Hadley Freeman interviewed on Woman’s Hour

On 5th December 2022, Hadley Freeman was interviewed by Emma Burnett on BBC Woman’s Hour. She talked about why she was leaving the Guardian, after 22 years of working for the paper.

The audio with subtitles available on Youtube. We have added links to relevant media articles, and to Hadley’s music choice.

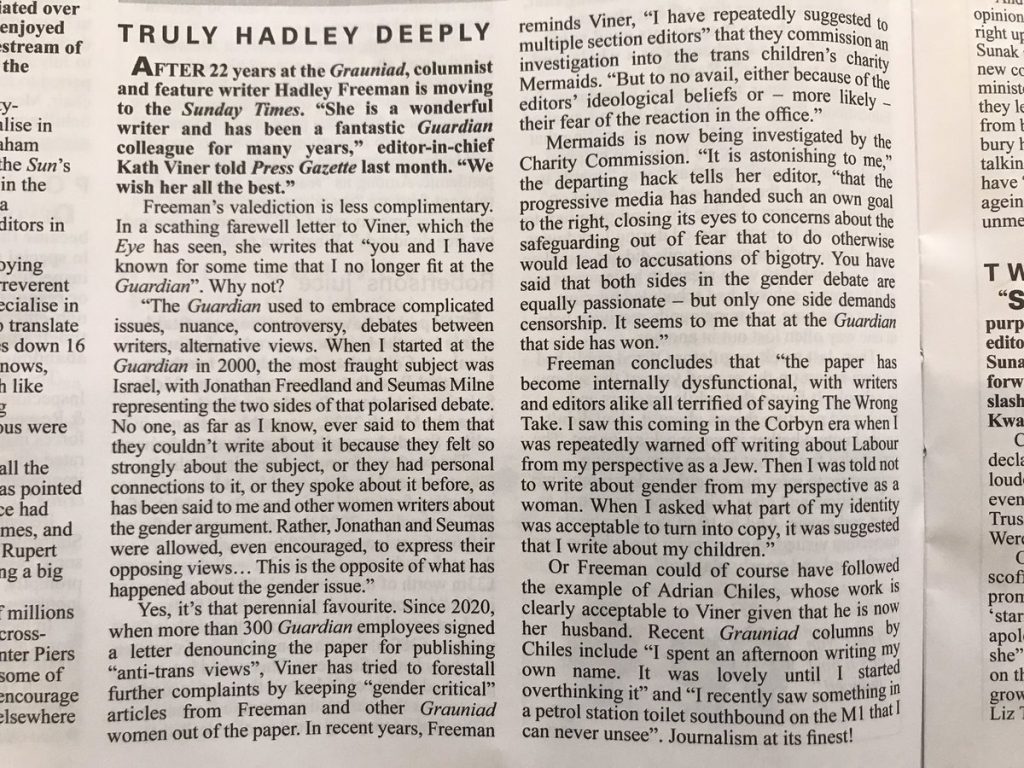

Emma Barnett: Six weeks ago, my first guest resigned from the Guardian, a newspaper she has loved and worked for for 22 years, most of her working life. The reason? She claims she was censored about writing on the Labour Party during the Jeremy Corbyn era, from her perspective, in part as a Jew, and then again about writing about gender and trans issues from her perspective as a woman – both claims the Guardian paper denies. Her resignation has sparked considerable debate in the media world after extracts of her resignation letter to the newspaper’s editor, Katharine Viner, whom we’ve also invited onto the programme, were leaked and have appeared in Private Eye.

Hadley Freeman is who I’m talking about. She’s worked as a staff writer as I say for a long time. 22 years at the Guardian, but joins the Sunday Times in January. And is also an author – she’s finishing a book at the moment on girls and anorexia, which comes out next year. Hadley Freeman’s just joined me in the studio. Good morning.

Hadley Freeman: Hi, Emma.

Emma Barnett: Why did you resign when you did?

Hadley Freeman: Well, as you say, I’d been at the Guardian for a long time and it felt like I’d been in a very happy long-term marriage for 15 years. And then about seven years ago, that particular partner started to become a conspiracy theorist, to be honest, and unrecognisable to me and it just got to a point where I couldn’t take any more. And this specific conspiracy I’m referring to is, of course, the gender-identity or gender-theory idea, and the censorship of women writing on it. And the thing that finally pushed me over the edge was, I’ve been asking editors across the paper for over six years if I could write, or someone could write, a long piece about Mermaids and Susie Green, the charity that claims to support what it calls “gender non-conforming children”. And I was always, always told no, but the reasons always changed, it was you know, this isn’t the right time. or we don’t see the interest, etc, etc. Even when Mermaids was given 500 grand by the National Lottery I was still told no there’s no news peg, and I pitched again in August to an editor and they said no, it’s not relevant or something.

And then in September, the Daily Telegraph ran a big exposé about Mermaids and it led to the Charity Commission saying they were going to look into it.

And I asked the news desk, you know, are you going to follow up on this? And they told me, no, we don’t follow other people’s stories. And I just thought, so you’re not going to commission me to do anything, or anyone, not necessarily a news report, it didn’t have to be me, and you also won’t follow other people’s reporting on it. Like, I don’t understand. And at that point, I thought, Okay, it’s time to go.

Emma Barnett: I should say on Friday evening, on that point about Mermaids, the Charity Commission has escalated its investigations into Mermaids, announcing it’s responding to newly identified issues about the governance and management of the transgender children’s charity. Hadley, to come to your points, there’s a few in there, you are saying that you specifically were not allowed to write by this. Are you saying others were and you weren’t?

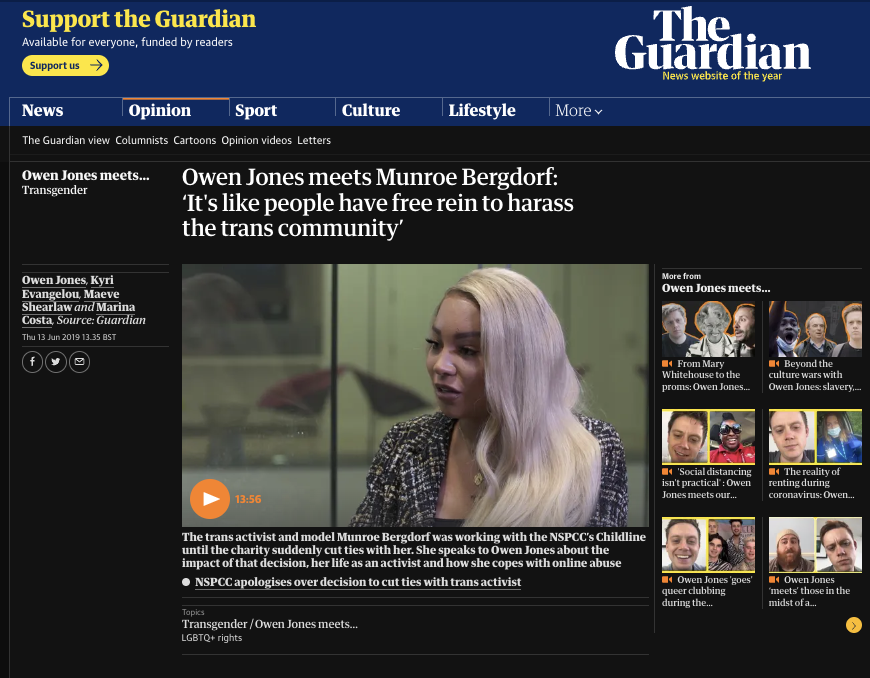

Hadley Freeman: No, I was specifically not allowed, I was specifically told by upper management that I wasn’t allowed to write about gender stuff in about 2018, 2019 I think, and others weren’t either. I know of multiple reporters who asked if they could interview for example, Maya Forstater, during her case, Allison Bailey, Jess de Wahls, I asked about interviewing JK Rowling, and Martina Navratilova, and we were all told no. Meanwhile, you know, the paper ran these long, glowing profiles of trans activists such as Munroe Bergdorf, and Paris Lees, and Freddy McConnell, and I’m proud to have worked at a paper that spotlit marginalised people like that. I just don’t understand – well, I do understand but it infuriated me – that feminist campaigners such as Julie Bindel, who I also pitched to interview, when her book came out, and JK Rowling were basically shut out from the paper.

Emma Barnett: When you go on the Guardian’s website, there are interviews with those who are described as having so-called – some people don’t even agree with this way of describing it, but if we could use this phrase for a moment – gender-critical views, such as Kathleen Stock, who I remember interviewing here on the programme, after she was put in a position that she said she felt she had to leave Sussex University, and Maya Forstater who we talked about who won that particular case; they’re on the Guardian website, but are they under the Observer?

Hadley Freeman: I believe Maya Forstater was interviewed in the Observer – I’m sure someone can correct me if that’s wrong – and Kathleen Stock was interviewed in the Guardian which was amazing. Those of us who had been trying to get interviews with these women cheered about it but, as far as I know, her book was not reviewed by the Guardian, and nor was Abigail Shrier’s, who wrote about the effect of trans activism on girls. And nor was Helen Joyce’s huge bestseller about gender ideology.

But we did review and extract, it seems to me, every single trans memoir that came out.

So there was always this imbalance. And I know that upper management, you know, say “Well, both sides are equally passionate,” you know, it’s very hard to balance both the gender activists and what people call gender-critical feminists and I call reality-based feminists. But the fact is, only one side in that argument demands censorship. I have no problem and never had any problem with the Guardian interviewing and spotlighting transactivists, and transactivists’ books, but I was not allowed and nor was anyone else allowed to interview gender-critical feminists, or…

Emma Barnett: There are some, I suppose that’s the point.

Hadley Freeman: There is one: Kathleen.

Emma Barnett: And I did read an interview with Maya, but I think in the Observer.

Hadley Freeman: In the Observer.

Emma Barnett: And we should say, just again, if you’re not familiar with the media world, the Observer is edited by a different editor.

Hadley Freeman: Yeah, that’s right. It’s edited by a different editor.

Emma Barnett: Okay. So because part of your resignation letter I mentioned was leaked to Private Eye, which was to Kath Viner, who we have invited on.

We didn’t get Katharine. The invitation is still open. But we did get this statement from the Guardian, which said:

“The Guardian has always been committed to representing a wide range of views on many topics in our coverage. There will always be debate on the issues we cover. The issues around trans people’s rights and gender critical feminism are complex and can be polarising and polarised. As such, the Guardian aims to feature a wide range of reporting and multiple perspectives on this topic. All writers work with their editors to decide the topics on which they write. This is a completely standard practice across the media. That is not censorship. It is editing.”

Hadley Freeman: I understand what they’re saying and, you know, I’m not an idiot. I was there for 22 years; I had a column for most of those 22 years. Of course, you know, you discuss with the editor what you’re writing beforehand, but on no other subject had I ever been told, “You are not allowed to write about this”, wholesale.

Emma Barnett: Who said that?

Hadley Freeman: It was someone quite high up in the paper.

Emma Barnett: So it was actually said to you –

Hadley Freeman: Yes, you are not allowed to write about gender, and also, they said to me at the same time, I don’t want any women to be writing about gender because it gets too much of a kickback on social media. It should be done by the male specialist reporters, such as the health reporters.

Emma Barnett: So that was said to you by an individual.

Hadley Freeman: It was said to me in a meeting with three other people who can all back me up on that.

Emma Barnett: And I’m asking because I also was interested, it’s been said to you by the editor herself?

Hadley Freeman: I don’t want to be naming and pointing direct fingers. It was said by upper management. It was clear that was the policy.

Emma Barnett: Because there are a couple of pieces, which I know we’re also going to come to, because of what then happened with those pieces, where you have written and shared your view. Are you saying there was a policy change, because they’re about four years old?

Hadley Freeman: Yeah. That was a policy change. So I wrote I think two columns in my magazine column, which I had at the time. One was about Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, about the interview she gave, and one was about progressive men using gender activism as a guise to be incredibly misogynistic and to shout at women, mainly online, but also in life. And I wrote those and there was a huge backlash online and also within the office, and then I went to America for work and I was there for a bit, I think covering the Oscars or something and came back –

Emma Barnett: You did have quite a broad range, through from people who are fashion, through to politics.

Hadley Freeman: I like to write about most things really. I’m not myopic in that sense. And I came back and that’s when I was told that I wasn’t to write about gender and actually women shouldn’t write about gender, etc, etc. And suddenly, things became very, very tricky for me and you know, I asked if I could interview Martina Navratilova after she wrote a column in the Sunday Times, about why she didn’t think trans women should compete against female athletes, and I was told that my point of view and Navratilova’s point of view were mean. You know, I would –

Emma Barnett: You were told that your point of view was mean?

Hadley Freeman: Yes, that was the quote, I was told.

Emma Barnett: Sorry.

Hadley Freeman: And, you know, other people, Jess de Wahls and other women who’ve had trouble with gender activists, and it was always no, no, no. And then I was told, a few months after this began, that while I was away, a group called All About Trans, which is I believe the best way to describe them would be a lobby group, who go around to different companies and media groups and talk about how trans people should be discussed or written about, had come to the Guardian, and they’d held up two of my articles as examples of transphobia. And I was told this had happened about eight months previously, while I was away, and when I went to HR and some of the editors and asked, you know, could they send out a message to my section editors, who had been at this event – and also I should say All About Trans, you know, consisted of people from Mermaids, and Mermaids had been at this event too, I was told. So when I said can you let my section editors know and my colleagues know that this isn’t fair, that you know you don’t believe this? And I was told they couldn’t because it would draw more attention to the claim.

Emma Barnett: So you found out months afterwards that while you were away your place of work had had a session by an external group welcomed by, I believe, the Guardian Pride group, which is a group of staffers within the place, and your two articles were held up as transphobic?

Hadley Freeman: Yes.

Emma Barnett: And you weren’t told about that in advance?

Hadley Freeman: Ha! God no, and I wasn’t told about it immediately afterwards, I just found out when a friend and colleague happened to mention it to me, saying she thought I should know as it was clear no one had told me, because I kept saying to her, “I don’t understand what’s changed”. And there did suddenly become this atmosphere of real fear in the paper. And there were various morning conferences, to which all people who work at the Guardian are invited at the beginning of the day – we don’t really have those anymore, but pre-pandemic it would be everybody gathering, talking about the news. And there was one of those conferences where the paper had run an editorial defending the Gender Recognition Act and why it shouldn’t be made easier for people to change gender, and I was defending the editorial which had run in the paper, and various colleagues and people I considered friends were being quite personally abusive and you know, saying that was transphobic, that it was just like people saying a gay teacher shouldn’t teach children, and I got very upset and I’ve never gotten upset in the office before and I just walked out. Meanwhile, the top editors were all at the meeting, no one said anything, no one intervened.

You know, I understand it’s a subject that gets very heated, but in my memory, and as far as I know, and I’ve looked back on all my correspondence because I’ve saved all my emails, I’ve tried to be very calm and measured and look at, you know, both sides of it. Of course I do. And what you get from the other side, if you’re just trying to defend what is literally the law in this country, is being told you’re killing children, you know, you’re a bigot, you’re this, – it’s this very violent way of talking. And it’s not that that upsets me, I can take that, what I don’t understand is why upper management are scared to deal with it. And it seems to me that it’s not just the Guardian.

I don’t want to just be focusing on the Guardian, although obviously, it’s where I worked. This has happened at a lot of progressive places. This feeling of fear that we can’t stand up against some of the claims that gender activists made. You know, it’s happened at the New York Times, it’s happened at the Washington Post, you know, even on Woman’s Hour, I’m not trying to make anything awkward for you, Emma, but I remember a few years ago, when Jenni Murray was still here, and she wrote a piece in the Sunday Times that some people got upset about, she then wasn’t allowed to talk about this issue, as far as I know, on the programme. I remember another time here when there was going to be a debate in the studio, and Stonewall said they wouldn’t come in if the journalist Helen Lewis was here, and in the end Woman’s Hour capitulated to them and allowed them to do a pre-record, which is therefore then not a discussion –

Emma Barnett: Well, you make out – I don’t know about that particular one at all. While I was here I’ve done a lot of interviews, with the CEO of Stonewall, with Kathleen Stock, we’ve done many items on this. Nor can I speak to any of the previous decisions before I joined.

Hadley Freeman: No, no of course, I mean, I’m not –

Emma Barnett: The issue about what you discussed about Jenni Murray, though, I think it is fair to say it’s quite clear that BBC presenters are not meant to have opinions. So we could debate that. But that is your take on it. And I think we could also just talk about processes as well, but again, I wasn’t here for that.

Hadley Freeman: Yes, of course. No, I’m not trying to get at Woman’s Hour, I’m saying that this is something that has happened –

Emma Barnett: [both talking]… we’re a bastion of left-leaning journalism at the BBC like the Guardian…

Hadley Freeman: Absolutely.

Emma Barnett: …wants to be. But your bigger point is that you feel on this that there is on the left side – what?

Hadley Freeman: Well, I think what there is a real feeling of fear because what Stonewall, and other organisations like that, have been very successful at is saying that gender rights are the same as gay rights. And anyone who objects to any element of the gender activism is basically a homophobe. And so there’s this fear on the left, particularly in progressive circles, of getting it wrong, because the worst thing to be would be a bigot. My personal feeling is if you have fear, if you’re scared of saying what is literally in front of you, if you’re scared of voicing doubts, because of what people in the office might say, because of what strangers online might say, then you probably shouldn’t be a journalist. You know, a journalist is about –

Emma Barnett: Do you think the Guardian is scared? And do you think she shouldn’t be in her job?

Hadley Freeman: Oh my, I mean, I’m not going to –

Emma Barnett: Well you’re busy saying, you know, various programmes have capitulated without knowing the background. You do know the background of your newspaper.

Hadley Freeman: [laughs] I do know the background at my newspaper.

Emma Barnett: And you’re not short of opinions. And unlike Jenni Murray, when she was at the BBC, you’re allowed to say them, you’re paid for them. So do you think she should be in her job? It’s a very serious allegation to say the editor of the biggest left-leaning newspaper in this country is censoring women from writing about gender. Should she be in the job?

Hadley Freeman: I didn’t say that the editor had censored, I said –

Emma Barnett: Oh sorry. She presides… Sorry, but management is management. And when you say upper management, she’s presiding – okay, I’ll rephrase. She’s presiding over management, which told you with witnesses on several occasions, and your articles were used within the organisation’s hosting of groups, that you’re not allowed to write about certain things. That’s a very serious allegation.

Hadley Freeman: Yes. And it’s happened at other places, too. I mean, you know, I –

Emma Barnett: Do you think she’s fit to be the editor?

Hadley Freeman: I’m sure she’s fit to be the editor. What I’m saying is it’s not right for any newspaper to censor on any specific subject.

Emma Barnett: Why is she then fit to be the editor?

Hadley Freeman: I’m not going to try to push her out of her job, Emma.

Emma Barnett: No, no, but some of our listeners will read the Guardian. They want to know they’re being shown a full range of views. Some of them may push back I mean, I was just looking at the Mermaids articles from the last few days. Those articles have been written up as straight news articles on the Guardian website.

Hadley Freeman: Yes. After I left.

Emma Barnett: After you left. Ah, you have left already and not started yet [at the Sunday Times].

Hadley Freeman: Yes.

Emma Barnett: But I suppose that some would also say other parts of the paper, maybe the sports section, do you think that has been better?

Hadley Freeman: Yes.

Emma Barnett: At writing about some of the issues and trends there?

Hadley Freeman: It has.

Emma Barnett: Because, okay, fine, because it’s interesting to try and compare if there’s a difference. You and I both know how newspapers work, again, I’m trying to reveal – the news desk, the comment desk, the sports desk: different editors.

Hadley Freeman: Yeah, and this is why I’m not trying to target Kath Viner in particular: I mean, there are different section editors all around the paper. And sport has been good at this. There’s a columnist, Sean Ingle, who has been very good at writing about the science behind this. But I do know as well that there have been lobby groups that have come in to talk to the sports desks, arguing the case for trans athletes, transwomen athletes to be competing as female athletes. As far as I know, there hasn’t been a group like Fair Play For Women defending why women’s sport needs to be female sex only. You know, I understand why I’m sure people at the Guardian will think I’m just here slamming the Guardian and to be honest, that breaks my heart because …

Emma Barnett: Yes, you cared about it!

Hadley Freeman: … the Guardian and was my whole life for my entire adult life. But the Guardian is representative of so many other progressive spheres, academia, publishing exactly the same.

Emma Barnett: Do you think something is changing?

Hadley Freeman: Well, I think this coming year is going to be very interesting, because obviously GIDS, the clinic run by the Tavistock Trust, is shutting down and it’s no longer about children being funnelled there – gender non-conforming, whatever that even means. Children will not be funnelled there, there will be various regional hubs, and Mermaids is under investigation. I think more and more people are looking at what this gender ideology actually means in practice rather than theory, rather than the “be kind” theory. What does this actually mean for children and for women, and for you know, gay people? I really do see this idea that gender non-conforming is problematic, which is what gender ideology is based on, as a backlash against both feminism and gay rights. And I think there are increasing numbers of gay people who are speaking up against it too.

Emma Barnett: We will talk again, I’m sure, about these issues of which there are many and there are different views as you well know, and you said, you want the other views there; you just want your views as well, and the ability to have it. I didn’t mention this and I just want to make sure I go back to it. The other concern in your resignation letter was about your ability or being allowed to write about antisemitism in the Labour Party, with a Jewish background, a Jewish identity. Again, I presume within this statement we’ve got from the Guardian that is also refuted, but what do you say about that?

Hadley Freeman: What happened there was I was given the column at the front of the magazine in I believe, 2015. And no one said, you can’t write about any subject. In fact, when I started at the Guardian and the magazine was edited by Kath Viner, who is now the editor of the paper, that column was done by Julie Burchill and certainly no one would ever dare tell Julie Burchill she’s not allowed to write about a certain subject. And then Corbyn got in and I wanted to look at his, you know, this feeling that he had a blind spot, as they say, when it comes to antisemitism. And I was told that that column was not for politics. It wasn’t a political space. It should be softer, more cheery-uppy, which no one had told me when I started, and I thought, okay, you know, I’m a grown up, fine. I’ll do my job. Okay, carry on.

Then the gender ideology started to take off a lot and I thought, well, this seems a more generalised subject, you know, writing about women. You know, what does being a woman mean? And then I was told no, I couldn’t write about that either. That was too punchy, was too something. And then we saw what happened, I’m sure some of your viewers or listeners know what happened when Suzanne Moore wrote a column in the feature section about her experience of being a woman through her biology, it then resulted in 330 staff members signing a letter objecting to the pattern of transphobic content in the paper, none of which was specified. So it’s not –

Emma Barnett: It stemmed, you would say, from your experience of being told no about Jeremy Corbyn’s side of things through into this.

Hadley Freeman: Yeah, I feel like there was a through line.

Emma Barnett: Yeah, I mean, of course, Sir Keir Starmer has talked a lot about, for instance, accepting the findings of the EHRC report which looked into the Labour Party on this, saying it had committed unlawful acts, saying “We’ve closed the door on a shameful chapter in our history about antisemitism”, for those who also want to respond to that. Just finally, because you mentioned the fantastic Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, I’ve had her on the programme, I’ve spoken to her a number of times, about her and her response around this particular topic, around gender. She’s just given one of the Reith Lectures here at the BBC and she’s talked about self-censorship, she worries that this society – just broadening this right out which I know interests you – is suffering from an epidemic of self-censorship, young people growing up afraid to ask questions for fear of asking the wrong questions, and she’s worried about the death of curiosity. What would you say to that?

Hadley Freeman: Well, I know that’s true. When I stood up for Suzanne Moore in the morning conference after this column came out, I had various staff members, not necessarily young people, people my age and older, coming up to me, whispering, or sending me emails saying “You know I back you, I just can’t speak up”. “It’s just too difficult in the office” or “it’s too difficult with my teenagers at home”. Of course we know this, you know, it’s very hard to go against what you’re told is the mantra for your political tribe. And that is what I think is happening. And the fact is, as much as the Guardian or New York Times or whoever would want to make this argument as gender-critical women on the right, gender activists on the left, we know it’s not that simple. It’s not, that’s a lie. You know, women are just trying to protect their existing rights.

Emma Barnett: Hadley, thank you very much. I hope you feel you were not censored in any way in that conversation. You got it out and gave us a window into perhaps what people don’t really know about newspapers as well as anything else. Good luck with the new post at the Sunday Times and the book, perhaps we’ll also talk about that. And I read aloud the Guardian statement. And I mentioned we’ve invited the editor of the Guardian, different to the editor of the Observer, on to the programme, Katharine Viner, so I do hope she’ll take us up on that, we shall see. While we’ve been talking, you have been sending some messages about what Hadley’s got to say and I hope to come to those.”

While we’ve been talking, you have been sending some messages, about what Hadley’s got to say and I hope to come to those. You’ve also been sending in songs. The ones that have got you through this year – have you got one, Hadley?

Hadley Freeman Yes, so my most listened-to song was ‘All Too Well’, the 10-minute version.

Hadley Freeman’s first column in the Sunday Times