Clear rules and girls’ schools

Why the Girls’ Day School Trust’s single-sex policy is lawful and important.

In December 2021 the Girls’ Day School Trust (GDST) published a new Gender Identity policy. It is clear about the purpose of the organisation:

“The GDST was founded in 1872 with the purpose of giving girls an education they had been denied because of their sex.”

Sex Matters welcomes this policy, which makes clear that the schools remain single-sex. What’s more it says that GDST schools are:

“committed to rejecting gender stereotypes and associated narrow definitions of what it means to be a girl”.

It is significant, beyond the 25 girls‘ schools that the GDST runs, because it shows that a simple, clear approach can be adopted; and because it challenges the DfE and the regulators – the EHRC and the Charity Commission – to be similarly clear.

Is it lawful?

Some legal commentators have been quick to argue that this approach is unlawful, saying that the Equality Act 2010 requires girls‘ schools to consider individual applications from boys who identify as girls, and only refuse them on a case-by-case basis.

We think this is nonsense.

The law is straightforward: single-sex admission rules are expressly permitted in the Equality Act. A single-sex school is under no obligation to admit or consider admitting children of the opposite sex.

We have written a briefing, Clear rules and girls’ schools, that sets out the exceptions in the Equality Act that the GDST is using – for schools, for single-sex services, for charities and for sports – and why they are intended to work in exactly this way.

What about other charities?

One reason the GDST policy is so significant is that it contrasts with the approach taken by many other single-sex charities.

Charity trustees are legally obliged to continue to pursue the mission of the charity. GDST’s trustees are staying true to the single-sex mission established by its founders. But other charities with equally long-standing constitutions have not done the same thing.

Girlguiding has a Royal Charter that states that it is a membership organisation for women and girls. It hasn’t changed its charter, but now the website says:

“We treat trans girls and women according to the gender they have transitioned, or are proposing to transition, to. Meaning trans girls and trans women are welcome to be a part of our great charity.”

Girlguiding has expelled leaders who questioned this policy on safeguarding grounds. One example of a self identified woman in a leadership role at Girlguiding is Monica Sulley, who came to public attention after posting disturbing pictures on social media featuring weapons and bondage gear.

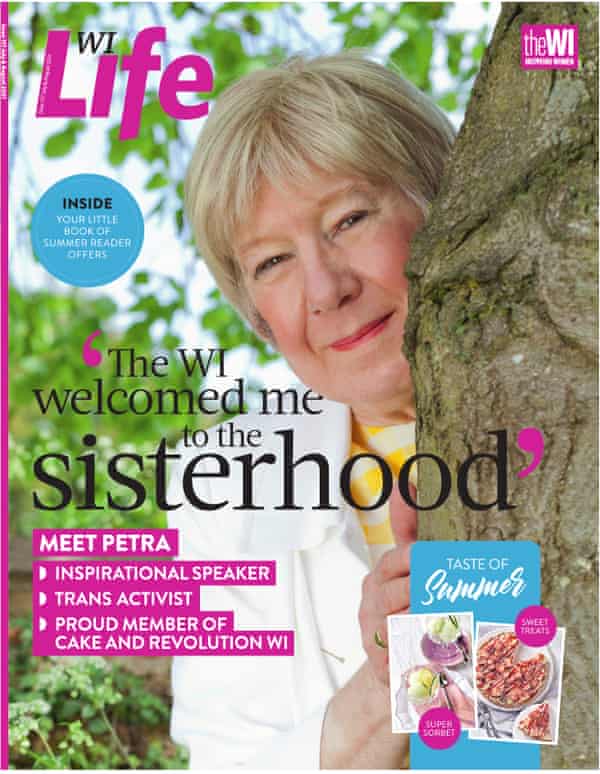

Similarly, the Women’s Institute says it is a single-sex organisation, using the Equality Act exceptions, and has not changed its charitable objects. But it says:

“Transgender women are welcome to join the WI and to participate in any WI activities in the same way as any other woman.”

Demonstrating this, the Women’s Institute in 2021 featured Petra Wenham on the cover of its magazine. Wenham is a married father and grandfather who lived for 70 years as a man before changing “full-time” to womanhood.

The case for coherence

Both of these organisations say they remain single-sex, and are using the single-sex exceptions in the Equality Act 2010. The Equality and Human Rights Commission and the Charity Commission have condoned their change of approach. The EHRC said in 2018:

“We have written to @girlguiding about their website but not to say they are a mixed-sex organisation. Like any membership organisation, the Equality Act allows Girl Guides UK to restrict membership on the basis of sex. We support their choice to have a trans-inclusive policy.”

In the recent Elan-Cane case over “X Passports”, the government argued for administrative coherence, saying:

“if a change is to be made it should be made coherently across the board or, if not, at least when the issues have been properly considered.”

The Charity Commission should also take an administratively coherent approach to determining whether a charity is pursuing its objects or serving a different group.

A coherent approach would be to say that if Girlguiding and the Women’s Institute want to depart from their historic female-only missions, and evolve into organisations for differently defined groups – people who share a belief in gender identity and who identify with the identity “woman” – they should have done so by changing their charitable objects.

What they have done instead is to reinterpret the words “women” and “girls” while pretending that nothing has changed.

Presumably they all thought that the doughty feminist founders of these organisations were out-of-date, bigoted dinosaurs whose vision could simply be ignored or overwritten for more enlightened times.

They were wrong. The EHRC and the Charity Commission should now explain to these charities that the definitions of the words “women” and “girls” in their charitable objects have not changed, and that as trustees their responsibility is either to pursue the charity’s original mission, or else to make the change official by consulting their members and adopting new constitutions.

Even more fundamentally, all organisations must remember that the words “boys” and “girls”, “men” and “women” are not just words on a page, or strongly held feelings or identities. Nor are they just equality categories. They are physical realities with associated vulnerabilities.

Girls and women can become pregnant. One in four women have experienced sexual assault. Fully 98 per cent of perpetrators are male.

Safeguarding practices and single-sex facilities are designed to prevent and deter abuse, including grooming through keeping secrets and eroding boundaries; and opportunistic voyeurism or indecent exposure. You cannot safeguard children and teach them about consent if you do not have a culture of honesty and clear rules.

And you can’t do this if you allow the words and concepts for the two sexes to become confused and seen as offensive, or turn a blind eye when rules are broken.

People must be free to express themselves however they want in their private lives, but when it comes to rules and laws that protect everybody‘s rights, the words related to the two sexes must be allowed to have stable, consistent meanings, for fairness and coherence and for safeguarding.

The organisations that sit at the top of those regulatory hierarchies have a basic responsibility to maintain that clarity. The DfE and EHRC should issue clear guidance to schools, and the Charity Commission should explain to single-sex charities that sex still means what it meant when they were founded.