Male and female in the Equality Act

Last week Old Square Chambers hosted a seminar about single-sex services and the law. Barristers Nicola Newbegin and Robin Moira White argued that biological sex is something that “popped up” recently in relation to the Equality Act.

The meaning of the protected characteristic of “sex”, they said, is ambiguous and does not correspond to biological sex (and therefore the single-sex service exceptions are complex and difficult to use).

We disagree.

How does the Equality Act 2010 define sex?

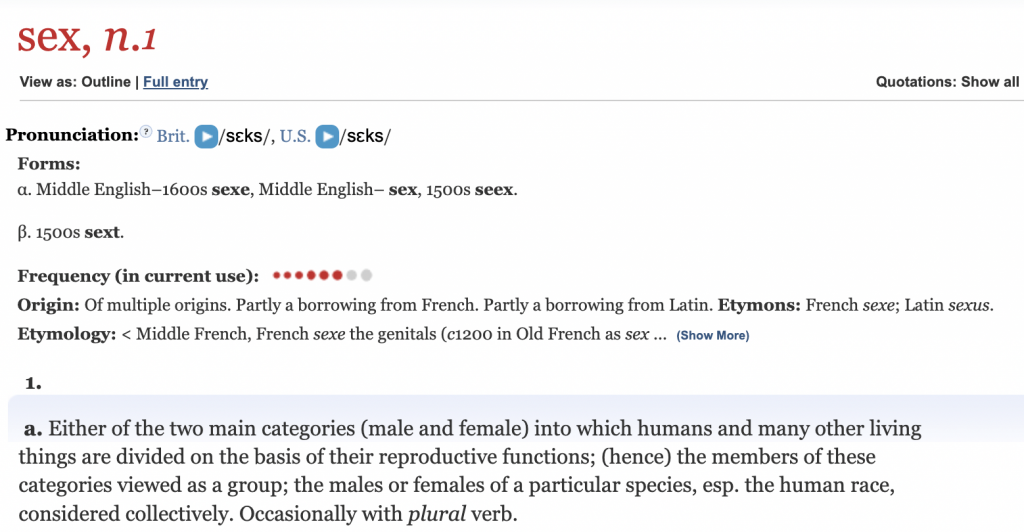

Nicola Newbegin began by acknowledging that section 11 of the Equality Act 2010 provides that sex is “a reference to a man or a woman” and that section 212 gives the definitions “a man is a male of any age” and “a woman is a female of any age”.

But, “The Act provides no further guidance”, she said, and “importantly, there is no definition of biological sex”.

Is a definition of these plain English words really needed? The ordinary meanings of “male” and “female” seem straightforward enough to anyone who has kept pets, or had a sexual relationship.

Newbegin said that Section 7 (Gender reassignment) “talks about the physiological or other attributes of sex” and that this suggests that “the Equality Act recognises sex as being more than purely biological”.

Robin White criticised the EHRC for publishing new non-statutory guidance on single-sex and separate-sex services which clarifies upfront that “sex” is understood as a binary, meaning biological sex, saying:

“Understood by whom, and where?… This concept of biological sex appears, apparently from nowhere. It isn’t in the Act. It hasn’t appeared in the guidance, it doesn’t appear in the statutory code, it just seems to have popped up from nowhere.”

Did biological sex really only pop up recently?

Certainly this was the view of a working party of the Employment Lawyers Association, made up of White and Newbegin, together with Paul McFarlane, Harini Iyengar and Shah Qureshi. They found the law confusing and concluded in their submission to the Women and Equalities Committee in November 2020 that the meaning of “sex” was uncertain.

But the meaning of “sex” is not unclear in law. As the judgment in Forstater in June 2021 confirmed:

“The Claimant’s belief that sex is immutable and binary is, as the Tribunal itself correctly concluded, consistent with the law … The leading case is still Corbett v Corbett [1970] 2 All ER (at 47, 48 and 49) per Ormrod J. Its effect was considered by the House of Lords in Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police v A (No.2) [2005] 1 AC 51…”

That Employment Appeal Tribunal accepted the arguments of Ben Cooper QC and Anya Palmer about sex and gender in the law, and rejected those of Jane Russell, counsel for the respondents:

“Ms Russell sought to persuade us that the decision in Corbett is outdated and should not be followed, particularly in light of the GRA under which a person who obtains a GRC does ‘become for all purposes’ the acquired gender. We cannot see any real basis on which this appeal tribunal could disregard Corbett especially given that the House of Lords’ comments in Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police v A (No 2) were made having regard to the Gender Recognition Bill…”

The section on “sex, gender and the law” from Cooper and Palmer’s EAT skeleton argument is worth reading if you want a run-down of the case law. They argued that sex is a biological characteristic fixed at birth based on chromosomal and physical characteristics, whereas transsexual gender identity is a different category of thing (based on the cases of Corbett v Corbett [1970], Bellinger v Bellinger [2003] and Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police v A (No 2) [2005]).

As Lord Hope noted in Bellinger, gender reassignment treatment and surgery may give someone some of the physical characteristics of the opposite sex, but medical science “is unable, in its present state to complete the process. It cannot turn a man into a woman or turn a woman into a man”.

A person’s biological sex remains a material reality.

Sex in the Equality Act: not so mysterious

The Equality Act 2010 (and the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 before it) uses the word “sex” in the same way as the dictionary. It is a basic category of biology and is reflected in common law.

The Equality Act protects against sex discrimination, which in practice means detrimental treatment relating to the sex that other people know or perceive a person to be, not the sex that a person wishes they were.

Lord True pointed out in a ministerial statement a few weeks ago that in any individual piece of legislation, the meaning of “sex” is not a mystery, but could mean only one of two things, depending on policy intent:

1) biological sex, or

2) sex as modified by a Gender Recognition Certificate

Where a law refers to pregnancy and birth, it is clear that the policy intent is to refer to biological sex.

The Equality Act 2010 is full of references linking the concept of “woman” and “sex” with pregnancy and childbirth, which remain among the main reasons women face discrimination at work.

S.13 (6) of the Equality Act 2010, for example, provides:

If the protected characteristic is sex –

less favourable treatment of a woman includes less favourable treatment of her because she is breast-feeding;

in a case where B is a man, no account is to be taken of special treatment afforded to a woman in connection with pregnancy or childbirth.

It seems quite clear that when the Equality Act says a woman might be discriminated against because she is breastfeeding, or that maternity provisions do not discriminate against a man, that it recognises the words “woman” and “man” as relating to option 1: the two biological sexes.

Lord True’s statement suggests that a way forward might be to amend legislation to make this absolutely clear. No one should have to worry, or argue, or draw on complex case law when they are undressing in a space which they have been told is single-sex. And no one should lose their job for stating clearly what the law recognises about the two sexes.