards. Data on a person’s religion or belief and sexual orientation is classed as special-category. Data on their sex is not.26

The Information Commissioner’s Office says that information on a person’s transgender status or “gender identity” may involve special-category data, depending on the circumstances. This might arise if the information reveals specific details about the person’s health status or medical care, or an organisation uses it to make inferences about health (such as diagnosis of gender dysphoria, or surgery or treatment).27

Information that someone believes or does not believe in the idea of gender identity relates to beliefs, and is therefore likely to come under the definition of special-category data.

The ICO recommends:

“Organisations should be careful to think about fairness when handling [information about trans identification], and we would expect them to treat it with an appropriate level of sensitivity. They could decide to treat it as if it were special category data, to help them make sure they have a good reason for using it and comply with the fairness principle – although this isn’t an explicit requirement. This would mean they treat it in a similar way to other similarly sensitive data such as sexual orientation.”

Information Commissioner’s Office (2020). Policy on the handling of Gender Recognition Certificate cases.

The Equality Act 2010

The Equality Act requires that organisations do not discriminate against people, including workers, employees and customers, based on nine protected characteristics. These include sex and “gender reassignment”. Sex is defined as being male or female. Gender reassignment is defined in these terms:

“A person has the protected characteristic of gender reassignment if the person is proposing to undergo, is undergoing or has undergone a process (or part of a process) for the purpose of reassigning the person’s sex by changing physiological or other attributes of sex.

“A reference to a transsexual person is a reference to a person who has the protected characteristic of gender reassignment.”

Under the Public Sector Equality Duty, public bodies are required to eliminate unlawful discrimination, harassment and victimisation, advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations between those who share a protected characteristic and those who do not.

Public bodies covered by the specific equality duties are required to publish regular reports that include data relating to people who share a protected characteristic. Many organisations not covered by this also collect equality data to understand how they are doing. Large employers are required to publish “gender” (meaning sex) pay-gap data.

Equality monitoring is a lawful basis for collecting special-category data.28 But the information must be fit for that purpose and used only for that purpose. Employers and other organisations should therefore not include questions about transgender identity simply for the sake of being “inclusive” without thinking through whether they can analyse the data without compromising confidentiality. The small number of transgender people in the population can often make confidentiality impossible.

Organisations should consider whether they are undertaking indirect discrimination if they require users, staff or potential staff to answer mandatory personal questions about their gender identity, or questions which reveal their beliefs about gender identity.

It will not be unlawful indirect discrimination to have a mandatory sex question wherever this information is needed. Although some people with the protected characteristic of “gender reassignment” may feel that it is a detriment to them to be asked this question, as it makes them feel uncomfortable, asking it will be justified by the need to collect sex information for purposes such as equality monitoring, safeguarding and statistical analysis. People should not be excluded from accurate data collection about their sex because they have other protected characteristics.

Privacy and human rights

Article 8 of the Human Rights Act provides that:

- Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.

- There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

In general, managing personal data in line with data-protection principles will be consistent with respect for the human right to privacy.

Previous advice given by the Equality and Human Rights Commission stated that requesting, gathering and collating data on individuals’ biological sex could be in breach of Article 8 of the ECHR and the Human Rights Act 1998:

“Forcing trans employees or service users to disclose their sex as assigned at birth would be a potential violation of their human rights, particularly their right to privacy and dignity under Article 8.”

A legal opinion on this statement from Aidan O’Neill KC, commissioned by Woman’s Place UK, disagreed and noted that “privacy rights are not absolute and individuals do not have a universal veto on what can and cannot be asked of them”.

“Although the collation (and potentially the disclosure) of information and data about people’s private lives (which would include, details such as their name, age, sex, address, nationality, racial or ethnic origins, marital status, sexual orientation, sexual history, gender identity, health records, credit history, political affiliation, voting record, financial health, criminal record, whether charges and/or convictions) may be said to engage the rights protected by Article 8 ECHR, it will not constitute (unlawful) interference with those rights provided that the collation and/or disclosure is done in accordance with law and separately may be said to be “necessary” within the context of the proportionality test: that is to say that the collation and/or disclosure must involve the least interference with the right to respect for private and family life which is required for the achievement of the legitimate aim pursued.”

Woman’s Place UK (2020). ‘EHRC misrepresents the law on collecting sex data’.

The UK Sports Councils Equality Group advises sports governing bodies and sports organisations that they can collect data on sex:

“Categorisation by sex is lawful, and hence the requirement to request information relating to birth sex is appropriate.”

Sports Councils Equality Group (2021). Guidance for Transgender Inclusion in Domestic Sport.

The Gender Recognition Act

Around 0.01% of the population (around one person in 10,000) have a gender-recognition certificate (GRC). If someone has a GRC, information about their actual sex is covered by specific legal protections under Section 22 of the Gender Recognition Act 2004. This makes it a criminal act to reveal this information apart from where there are explicit exceptions.

Under Section 22 of the GRA it is a criminal offence for a person who has acquired protected information in an official capacity to disclose the information to any other person.

“Protected information” means:

- information that someone has made an application for a GRC

- information about the actual sex of a person who has a GRC.

A person acquires protected information in an official capacity if they get it:

- as a constable or the holder of any other public office

- as an employer, or prospective employer, or staff member of an employer

- in connection with their functions as a member of the civil service

- or in connection with:

- the functions of a local authority, public authority or voluntary organisation

- the conduct of business

- the supply of professional services.

This covers most forms of official and administrative data collection.

Exceptions to Section 22 of the Gender Recognition Act

It is not an offence under this section to disclose protected information relating to a person if:

- the information does not enable that person to be identified

- that person has agreed to the disclosure of the information

- the person by whom the disclosure is made does not know or believe a GRC has been issued.

Apart from where the information is used unwittingly, with consent or anonymously, there are specific and limited exceptions which allow for disclosure:29

- in accordance with an order of a court or tribunal

- for the purpose of instituting, or otherwise for the purposes of, proceedings before a court or tribunal

- for the purpose of preventing or investigating crime

- to the Registrar General for England and Wales, the Registrar General for Scotland or the Registrar General for Northern Ireland

- for the purposes of the social-security system or a pension scheme

- for purpose of obtaining legal advice

- in relation to organised religion (such as enabling any person to make a decision whether to officiate at or permit a marriage or in relation to employment, office or post, or membership of or participation in an aspect of organised religion)

- to a health professional, for medical purposes; and with a reasonable belief that the subject has given consent to the disclosure or cannot give such consent

- on behalf of a credit reference agency

- by an insolvency practitioner.

While the threat of a criminal penalty for disclosing information on a person’s sex is daunting, fewer than 0.01% of the population have a GRC, and there has never been a criminal prosecution using this part of the Gender Recognition Act since it became law.

The key risk that the GRA creates is that an organisation finds it has collected data on both on a person’s actual (“biological”) sex and their sex as modified by a GRC (such as for tax purposes), and linked these in a data system that many people have access to. With these two pieces of data, the fact that someone has a GRC may be either inferred or volunteered by the individual to explain the difference. This information, and the information about the person’s actual sex, then becomes protected information. Using it creates a risk of criminal liability for organisations.

This is a particular problem for large organisations that record sex as a part of a centralised “spine” of identity data on individuals. This information is likely to be widely accessible and used for many purposes. If it is possible to find out that a person has a GRC from their record in the data spine, this creates a risk across the organisation. At the same time, it can be crucial to be able to know people’s sex accurately in many situations.

To avoid legal risk, organisations typically do one of the following:

- collect biological sex as part of core personal data and ask for consent to disclose it as a condition of using the service

- collect biological sex and include a “prefer not to say” option so that those with a GRC can avoid giving information on their sex

- Collect legal sex on the main data spine (or don’t collect sex at all) and then confirm individuals’ biological sex when needed

- mark the records of people with a gender-recognition certificate as protected (put them in a locked filing cabinet or electronic equivalent).

Large organisations that mainly deal with people’s information rather than their bodies, such as the Department for Work and Pensions and the Information Commissioner’s Office, tend to take the protected records option. The Information Commissioner’s Office has a sophisticated policy for immediately isolating information that relates to a person with a GRC.30 The Department of Work and Pensions places the records of someone with a GRC in a special customer-records system.31

The NHS has taken the option of not recording biological sex accurately in its core data (even though this data is clearly needed for healthcare purposes and there is an explicit exception to Section 22 to allow health professionals to disclose a person’s sex for medical purposes). This decision has consequences right across the healthcare system. For example, radiographers must ask all patients, including patients whose medical records say male, for their “sex recorded at birth” in order to rule out the possibility of pregnancy.32

These elaborate (and flawed) systems cannot be replicated by every small organisation where sex matters. And in many of them, staff need to be able to have immediate and clear access to information on a person’s sex, which cannot be held in a locked filing cabinet or made unrecordable.

This means that in most cases when information will not be anonymised, it is safest to take the consent approach, that is, to explicitly collect information on biological sex and obtain consent for its disclosure for the range of purposes for which it is needed.33

Pros and cons of different approaches

| Approach | Pros | Cons |

| Collect actual sex and ask for consent | Organisation has accurate data on everyone’s sex that it can use for the purposes it needs | Difficulty in obtaining consent with a legacy system and existing data |

| Collect actual sex with consent and include a “prefer not to say” option | Data on sex remains accurateEasy for anyone who does not wish their sex to be recorded to opt out of having it recorded | A high rate of “prefer not to say” reduces quality for statistical purposes |

| Collect actual sex only as needed, and keep legal sex as the variable on the data spine | Sex for most people is accurate, and privacy for those with GRCs is maintained | Individual data is misleading where accurate sex data is needed on individuals (such as for healthcare or medical research purposes) |

| Mark the records of people with a GRC as protected | Privacy for those with GRCs is maintainedSex is recorded accurately for all | Protected records can make it difficult for people to access services easily |

This publication draws on guidance produced by the Information Commissioner’s Office, the Equality and Human Rights Commission, the Office for Statistics Regulation and Stonewall, and on Alan Henness’ Sex Not Gender project.

We are grateful to Professor Alice Sullivan, Alan Henness, Dr Michael Biggs, Naomi Cunningham and Tim Pitt-Payne KC for providing input and comments.

- Office for Statistics Regulation (2021). Draft Guidance: Collecting and reporting data about sex in official statistics.[↩]

- Woman’s Place UK (2020). ‘EHRC misrepresents the law on collecting sex data’.[↩]

- Office for Statistics Regulation (2021). Draft Guidance: Collecting and reporting data about sex in official statistics[↩]

- Equality and Human Rights Commission (2011). Employment: Statutory Code of Practice.[↩]

- Department for Education (2022). Data Operations – request for change form for CBDS RFC 1233.[↩]

- Higher Education Statistics Authority (2022). Definitions: Students. [↩]

- Corbett v Corbett [1971] pp 83, 104 D–G, 106 B–D and 107 A per Ormrod J; Bellinger v Bellinger [2003] UKHL 21, paragraphs 11–12 and 36–37 per Lord Nicholls, 56–57 and 62 per Lord Hope; Forstater v CGDE and others [2021] UKEAT/ 0105/20/JOJ.[↩]

- UK Government (accessed August 2023). ‘Personal data an employer can keep about an employee’.[↩]

- Unicef (2019). Despite significant increase in birth registration, a quarter of the world’s children remain ‘invisible’.[↩]

- Yogyakarta Principles (2006).[↩]

- Michael Foran (2023). ‘Equality Act and sex – important Scots cases on the horizon’. Scottish Legal News.[↩]

- Sullivan, Murray, Mackenzie (2023) ‘Why do we need data on sex?’. Sullivan et al. (ed.) Sex and Gender: A Contemporary Reader. Routledge.[↩]

- Marilynn Marchione (2023). ‘Nurse mistakes pregnant transgender man as obese. Then, the man births a stillborn baby’. USA Today News.[↩]

- Sex Matters (2022). ‘Appendix 1: Mapping the identity data corruption problem’. Sex and digital identities.[↩]

- Office for National Statistics (undated). Metadata policy.[↩]

- Department for Education (2022). Data Operations – request for change form for CBDS RFC 1233.[↩]

- Higher Education Statistics Authority (2022). Definitions: Students.[↩]

- Civil Service (2012). Best practice guidance on monitoring equality and diversity in employment.[↩]

- Stonewall (2016). Do ask, do tell.[↩]

- Information Commissioner’s Office (accessed August 2023). ‘What is special category data?’. Lawful basis.[↩]

- Sex Matters (2023). ‘What did we learn from the census?’; Michael Biggs (2023). ‘Why does the census say there are more trans people in Newham than Brighton?’. The Spectator; Michael Biggs. ‘Gender Identity in the 2021 Census of England and Wales: What Went Wrong?’. SocArXiv, 29th January 2023.[↩]

- Advance HE 2022. Guidance on the collection of diversity monitoring data.[↩]

- Stonewall 2016. Do ask, do tell.[↩]

- Equality and Human Rights Commission (2011). Monitoring equality: Developing a gender identity question.[↩]

- Information Commissioner’s Office (accessed August 2023). ‘What is personal data?’. Personal information – what is it?[↩]

- Information Commissioner’s Office (accessed August 2023). ‘Special category data’. Lawful basis.[↩]

- Information Commissioner’s Office 2020. Policy on the handling of Gender Recognition Certificate cases.[↩]

- Equality and Human Rights Commission (2010). Good equality practice for employers: equality policies, equality training and monitoring.[↩]

- See the Gender Recognition Act 2004 and the Gender Recognition (Disclosure of Information) (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) (No. 2) Order 2005.[↩]

- Information Commissioner’s Office (2020). Policy on the handling of Gender Recognition Certificate cases.[↩]

- R (on the application of C) (Appellant) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (Respondent) [2017] UKSC 72[↩]

- The Society of Radiographers (2021). Inclusive pregnancy status guidelines for ionising radiation: Diagnostic and therapeutic exposures.[↩]

- Information Commissioner’s Office (accessed August 2023). ‘What is valid consent?’[↩]