A policy in search of evidence

Why we need to treat with caution claims about the specific harms of keeping trans-identifying men in male prisons

The Macdonald-Laurier Institute in Canada has published a monograph, Rights and wrongs: How gender self-identification policy places women at risk in prison, by Professor Jo Phoenix.

In the foreword Patricia Craven, a former prison governor at HM Prison Service, England and Wales, says:

“I hope that this balanced and measured report, which provides a striking insight into an issue that is largely locked away from public view and yet affects the most vulnerable women in the country, will finally prompt decision-makers to ask themselves some long overdue questions, to gather the necessary data and to stop the baleful impact of this policy on women.”

Professor Phoenix has written a guest blog post for Sex Matters which assesses the evidence on the vulnerability of trans-identifying males in men’s prisons.

The reasons for placing male prisoners who identify as women in the female prison estate can be broken into political (“transwomen are women”), legal (it is discriminatory not to) and social-scientific. The social-scientific evidence would have us assume that trans-identifying males are at risk of sexual violence, suicide and poor mental health if they are housed in male prisons. But how robust is the evidence?

Sexual violence and victimisation

There is a robust evidence base that shows that transgender prisoners are at significantly greater risk of sexual violence in male prisons – but it comes entirely from the USA. Jenness (2021) found that male prisoners who identify as transgender were sexually assaulted nearly 13 times more than other male prisoners in California’s male prisons. These are appalling statistics.

There is evidence that confirms that transgender prisoners are harassed and bullied by other prisoners and staff, and that officers and prison management fail to recognise or deal with that harassment. Studies also show that the health, medical and social needs of transgender prisoners are often mismanaged. So, for instance, prisoners on cross-sex hormones prior to incarceration were denied them. Other studies demonstrated that males who identify as women can be placed into something called ‘administrative solitary confinement’ where the prison officers decide that the only way to keep a specific prisoner safe is to segregate them from the prison population. Some of the stories in the research are (and should be) profoundly disturbing. They speak to a pattern of transgender males in American prisons facing a double punishment: one for the crimes they committed and the other the result of being a transgender prisoner in a hyper-masculine, toxic environment.

The question that ought to be raised is: what, if any, of this evidence and the findings are applicable to the UK and what are not? British campaigning and lobbying groups use the evidence from the USA as though it is generalisable. I would argue it is not, for the following reasons.

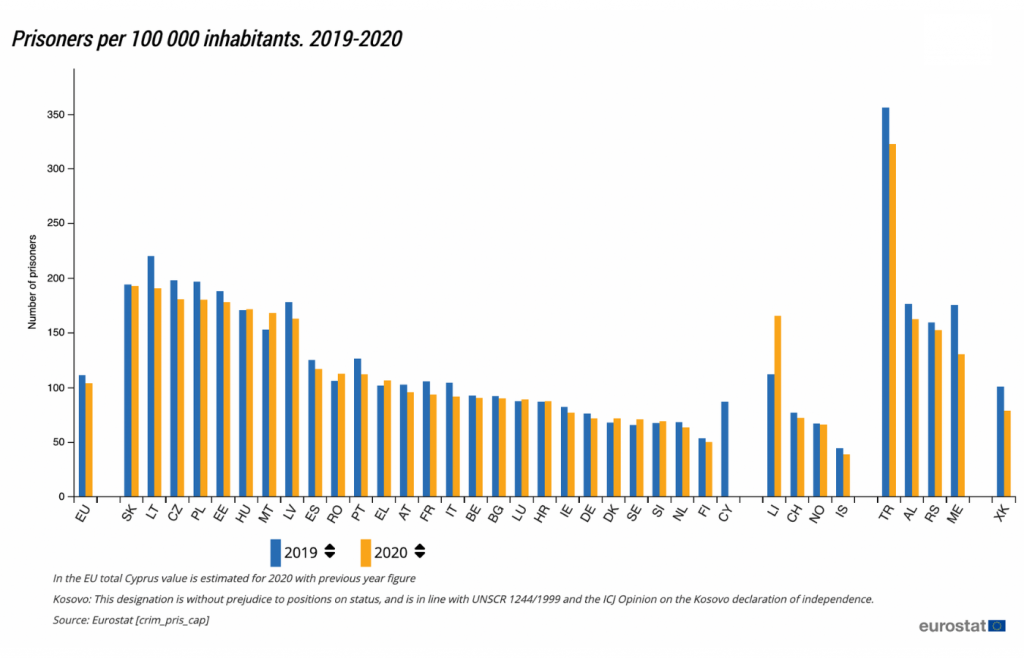

Prisons and penal culture in the USA are not like those elsewhere in the developed world. In criminological circles this is referred to as “American exceptionalism” and entire books, papers and special issues of academic journals have been written to try to explain why America’s penal system is so out of step with the norms of modern democracies. The USA incarcerates at a significantly higher rate than all other modern democracies: European countries incarcerate at a rate of between 100 and 200 per 100,000 (with Turkey an outlier, as below), whereas the rate of incarceration in the USA hovers around 600 per 100,000 of population.

American prisons, some of which still operate the death penalty, are not managed or inspected in the same way as British and European prisons. Conditions can be so appalling that it is reasonable to talk about the mass warehousing of human beings as a state response to crime. Depending where in the USA you are incarcerated, it is impossible not to see the history of racialised social conflict, slavery and explicit policies of racial segregation. American sentencing cultures are also fundamentally different: it is not uncommon to see sentences that are decades long for the sort of crimes that would attract only months in the UK and Europe.

But it is not just penal cultures that are different. The social and cultural politics of sexuality and gender identity are also different. We often assume that the USA is a progressive country, but if the last few years have demonstrated anything, it is that America is a divided country. The ideals of equality and progress do not match the realities of formal legal discrimination and social conflict. Homosexuality was made legal across the USA only in 2006 and even now many states that had adopted progressive laws and practices regarding homosexuality and gender identity are in the process of unadopting them. This is all by way of saying that, at least where prisons are concerned, the USA is so different that there is no reason to assume that evidence from the USA is generalisable, or that basing prison policy in the UK on that evidence is warranted.

Suicide and mental health

Closer to home, we have evidence about prison suicides and mental health, but it too has problems. Inquest (an organisation that collects and publishes data on prison suicides) reported that between 2013 and 2020 there were six deaths by suicide of transgender male prisoners in English and Welsh men’s prisons. During the same period, 782 men and 31 women who were not transgender committed suicide in prisons. Six deaths is equivalent to approximately two percent of the known transgender prison population; the equivalent proportion for non-transgender men and women is just one percent. A cautionary note: the number of transgender suicides and the population of transgender prisoners are so small that it is not possible to draw the conclusion that transgender prisoners commit suicide at twice the rate of non-transgender prisoners. Further, we do not know what puts transgender prisoners at risk of suicide. How do these suicides relate to their gender identity? Or are they related to the same risks that men and women face within the greater system? Official reports into the suicides of three transgender prisoners concluded that the suicides were probably not related to either their transgender status or mismanagement of that status by the prison.

And what of the evidence of mental-health problems? The single report that the Ministry of Justice for England and Wales used to argue for the higher risks of suicide faced by transgender prisoners contained other evidence that could explain higher rates of suicide, although some of it related to the USA and needs to be treated with caution. It showed that, relative to the general population and relative to lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations, transgender prisoners suffer from disproportionately high rates of poor physical and mental health. But there could be a chicken-and-egg problem here. Transgender prisoners’ prior poor physical and mental health may well have an impact on their health once they are incarcerated. So it is difficult to know if being placed in a male prison makes trans-identifying male prisoners unwell or whether their generally poorer state of physical and mental health is exacerbated once in prison.

Whatever the case, the most striking observation I took from my review of the evidence of harm is that a lot is (politically) made of a relatively thin evidence base. Claims that trans-identifying males are at risk of poor mental health, sexual violence and suicide if placed in male prisons are based on little to no evidence. When it comes to the risks they pose to other inmates, there is no systematic evidence – with the important exception that there are quantifiable risks that some trans-identifying men, who are also sexual offenders, pose to female prisoners. In practice risk assessment, therefore, means little more than asking a professional to use their judgement and discretion. The risk that is being assessed and managed is a consequence of government policies that prioritise the safety, dignity and mental wellbeing of trans-identifying male prisoners over the safety, dignity and mental wellbeing of female prisoners.