Searching for a simple answer

What does a gender-recognition certificate actually do? The question comes into sharp focus when people are forced to undress, or have to submit to intimate touching. It is a question of central importance to HM Prison and Probation Service’s policy on searching.

Human rights

As the Divisional Court in R (LD, RH and BK) v Secretary of State for Justice [2014] explains:

“The power conferred by Rule 41 [which governs searching in prisons] is of course necessary because, without it, any search, and particularly a strip-search, would constitute an assault.”

The court notes that the European Court of Human Rights (Valašinas v Lithuania, 2001) found that a strip-search carried out in the presence of a person of the opposite sex is degrading and constitutes a breach of Article 3 (which concerns torture and degrading treatment). Even the more frequent “rub-down” search (over clothing) can engage Article 3 and 8.

In the Corston report (2007), Baroness Corston described the effect of strip-searches on women in particular as “humiliating, degrading and undignified, a dreadful invasion of privacy”.

Access all areas?

Apart from “rub-down” searches (where female staff are allowed to search men) searches of prisoners, staff and visitors must be undertaken by a staff member of the same sex as the person being searched.

The policy has to deal with what happens if a prisoner, staff member or visitor identifies as transgender. The previous policy (psi-07-2016) considered a combination of anatomy and legal status of prisoners.

On 3 October 2022 the Prison and Probation Service issued a new Searching Policy Framework, which focuses solely on their legal status (i.e. whether someone has a GRC or not).

“Prisoners should be full searched applicable to the acquired gender, irrespective of their bodily characteristics (including genitalia). In practice, this means that male to female transgender prisoners in receipt of a GRC should be full searched by female officers and female to male transgender prisoners with a GRC should be full-searched by male officers. To do otherwise would incur a significant risk of litigation.”

What about transgender staff?

It is central to the policy that staff should be the same sex as the person being searched (except where women are patting down men). But the new policy swerves a critical question – what happens if a staff member has a GRC?

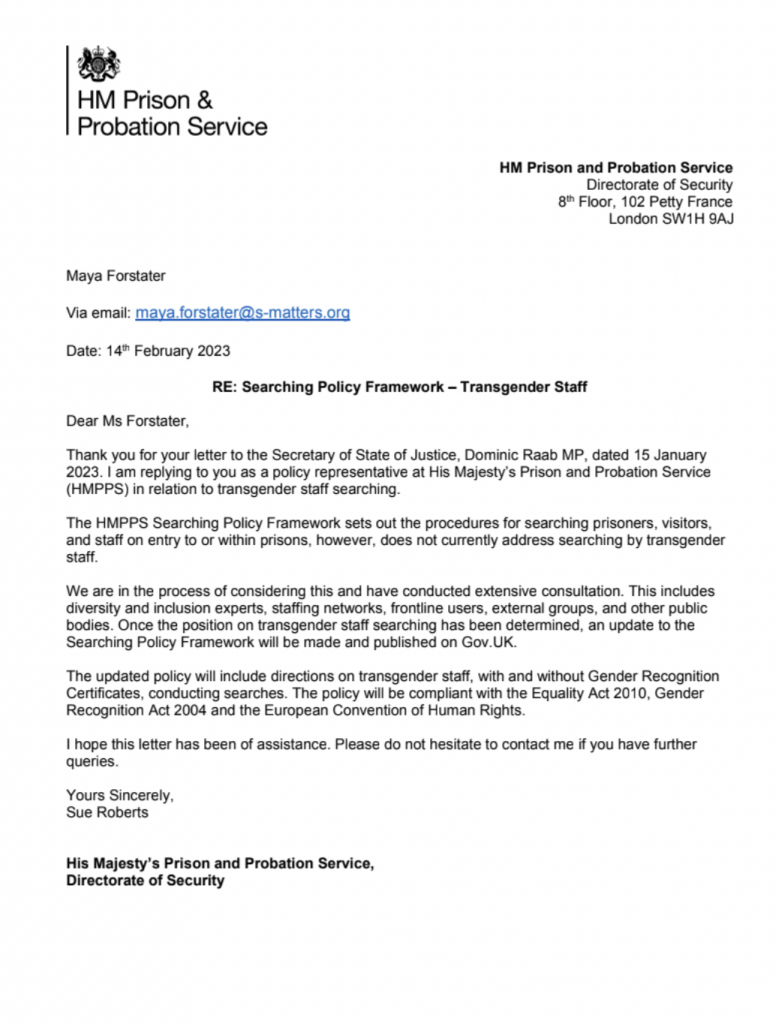

We were consulted on this over 18 months ago, so we know that the Prison Service has been thinking hard about it. When we wrote to the Justice Minister asking what the new policy means by “same sex”, Sue Roberts of the Prison and Probation Service wrote back saying that HMPPS was still considering the question.

She said that the new Searching Policy Framework would be updated again with directions on transgender staff, “with and without Gender Recognition Certificates”, but gave no timeframe for when this would be done.

Letter from HMPPS

A simple answer

We think the answer is really simple. No.

- Should a woman or girl be forced to be searched by a man? No.

- Should a woman officer be obliged to search a man? No.

- Does it matter if the man identifies as a woman? No.

- Does it matter if the man dresses as a woman, or prefers feminine pronouns? No.

- Does it matter if that man has a piece of paper saying he is a woman? No.

A strip search of a woman or a girl by a man would constitute humiliating treatment and a clear infringement of Article 3. Even in the case of a rub-down search, it could breach Article 3 and Article 8. A GRC does not change that.

Nor should an employer compel staff to commit assaults.

Equally a person may reasonably object to being searched by someone who has adopted the appearance of the opposite sex (particularly via extreme body modifications) and who refers to themself as a member of the opposite sex.

Lawful exceptions

Is it unlawful discrimination to restrict trans prison officers from searching prisoners?

No.

The Equality Act contains exceptions to the general prohibitions on sex discrimination and gender-reassignment discrimination, that would cover the case of trans prison officers (whether or not they have a GRC).

And there is a more fundamental reason why excluding trans staff from searching duties would not be discrimination, even without the exceptions. Not being allowed to commit sexual assault is not a detriment. Any affront felt by a trans person who is not permitted to search someone is an unjustified sense of grievance, which cannot amount to “detriment”: Barclays Bank plc v Kapur (No 2) [1995] IRLR 87.

Why is HMPPS taking so long to come up with an answer?

We think the only answer that is compatible with other people’s human rights is:

Searches that are supposed to be carried out by someone of the same sex as the person being searched must be carried out by someone of the same sex as the person being searched.

Why is this not obvious to officials at HMPPS?

One reason is that they have previously received legal advice that a GRC confers the legal right to be treated as the opposite sex in all respects. As the then Justice Minister, Lord Wolfson of Tredegar, told the House of Lords in 2021:

“Prisoners and staff members in receipt of a GRC have the right to be treated as their acquired gender in every respect.”

As the policy notes they think they would “incur a significant risk of litigation” in the case that they refused a male prisoner with a GRC having the service of a female prison officer searching them.

We think this advice they have been given is wrong. And it ignores the risk of litigation on the other side, from prisoners, visitors and staff forced to be searched by members of the opposite sex, and from female staff pressured to strip-search males with a GRC.

While it is frustrating that it is taking this long to reach a simple answer, we are encouraged to hear that the updated policy “will be compliant with the Equality Act 2010, Gender Recognition Act 2004 and the European Convention on Human Rights”.

Perhaps it is taking so long because HMPPS is being lobbied by external groups such as Stonewall, and by internal groups such its Pride in Prison and Probation staff network. This network calls recognising sex differences “transphobic” and has sent an internal email saying that “protect women and girls” is a “coded term which means that a person believes trans women do not belong in women’s spaces”. Civil-service networks such as a:gender are also influential. Steph Calvert (pictured above), a frontline Border Force Officer who has led this network and identifies as female, compares single-sex spaces to apartheid and racial segregation.

These special-interest groups have been arguing since before the Gender Recognition Act became law in 2004 that people who declare a trans identity should be allowed to conduct searches and intimate examinations of members of the opposite sex. In 1999, when the protected characteristic of gender reassignment was first added to the Sex Discrimination Act, trans lobby group Press for Change vigorously opposed the exception for intimate searches.

In the tussle over whether men who identify as women have the right to touch and look at women’s bodies without those women’s consent, anyone who objected has been smeared as a “transphobe” and a “bigot”, and threatened with losing their job.

Breaking the spell

We think there could be a deeper reason why this particular policy has become so stuck.

Trans rights are human rights. And human rights are universal.

Once it is recognised that a GRC does not give a male prison officer the right to search female visitors, prisoners and colleagues, it will be clear that the same principle applies in other places where searching takes place.

- A male teacher with a GRC saying female does not have the right to search a female student.

- A male police officer with a GRC saying female does not have the right to search a female suspect.

- A male airport-security officer with a GRC saying female does not have the right to search female passengers or female colleagues.

And once we say that a GRC does not give men the right to run their hands over women’s and girls’ bodies, or to watch them strip in the context of searching, what about the privacy and freedom from humiliation of women such as the female staff members at the Sheffield Hospital who were told they had to share showers and changing rooms with their trans-identifying male colleague? What about the college students told to strip naked in front of Adam Graham? What about the women forced to share locked mental-health wards with men who identify as women? What about the women at Jaguar Land Rover forced to share toilets with a male colleague who identified as “non-binary”?

What about the policy of housing trans-identifying males in prison with women at all? In the case of FDJ v Secretary of State for Justice [2021] EWHC 1746 (Admin), a female prisoner tried to assert her right not to be locked up with male sex offenders. But the court dismissed this, saying:

“It is not possible to argue that the Defendant [Ministry of Justice] should have excluded from women’s prisons all transgender women. To do so would be to ignore, impermissibly, the rights of transgender women to live in their chosen gender.”

Once we have noticed for one purpose that the right to “live in a chosen gender” (with or without a certificate) is not a right to distort reality, subject other people to humiliating treatment or compel others to act as if they believe the person has actually changed sex, we have noticed it for all purposes.

Transgender people have the same human rights whether or not they have a GRC. The prison service already recognises that a trans person without a GRC does not have a human right to search or be searched by members of the opposite sex, how could possession of a government-issued certificate change that?

No wonder civil servants at HMPPS are pushing this hot potato around their desks, leaving staff on the ground to do their best to navigate the issue in practice without any policy.

Nobody wants to be the person who writes the policy that says a teenage girl visiting her father in prison can be forced to submit to a male officer with a government certificate running his hands under her breasts, and his fingers around the inside of her waistband and across the back of her skirt.

But nor does anyone want to be the person who notices that this girl has rights. Because if this girl has rights, so too do all the other girls and women whose interests have been so casually discarded in the name of “trans inclusion”.

Trans rights are human rights – and other people’s rights are human rights too.