Interview with Maya Forstater

Sex Matters’ Executive Director Maya Forstater won an important judgment in 2021 in her employment discrimination case. Now she is going back to court. Before her hearing begins next week on 7th March, Sex Matters interviewed Maya about her journey.

Maya Forstater’s case has already been celebrated as a breakthrough for protecting freedom of belief and sex-based rights in the UK after she won in a judgment from the Employment Appeal Tribunal, overturning the previous decision that her views were not protected under the Equality Act 2010 because they were “incompatible with human dignity and fundamental rights of others”.

The Appeal Tribunal ruled that “becoming the acquired gender ‘for all purposes’ within the meaning of GRA [the Gender Recognition Act] does not negate a person’s right to believe, like the Claimant, that as a matter of biology a trans person is still their natal sex”. She is about to return to an employment tribunal to bring the claim that she was discriminated against by her employer because of her protected belief (and you can still support her crowdfunder).

How long has it taken to prepare for this next court case?

I cannot count the hours! It will have been three years to the day from when I lost my job to when the final case will start to be heard.

Partly it was slowed down by COVID of course, which affected everyone. It has been lots of waiting, punctuated by months of intensive work by my legal team putting together the evidence bundles, and legal arguments at each stage. For this final stage we started really getting ready in autumn last year. I had to go through all my emails and tweets and documents and write my witness statement. And then you get the disclosures from the other side: you see all the emails you couldn’t see at the time. It’s quite an upsetting process, dredging up an awful time in my life, when I was isolated and trying to save my job.

My legal team have built a chronology which puts it all together, and then the legal arguments which have to address both the question of my employment status and the discrimination. I hope that when the tribunal hears how I was treated they will see it as a clear case of discrimination because of my belief.

Is this another example of the process being the punishment?

Definitely. I wouldn’t recommend anyone go into this process unless they have to. The worry and stress of it takes over your life. And it has taken over my public profile. I didn’t imagine it would go on so long when we started it, but I’ve just kept putting one foot in front of the other. You can’t move on till it’s done.

My case has been crowdfunded, otherwise I couldn’t have done it. I’m hugely grateful to everyone who has supported it. Hopefully my case is leading the way so that employers start to realise that staff who don’t believe in gender ideology have rights. And people who do get into disputes with their employer can use my precedent.

This case must have created a huge upheaval in your life?

I feel as if we’ve all been in suspended animation. My case created this huge upheaval for me, and then the pandemic changed everyone’s lives. It’s hard to think of what life was like before. And then, obviously, there was J K Rowling. Her tweet after I lost turned my world upside down for a bit.

I miss people. I’ve lost a few friends, and made many. But it can be awkward in new social settings when people ask “What do you do?” and I have to tell my story. You never know who in a group will say “I’m behind you” and who is going to look at you like something awful.

I still have to remind myself how bizarre this all is – to go through all this for saying something so banal as there are two sexes. You can get used to anything, and you get used to thinking you are a social outcast. It’s not healthy.

Have you had to become a legal expert?

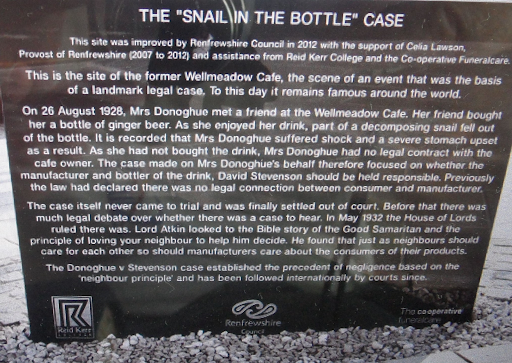

Naomi [Cunningham] tells me I’m like a snail in a bottle. There is this case, Donoghue v. Stevenson, that lawyers all know about. Someone in Scotland in the 1920s got sick after drinking a bottle of ginger beer with a decomposing snail in it. They sued the business that made the drink and that ruling established the civil law tort of negligence and obliged businesses to observe a duty of care towards their customers.

So I’m like a talking snail. There is this bit of law that relates to me. And here I am!

I feel like I know quite a lot about being a claimant, and I’ve ended up giving advice to people starting their own cases and crowdfunders. One piece of advice I pass on was given to me by James Farrar before I started – he is an old friend and is one of the claimants in the Uber case (about employment law, nothing to do with gender). He said “Enjoy it” and I think that is good advice. It’s the only way to keep going.

I’ve become fairly expert on the Grainger criteria (belief discrimination) and also on the single-sex and separate-sex exceptions in the Equality Act, and the legal definition of sex. The single-sex exceptions don’t really relate to my case at all, except that I wanted to talk about how they work.

There is lots of esoteric law about sex and disputes in court like the recent cases in Scotland brought by Fair Play for Women and For Women Scotland – the law makers really did not think through what the impact of allowing people to change their sex “for all purposes” would be. I’ve got quite good at following the legal arguments, but you shouldn’t have to. This stuff about sex should be simple.

We all know what sex is, and what sex we are, and that people can’t change sex. That’s reality. Organisations can’t function if they can’t talk about reality. They can’t treat people fairly if they try to pretend that it’s more complicated than that.

The judge at the first hearing brought up your dispute with the Scouts Association – did that seem fair?

Well, anything that is in the evidence bundle is fair game. Because the first part of my case was about my belief, I had to disclose everything I had written about my belief at that point, even though it didn’t directly relate to my job. So I had to put in letters to my MP and the dispute with the Scouts.

I was a Scout Leader so I had written to them about safeguarding, and I went and had a meeting with some of the staff from headquarters. Then when they updated and improved their policy, I wrote an article for Transgender Trend. That kicked off an argument with Gregor Murray – this person I’d never met who prefers to be called “they” and doesn’t identify as a man. I forgot not to say “he”. Murray complained about me to the Scouts for that. The Scout Association took it seriously and it dragged on for over two years with several investigations.

The judge in the first tribunal, James Tayler, quoted the Equal Treatment Bench Book. This is guidance for judges, which is completely untransparent and unaccountable. We don’t know who wrote it, and it wasn’t put to me during the hearing. [More details about this at Maya’s own website.]

The judgement got stuck on the idea of me “misgendering” people. The only example in the evidence was that I called Gregor Murray “he” on Twitter.

In the employment appeal tribunal, the incident with Murray came up again. Ben Cooper, my QC, was talking a mile a minute and he noticeably slowed up with the effort not to “misgender” this person. This is the Stroop effect. And I could see the Judge, Akhlaq Choudhury, looking at the newspaper article about Murray we had in the bundle, just staring at it for a good long while.

Eventually at the end of last year, the Scout Association finally apologised for what they’d put me through with Murray’s complaint. I miss being a Scout Leader, but that is another part of my life I can’t get back.

Some critics claim that you didn’t lose your job but simply didn’t have a freelance contract renewed – could you clarify what happened?

The details of this are something for the tribunal to consider. But basically the Equality Act 2010 protects you as an employee or anyone with an agreement personally to perform work for an employer (if they are not doing so as a self-employed professional providing services to a client or customer), as well as ex-employees and people seeking employment. You shouldn’t be discriminated against or harassed in any of those situations. I’m always surprised that people who think they are progressive make this anti-worker argument.

So the fact that I was not a regular employee on a PAYE contract who was given a P45 but was part of the “gig economy” doesn’t mean that I have no employment rights (thankfully). I had a job, which I was good at, and an expectation of continued employment, and career prospects. And then I didn’t. I was investigated because I’d tweeted about sex and gender, and all of that was taken away from me. I’d call that discrimination. Hopefully the tribunal will agree.

It seems odd that what seems like simple scientific fact – the reality of biological sex, which is how humans reproduce – was described as a “belief”.

The piece of case law that defines a philosophical belief for the purpose of the Equality Act is Grainger v Nicholson – it’s about climate change. Mr Nicholson’s belief was that climate change is real and that it is urgent and important to act on it. That doesn’t mean that climate change is any less of a scientific fact, but his belief was about its personal importance.

Mr Nicholson’s whole belief was found to be coherent, weighty, and “worthy of respect in a democratic society” (which means not destroying others’ rights).

Similarly, my whole belief is not just that sex is real, binary and immutable (the science), but also that it is important this is recognised and we can talk about it, and protect rights based on it. What came into question is whether that destroys others’ rights. The Employment Appeal Tribunal said it did not. Making the argument about “belief” might seem strange, but it was the one that was open to us in the Equality Act.

Perhaps more important than the finding on “belief” was the finding on “lack of belief”. We pleaded both that my philosophical belief is protected and so is the belief of people who think gender identity is important. We had to prove that this was a coherent belief system. I remember reading Judith Butler looking for something to put in the evidence bundle to show coherence – I gave up on that one.

If belief in gender ideology is protected, so are the rights of people who don’t share it: it’s like being a “gender atheist”. This is important because it means you don’t have to have paid attention to the debates to have protection. Your grandma who knows (and is disturbed) that the person in the hospital bed next to her, who the nurses say is a woman when she can see they are male, is protected, even if she’s never thought about queer theory.

And the “belief” framework is helpful for organisations to find a way to deal with the debate, and to protect everyone. We already know how to live in a plural society where Muslims, Christians, Jews and atheists live and work alongside each other and get along. We know how to respect freedom of belief.

The first judgment seemed completely crazy: it read like a character assassination. What was your reaction at the time?

It was awful. The judgment took parts of tweets of mine and quotes out of context and patched them together to shore up the conclusion that I had (or would) create a hostile workplace by harassing people. It was like a Twitter hatchet job, and that’s because it drew from one.

One of the weirdest parts of the first hearing was that CGD called a surprising witness: a Marxist tax lawyer I had been acquainted with as David Quentin, but who now goes by the name of Clair.

Quentin is a person I had met at conferences a couple of times (as David) and had had disagreements with about international tax policy (the topic I worked on at CGD). Quentin was now non-binary, and had taken against me when I published my first essay on sex and gender; when I launched my case publicly, Quentin started tweeting diatribes against me saying I caused harm, and telling our mutual followers not to associate with me professionally.

So when we received that witness statement I put Quentin’s tweet threads about me into the bundle to show the bullying. It was those tweet threads with screenshots of my tweets that James Tayler quoted from. The only trans person involved in the tribunal was Kristina Harrison, who spoke up for me.

How soon did you decide to appeal the decision?

I think straight away, but those few weeks after the judgment are a bit of a blur.

There were some blistering rebuttals of that original judgment from feminists such as Jane Clare Jones and Kathleen Stock. Did that make a difference to you?

Yes – it was great that people wrote about it, and I collected all the analysis on my website. I worked for a think tank and I felt very strongly that I had a duty to talk about this issue because there is a massive hole where the rational analysis should be. And people who do the rational analysis like Kathleen Stock get punished and driven out of academia. That’s why I started tweeting. That was the difference I wanted to make.

So I was really pleased that my case led to people writing about the issue and grappling with it seriously. And not just confirmed supporters. Karon Monaghan QC wrote an excellent analysis of why the judgment was wrong, early on. She is a hugely well respected equality lawyer. And Professor Robert Wintemute, a human rights law professor, wrote an article. He was one of the original signatories of the Yogyakarta principles, and he has realised they got it wrong. That was pretty significant. He submitted the article to the Human Rights Law Review, whose editor Jonathan Cooper had already published an article by a sociologist arguing that James Tayler got it right, and it was refused. Eventually it was published by the Industrial Law Journal.

Whose support in this has surprised you most? Whose opposition?

I’ve been continually disappointed by how much my previous colleagues in the development and think-tank world have pretended this wasn’t happening. These are people who work on human rights and “open government”, and if nothing else I am an interesting case study.

But no-one has written anything serious either for or against me. I have had a few people speak privately with me, and I really appreciate that. It is one thing to be loved and hated by thousands of strangers, but it’s another to be cancelled by people who know you.

There are several men who have stood up for me. My husband, who has had the worst time in all of this. My sons. My dad who came to my tribunal every day. My long-time colleague and mentor Simon Zadek (who really spoiled me in life because I had such a good first boss I thought everyone would be like that). And Owen Barder. Owen was the CEO at CGD Europe but was on his way out when I was being investigated. He disagrees with me on the issue, but he defended my right to speak. He has taken it upon himself over the past three years to try to slay the internet myth that I harassed a trans colleague.

How much difference did it make having J K Rowling’s support? Were you a fan of hers before that point?

My sons are 18 and 22, so we had read all the Harry Potter books together when they were young. We’ve watched the films many times. We have a lot of Lego sets. I’ve been to Harry Potter World. She was definitely part of our lives.

It was amazing when she tweeted about my case.

It came out of the blue, and it made my case internationally famous for a while. I had journalists turning up at my door. And every time she tweeted about the issue it set off a Twitter storm about me, with people trying to discredit her and me. That has been tough, but it brought more attention to the case, and the injustice of it.

I am grateful she spoke up for me and that she has been so brave and solid in writing about the issue and not backing down.

I do wonder how much she knew about me when she tweeted. How did she know whether I could cope with the attention she was about to send in my direction? She must have known what she was doing because I’ve been all right.

You’re about to go back to court for a third time: can you explain why?

Critics say this is a re-hearing of the original employment tribunal, but that is a misunderstanding. This is the first time the full facts of my case will be heard: how I was employed, what people were offended by, how I was investigated, how I lost my job.

The appeal decision in my favour means that gender-critical people are in the same position as people with religious beliefs: our freedom of belief and freedom of speech are protected. But that is not absolute. Employers can of course restrict speech where it is necessary to do the job. They can also determine that manifesting some beliefs is incompatible with doing a job.

There is a case called Ladele about a Christian woman who was a registrar. She didn’t believe in gay marriage, and that belief was protected. But after gay marriage was brought in her employer said she could not be excused from conducting these weddings. Her belief was found to be incompatible with doing the job. Another case is Ngole. He was a social work student who expressed the same Christian belief on Facebook. It was found that this was not incompatible with doing his job.

So exploring the boundaries of protection for the manifestation of beliefs in practice is just as important as having the right in principle.

What will be the implications of this case if you win?

The internet myth about my judgment is that “the belief is protected but not the manifestation” – the idea is that you can believe what you like about sex and gender, but if you let that thought escape your head then you deserve to lose your job.

This is a wilful misreading, but is surprisingly popular with HR departments that still haven’t got to grips with the idea that enforcing gender ideology is belief discrimination.

If I win, HR departments will have to pay attention, and recognise that adopting gender ideology and enforcing its mantras creates a risk of legal liability. Employers will have to stop blithely adopting policies that amount to bulk discrimination against the people they label as TERFs and bigots.

And if you lose?

It depends what I lose on. I’ll have to talk to my lawyers.

What good things have come out of all this?

Sex Matters! And good people. I’ve met brilliant, brave people.

And I’ve made a difference. It really started to come home to me towards the end of last year when we started to go out to events again. I went to an event in Cambridge and one in Oxford, and the FILIA and LGB Alliance conferences, and everywhere I went I met people who said my case had changed things for the better for them at work.

There are very few Forstaters in the world, and “Forstater” is now this precedent that protects people at work. I’m proud of that.

How did Sex Matters begin?

I started talking about it with Anya Palmer, my barrister in 2020. I had come to the point where my case, and J K Rowling’s intervention in it, meant my life would not ever go back to normal.

Anya was Stonewall’s second employee in the days when they were a scrappy small organisation fighting for gay rights, and we talked about Stonewall’s early strategy and tactics, and the kind of organisation now needed.

LGB Alliance had just got started. They are great, and hugely needed. But I’m straight, and so are many of the people affected by this ideology. There is an amazing constellation of grassroots micro-organisations in the UK fighting gender ideology from different perspectives: feminists, parents, left and right. I felt there needed to be an organisation which is for everyone, and which focuses on the basics: sex is real, and the freedom to say that underpins everything else.

Anya came up with the name “Sex Matters”, but looking back I can see it is a phrase I used in my first witness statement. We set up Sex Matters as a not-for-profit company with Rebecca Bull, a solicitor. Then Dr Emma Hilton, who is brilliant, joined, and Naomi Cunningham, another barrister, became Chair of the organisation. Professor Michael Biggs also joined the board. Halo Garrity (amazing coordinator and circus performer) is our second employee.

Sex Matters got a little bit of seed funding from some angry city women and we set up the website.

We have a small team and every step is learning. We have become clearer about what the organisation is: we are a human rights campaign. We are taking and making the space that established organisations have ceded, to try to bring calm debate, understanding and solutions.

How did your area of expertise feed into Sex Matters?

I’m a policy wonk, a researcher, writer and campaigner. I’ve worked on business and human rights, supply chain labour standards, climate change finance and international tax. They are all subjects with real conflict and deeply entrenched positions and battles where progress has been made when people come out of the trenches, look each other in the eyes and start to find common language, and focus on their interests not their positions.

That’s what I’ve worked on all my life, so I’ve turned it to this.

I’ve worked in NGOs and think tanks, with big business, with charities, with government departments and with the United Nations, but I’ve always been an outsider; I think that helps here. Ultimately I think this is all about organisations: how do we turn them back to their missions? How do we get their leaders to realise just how corrosive this ideology is to their culture? How do we make it safe for people inside organisations to hold their nerve and speak up?

Outside gender-critical circles, do you find that people have heard of you and your case?

I’ve been stopped in the street a few times (always nicely) and I’ve had a few teenagers glare at me in the street. But only if I have my hair down and a “Woman” hoodie on. That makes me quite recognisable to people who’ve followed the story. Otherwise I am just another invisible middle-aged woman.

Quite a lot of people have heard of the story in relation to J K Rowling. But often they don’t know much else. The effect of the silencing and cancellation is that people are afraid to approach the topic. They can see that it’s dangerous. It is more trouble than it’s worth.

Busting out of that silo, making it clear and easy and safe to talk about this; that’s what Sex Matters has to do to succeed. And if I win my case it will be a major step forward.

Support Maya’s crowdfunder at https://www.crowdjustice.com/case/stand-with-maya