EHRC issues guidance on discriminatory adverts

As the EHRC says, an advert is a notice or announcement – written or oral – promoting a job opportunity, product, service or event. Adverts might appear in newspapers or magazines, on the television or radio, in shop windows or emails or on a website. They can also appear on doors and buildings.

Adverts tell you whether a job, product or service is suitable for particular types of people. Under the Equality Act it is usually unlawful to restrict services to people with a particular protected characteristic (such as an age, sex, race or belief). But it is sometimes lawful, such as where the service requires bodily privacy , or is only safe for people of a particular age, or if the job requires someone of a particular religion.

Here are some examples of adverts that restrict goods, services or jobs to people with a particular protected characteristic. See if you can work out which are lawful and which are unlawful:

A. “No Ladies” signs in pubs, 1970s

B. Poster for “mother’s only fitness”

C. “No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs” sign (apocryphal)

D. “Ladies” sign on toilets, showers or changing rooms

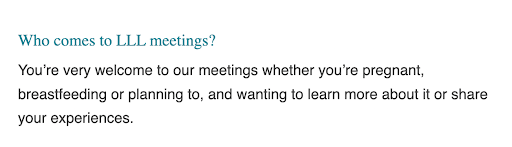

E. La Leche League charity description of its service for breastfeeding mothers

F. “Waitress wanted” sign

G. “Women only” sign at Kenwood Ladies’ Pond, London

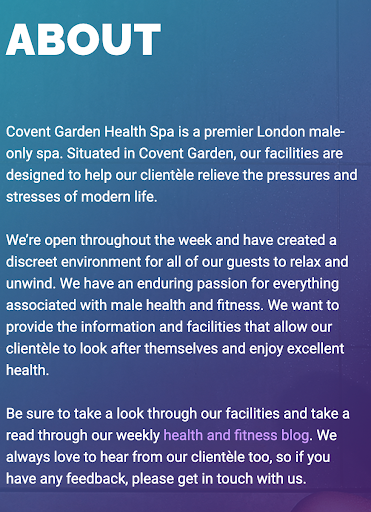

H. Covent Garden Health Spa website (men only)

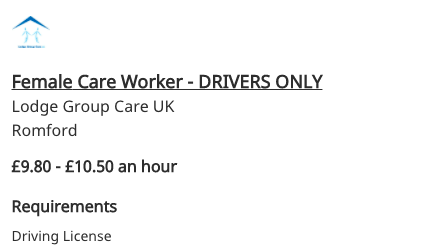

I. Advert for a female care worker

J. Playground sign with age restrictions, Camden

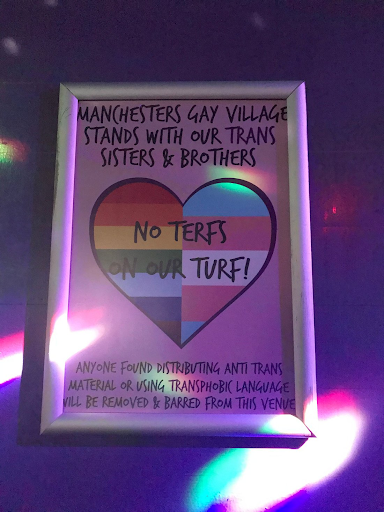

K. “No TERFs on our turf” sign, pub, Canal Street, Manchester

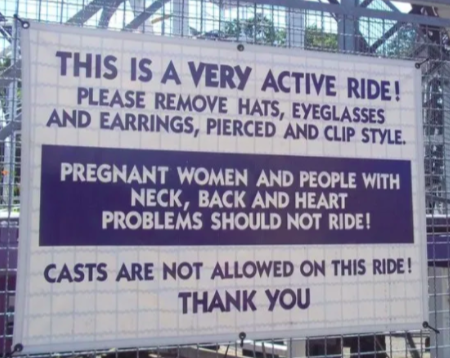

L. “No pregnant women” sign on a fairground ride

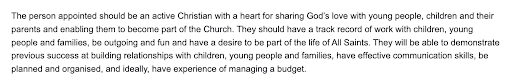

M. Advert for a Christian youth worker

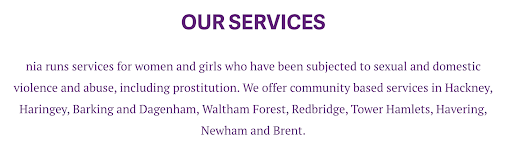

N. Description of a women’s domestic violence service

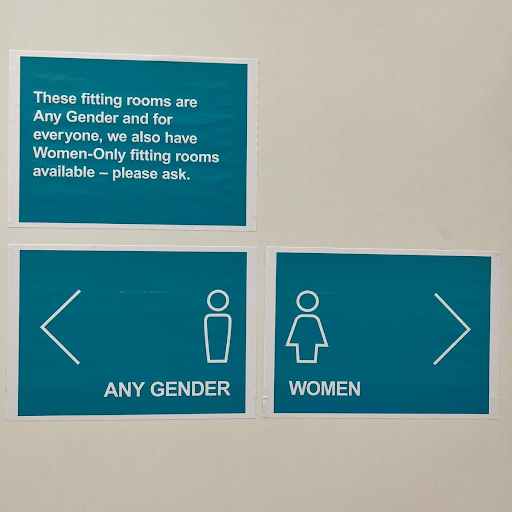

O. Women’s changing room sign, Primark

Most of these adverts are examples of lawful discrimination allowed by the Equality Act. Four are unlawful: A is unlawful sex discrimination, C is unlawful race discrimination, F is unlawful sex discrimination and K is unlawful belief discrimination.

As the EHRC says, the Equality Act allows services to be restricted, often requiring the restriction to be objectively justified as a “proportionate way of achieving a legitimate aim”. This justification applies at the general level to the rule or requirement: it does not need to be argued separately for each individual the restriction applies to.

For example, the men’s health spa is a service provided for men. It does not need to provide a separate objective justification for excluding any individual woman.

Everyday signs are lawful

The EHRC says that there are “very limited circumstances under the Act when employers or service providers can target particular groups in their adverts”.

In fact, as these signs show, while these situations are limited in the sense that they are carefully defined, they are not uncommon.

The new EHRC guidance says “an advert should clearly explain the basis and reasons for the restriction”, but as the examples above show, this is rarely necessary in practice, particularly when it comes to services.

Just because an advert or sign is not conveyed in legalistic language, with small print about a schedule in the Equality Act, it does not mean that it is not lawfully using one of the exceptions. A lawful restriction might be conveyed with no words at all.

This is an advert that conveys that the service is provided for men only.

Do you have to use legal language?

Schedule 9 of the Equality Act provides an exception which allows employers to restrict employment to people with a protected characteristic without committing unlawful discrimination, where the application of the requirement is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. This is termed a lawful “occupational requirement”. There are of course other occupational requirements or restrictions, such as having a particular qualification, which are lawful and don’t involve a protected characteristic at all.

Often employers will mention Schedule 9 in the advertisement (such as where a job is for women only) – but they are not required to.

The EHRC’s new guidance says:

“Occupational requirements under Schedule 9 must relate to having a particular protected characteristic as defined in the Equality Act 2010. The protected characteristic of ‘sex’ means a person’s legal sex as recorded on their birth certificate or their Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC). This means that a sex-based occupational requirement that an applicant is a woman – as is common within specialist support services for women, such as rape counselling – will include women who are recorded female at birth and also transgender women who have obtained a GRC.

However, Schedule 9 also permits an occupational requirement to exclude transgender persons where it is objectively justified, and this can include those who have obtained a GRC. A ‘sex-based’ occupational requirement to be a woman under Schedule 9 cannot include transgender women who have not obtained a GRC, as they do not have legal status as women under the Equality Act 2010.”

This means that an employer has a statutory defence against either a sex-discrimination claim or a gender-reassignment discrimination claim (discrimination on the basis of being “transsexual” in the language of the Equality Act) if they seek to employ an actual woman for a job.

We think the EHRC’s explanation of this unhelpfully conflates how an employer thinks about and conveys a requirement in practice and the language a lawyer might use to defend it if this was challenged in court (particularly given the EHRC’s view that sex in the Equality Act does not mean what most people think it does).

For example, a breastfeeding charity advertises to employ women as breastfeeding counsellors who have themselves breastfed their child and have undertaken a course of training to become accredited breastfeeding counsellors. According to EHRC guidance it should state in the advert that the positions are open to women but excluding some women who are transgender persons (males who have a gender-recognition certificate saying that they are women), but that the position may be open to other women who are transgender persons (females who identify as transgender and do not have a gender-recognition certificate) and to men who are transgender persons (females who have a gender recognition certificate saying they are men).

This is clearly preposterous (but is the kind of thing that organisations are now having to waste time arguing about).

We think the law is actually much simpler than this. The reason for a restriction of a post as a breastfeeding counsellor or for a rape-crisis centre to women only is based on the objective justification that it is a role that requires a woman to do it. This excludes all men (including those who might have changed the sex recorded on their birth certificate or other documentation).

A previous version of the guidance gave a helpful example of a company providing bicycle courier services advertising for couriers who “must be able to ride a bicycle” – while this might exclude some disabled people, the requirement is necessary for the role and applying it is a proportionate way of ensuring applicants can do the job.

Someone like Mridhul Wadhwa (a man who identifies as a woman) is not suitable for a job requiring a woman, whether or not he has a gender-recognition certificate.

Given the pressures that are now being placed on employers and service providers, we think that the EHRC must be absolutely clear in explaining that organisations can continue to put up signs and adverts that ordinary people can understand, where there is objective justification for a rule, without having to resort to complex legal small print or confusion about everyday language.

If a man who identifies as a woman (and who or may not have a gender-recognition certificate) sees a sign or other advertisement for a job or service that says it is for women only – perhaps it is a job vacancy for a counsellor in a rape-crisis centre, a breastfeeding support worker or a menopause counsellor – he should understand that he is not a suitable candidate.

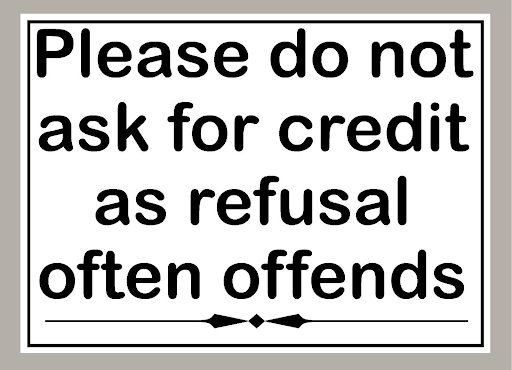

As the old sign displayed in shops said:

Similarly, if a man who identifies as a woman (and who may or may not have a gender-recognition certificate) thinks it would be appropriate for him to seek access to a women’s rape-crisis centre, a breastfeeding support group, a menopause support group, women-only massage lessons, a women-only beauty spa and intimate waxing service, women’s showers at the gym, a female-only sauna, changing room or toilet, or any other service lawfully provided for women only, he would be in the wrong.

The reason is because he is a man.

If he doesn’t think the rule is lawful he can sue, but the service provider or employer has a statutory defence, whether he brings a sex-discrimination claim or a gender-reassignment discrimination claim.

The EHRC guidance suggests that signs or symbols in ordinary language, or simple verbal instructions such as “These changing rooms are for women only” are not clear communication of a lawfully restricted single-sex service. It suggests that there is a separate class of advertisements and signs that invoke esoteric and contested legal concepts that have to be used before you can simply say “No men allowed” in a service, space or role.