Whose schools guidance is in line with the Equality Act?

Joint post with Transgender Trend (it’s long; make yourself a cup of tea). You can also download it as a pdf.

Boys and Girls and the Equality Act

In May 2021 Sex Matters and Transgender Trend published the first edition of our Schools Guidance: Boys and Girls and the Equality Act.

As the introduction states, it draws on the Equality Act 2010, and the safeguarding framework Keeping Children Safe in Education and Working Together to Safeguard Children, as well as guidance for schools that has already been produced by the Department for Education (The Equality Act 2010 and Schools and Gender separation in mixed schools) and the Equality and Human Rights Commission (Technical Guidance and What equality law means for you as an education provider)

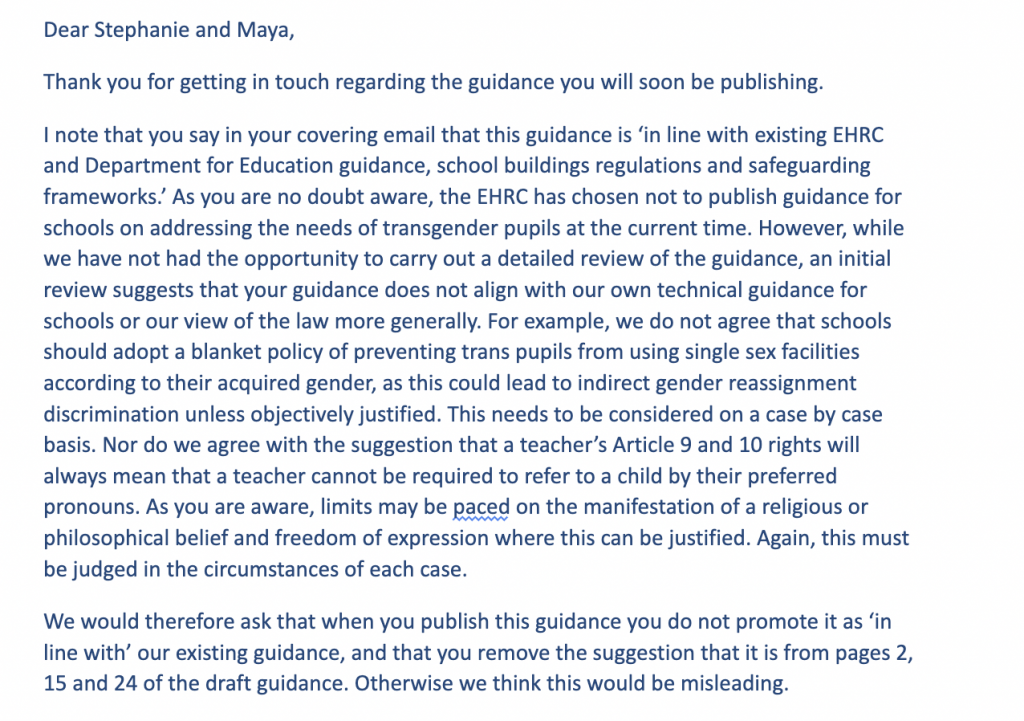

The EHRC’s email

We sent a draft for comment to the EHRC, in which we stated that our guidance was “in line with existing EHRC Guidance and Department for Education Guidance”. The EHRC asked us to remove that language, which we did.

In its reply, the EHRC said that our guide is not in line with its “view of the law in general”.

It is hard to know what the EHRC’s view of the law is.

Schools are having to deal with a rapid rise in children identifying as trans, and are caught between activist demands for unquestioning affirmation on the one hand, and the concerns of many parents on the other. They have been crying out for specific guidance from the EHRC on this subject.

The EHRC started work on such guidance in 2017, with fanfare and talk of suicide risk. The project was launched with statements from Susie Green of Mermaids and Jay Stewart of Gendered Intelligence.

But more than four years later the EHRC still hasn’t been able to formulate and publish its guidance. On 13 May 2021 it admitted defeat, saying that publishing what it had drafted so far “would not be in the best interests of young people” and “may not provide schools with the clarity we hoped”.

We believe our guidance is in line with the Equality Act 2010.

Schools need rules

Our guidance is based on the understanding that schools are communities in which children develop from infancy to adolescence in a cohort with their peers, and in partnership with parents and carers. Schools need to have clear rules and expectations that are age-appropriate and focused on child welfare, and which enable the school to operate fairly and safely. Schools need to ensure that equality and anti-bullying policies (including the recent enthusiasm for all things rainbow) do not inadvertently undermine safeguarding, or isolate children from their parents or put them at risk.

Our guide aims to provide whole-school rules that are fair and safe for everyone.

The EHRC has historically been wedded to the idea that, when it comes to people who identify as transgender, you can’t have clear rules, but must instead carry out individual, or case-by-case, assessment (sometimes it caveats this with “often” or “sometimes”). It successfully defended that principle at the permission stage in the AEA v EHRC application for a judicial review, although that case does not provide a precedent that binds any other.

The relevant section of the Statutory Code of Practice for service providers states that:

“Service providers will need to balance the need of the transsexual person for the service and the detriment to them if they are denied access, against the needs of other service users and any detriment that may affect them if the transsexual person has access to the service.”

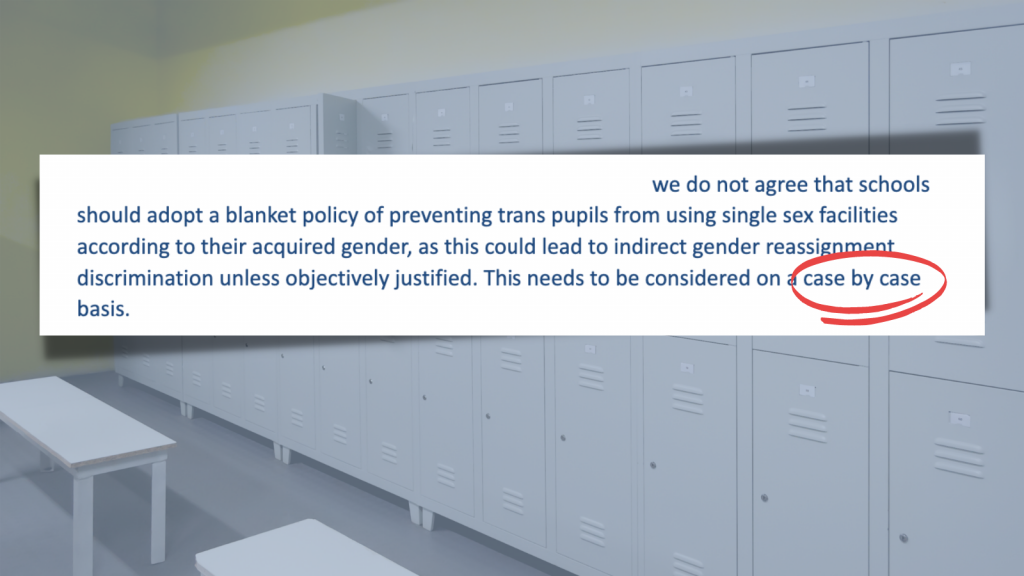

This is what the EHRC points to when they say that individual “case-by-case” assessment is needed. In its email to us in May 2021, it said:

“We do not agree that schools should adopt a blanket policy of preventing trans pupils from using single-sex facilities according to their acquired gender, as this could lead to indirect gender reassignment discrimination unless objectively justified. This needs to be considered on a case by case basis.”

In this it was agreeing with the lobby group Mermaids, which argues:

“The term ‘a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim’ is not a blanket rule and cannot be applied as a matter of policy. It is intended solely in respect to the impact of one individual by another individual in that specific situation at any given moment in time.”

We think this approach is unworkable, unfair to all the children involved and based on a misunderstanding of the Equality Act 2010. As Lord Reed said in a case about social welfare benefits, the use of rules may be not only justifiable but necessary:

“Those who criticise rules of general application commonly refer to them as ‘blanket rules’ as if that were self- evidently bad. However, all rules of general application to some prescribed category are ‘blanket rules’ as applied to that category. The question is whether the categorisation is justifiable.”

He notes that

“[…] the case law of the Strasbourg court has always recognised that the certainty associated with rules of general application is in many cases an advantage and may be a decisive one. It serves ‘to promote legal certainty and to avoid the problems of arbitrariness and inconsistency inherent in weighing, on a case by case basis’.”

A similar speech could have been made by any headteacher explaining to pupils and parents why every child must follow rules that are there to keep everyone safe, and to avoid problems of arbitrariness and inconsistency in expectations and school discipline.

The EHRC has failed to identify criteria for individual case-by-case assessment

The EHRC has never said what might go into an individual case-by-case assessment. In schools, unlike some adult settings, there is no uncertainty about the sex of the service users. If there are criteria other than sex that can be applied to govern access to single-sex facilities, the EHRC has not succeeded in coming up with them after four years of work and hand-wringing.

For example, a school cannot have a policy that would:

- allow a feminine-looking boy who identifies as a girl to use the girls’ showers, while prohibiting another boy with a more masculine build and manner from doing so

- allow boys who identify as girls to use the girls’ facilities only if they have long hair and when wearing a skirt

- allow a boy who identifies as a girl to use the girls’ facilities at age 11, but withdraw that permission at age 13 as the cohort grows up

- make access to opposite-sex facilities contingent on a medical assessment, diagnosis of gender dysphoria or medical treatment (since the protected characteristic “gender reassignment” does not rely on a medical assessment)

- expect teachers to decide on any given day whether the particular group of girls that will be forced to share facilities with a particular male child will suffer a greater detriment than on another day, or than another group of girls

- ask or encourage girls to consent to undress with a male peer.

It cannot truthfully tell pupils and parents that the girls’ showers are female-only while sometimes allowing a male student to share them. It cannot share with other parents any personal details about the male child whom they are allowing into the girls’ facilities. So it would need to tell all parents that all facilities may be mixed-sex at any time. It would then need to reconcile this with regulations relating to school premises that require single-sex facilities to be provided for all children aged eight and over, and also to consider the equality impacts on other protected characteristics.

These examples also apply to girls who identify as boys and want to use boys’ changing rooms, toilets and showers. The boundaries and bodily privacy of all children matter.

The EHRC lost sight of reality

The EHRC would make some progress towards giving clear guidance if it would remember that the Equality Act does not change people’s sex.

The technical guidance in some places seems to be written by a visitor from a post-modern fantasy world in which words override reality. It refers to a “previously female pupil”.

This is magical thinking that has no place in guidance for any institution with a responsibility for safeguarding. A female pupil who declares a trans identity remains female, and the school has a duty of care not to indulge a fantasy that would mean exposure to risks that other female pupils would be protected from. Female pupils can get pregnant. Female pupils should not undress in spaces exposed to male pupils and staff. There is no such thing as a “previously female pupil”, either in reality or legally (the Gender Recognition Act, which allows some people to change their legal sex, applies only to over-18s).

The EHRC became a little clearer about this in 2018, issuing a statement which clarified that:

“In UK law, ‘sex’ is understood as binary, with a person’s legal sex being determined by what is recorded on their birth certificate.”

This should be straightforward for schools, where every child is known and registered, and no child will have a Gender Recognition Certificate to change their legal sex. (It might be possible in theory for an 18-year-old to get a GRC before leaving school, but it is vanishingly unlikely.)

Case-by-case assessment is not a workable policy

We do not think it is possible to produce guidance and workable policies that enable schools to apply individual case-by-case assessments in order to allow some children who identify as trans to use opposite-sex facilities and not allow others. If it were, the EHRC would have done it by now.

In the AEA v EHRC case, the only example the EHRC could come up with of a situation where it might be appropriate to admit a trans-identifying male to a women-only refuge was strikingly implausible: a “trans woman” (and “her child”) being admitted to a completely empty women’s refuge.

When the Sports Councils looked at this question seriously, in relation to fairness and safety in sport, they found that “‘case-by-case’ assessment is unlikely to be practical nor verifiable”.

“Case-by-case analysis may fall outside of the provisions of the Equality Act (whereby provision is for average advantage not individual advantage) and may be based on criteria which cannot be lawfully justified. Some transgender people will be included, some will be excluded through criteria outside of their own control.“

As we say in our guidance, the demand for case-by-case assessment is not only unworkable, it is a misunderstanding of what the Equality Act requires as “objective justification”.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission explains that the objective justification relates to policies:

- The aim must be a real, objective consideration, and not in itself discriminatory (for example, ensuring the health and safety of others would be a legitimate aim).

- The importance of the aim must outweigh any indirect discriminatory effects.

- There must be no alternative measures available that would meet the aim without too much difficulty and would avoid such a discriminatory effect: if proportionate alternative steps could have been taken, there is unlikely to be a good reason for the policy.

This means that what must be justified is the rule or policy, not each individual decision to require a given child to follow the rules on any particular day.

Changing rooms and other single-sex facilities

The Equality Act requires, and the DfE strongly emphasises, that schools should segregate the sexes only where doing so is objectively justified. In a mixed-sex school you cannot arbitrarily separate girls and boys into different classes, but you can separate them into different rooms for changing, washing and using the toilet. That is because the need for privacy and dignity, and to avoid opportunistic sexual harassment, constitutes objective justification for the policy. Single-sex facilities also make it possible for female staff to supervise girls, and male staff to supervise boys, which is good practice.

A policy of allowing some male teenagers to change and shower in female facilities, and vice versa, would destroy the ability of the changing-room policy to meet its original aims. And these aims were the objective justification for the separate-sex facilities in the first place.

The EHRC’s argument is that schools and other institutions cannot have blanket rules that prevent children using opposite-sex facilities as this might result in indirect discrimination, since these rules are a detriment to children who identify as transgender.

We disagree with its analysis. Firstly, it is not obviously the case that it is in a child’s best interests to encourage them to believe they should live their lives as the opposite sex. The majority of gender non-conforming children who adopt a cross-sex identity will grow out of it, if they are not prematurely socially transitioned and then put on puberty blockers and hormone treatments. Many parents disagree with the rush to transition their gender non-conforming and troubled children.

As the Bayswater support group of parents wrote to the EHRC in September 2020:

“Parents in our group tell us that secondary schools struggle to situate their children’s gender problems in any context but gender identity, as if transition were a catch-all solution rather than a fresh signal of a child’s distress about traumatic changes in adolescence. You’ll be aware that many children who repudiate their bodies also struggle with broader identity confusion than just gender. Our children’s mental health issues and developmental differences make them authentically non-conforming in ways that may not fit the prescriptive models of difference which schools promote. Often there are clear signs that society has signalled to a child that he or she is unacceptable in some way, and the trans identification can be a way for the child to render that difference acceptable. As parents, we seek to understand what problems our children are seeking to solve in proposing body modifications but too often we find schools have no curiosity for such important questions. This is a highly sensitive and little understood area of children’s development, in which – inevitably – secondary schools are ill-equipped to intervene.”

Secondly, schools have a responsibility to safeguard all children and not to force, shame, coerce or trick them into undressing with members of the opposite sex.

Finally, as we argue above, schools need to have workable rules that can be communicated and applied fairly. A girls’ changing room that may at any time include a male child (with girls and their parents not being told, or girls being expected to pretend they don’t know) is no longer a place where girls can change in confidence (including but not limited to Muslim girls, Sikh girls Jewish girls, girls who have been sexually assaulted, etc).

We do not completely dismiss the EHRC’s point about indirect discrimination. A school should consider whether its policy and provision of separate-sex changing facilities cause discomfort to a child with gender dysphoria, and whether there is a less discriminatory overall set of policies that could be applied. But this does not require the school to allow a child to change with the opposite sex.

As we say in our guidance:

“An alternative policy such as ‘in addition to male and female changing rooms, there is a unisex option’ would still meet the aim of allowing girls and boys to have normal bodily privacy, and would alleviate the distress that a child with gender dysphoria may feel.”

This is very close to what the EHRC says in its Technical Guidance for schools, which includes as an example of indirect discrimination:

| A school fails to provide appropriate changing facilities for a transsexual pupil and insists that the pupil uses the boys’ changing room even though she is now living as a girl. This could be indirect gender reassignment discrimination unless it can be objectively justified. A suitable alternative might be to allow the pupil to use private changing facilities, such as the staff changing room or another suitable space. |

It does not state that a suitable alternative would be for a male student to share the female changing rooms (or vice versa). Nor do we. This would be inappropriate.

Names and pronouns

On names, the Technical guidance says:

| A previously female pupil has started to live as a boy and has adopted a male name. Does the school have to use this name and refer to the pupil as a boy? Not using the pupil’s chosen name merely because the pupil has changed gender would be direct gender reassignment discrimination. Not referring to this pupil as a boy would also result in direct gender reassignment discrimination. |

While we think that the EHRC’s characterisation of a female pupil with gender dysphoria as a “previously female pupil” is irresponsible and inaccurate, we agree with its guidance that it would be direct discrimination to allow some children to change their names but not allow others to do so. Our guidance says:

“Many schools allow pupils to use informal forenames (nicknames or shortened versions) chosen by pupils, even if these differ from what is recorded on their birth certificate. Schools should not discriminate in this policy, but should allow it for all pupils (within reasonable limits; such as that children cannot ask to be called something different on a weekly basis). A child should not be limited to adopting a name stereotypically associated with their sex.”

The technical guidance does not give direct guidance on pronouns, but it does say that there are situations in which a female pupil should be “referred to as a boy”. We do not think this can be derived from the law on direct discrimination in the same way as allowing all children to change their “known as” name (if this is the school’s general policy).

Schools do not have general policies of allowing children to lie, or of colluding in lying about or to children. This is particularly so when it comes to sex, because being truthful, and not keeping secrets with children about sex is important for safeguarding. Referring to a girl as a boy, or a boy as a girl, is a lie that could put that child and other children in danger. It undermines safeguarding.

It is neither direct or indirect discrimination for a school to refuse to collude in lying about or to children, or to parents. In fact, it is direct discrimination to apply less robust standards of safeguarding to a child who declares themselves to be trans (or lesbian, gay or bisexual, for that matter).

The Technical guidance gives another example that touches on pronouns:

| A member of school staff repeatedly tells a transsexual pupil that ‘he’ should not dress like a girl and that ‘he’ looks silly, which causes the pupil great distress. This would not be covered by the harassment provisions, because it is related to gender reassignment, but could constitute direct discrimination on the grounds of gender reassignment. |

This example conflates a number of different issues. Should a staff member tell a child they should not dress like a girl? A staff member should apply the school uniform rules fairly and without favour. Some schools have a single uniform code for girls and boys. Some have male and female uniform policies that are not identical. In any case, it is the policy or rule that would need to be tested, not the fact that the teacher applied it. Should a staff member tell a pupil they look “silly”? Probably not. Should a staff member avoid calling a male pupil “he”? There is no specific case law on this, but by bundling it up with calling a child silly and the ambiguous treatment of the school uniform rules, the EHRC seems to be making a moral case that this is bad behaviour by the staff member.

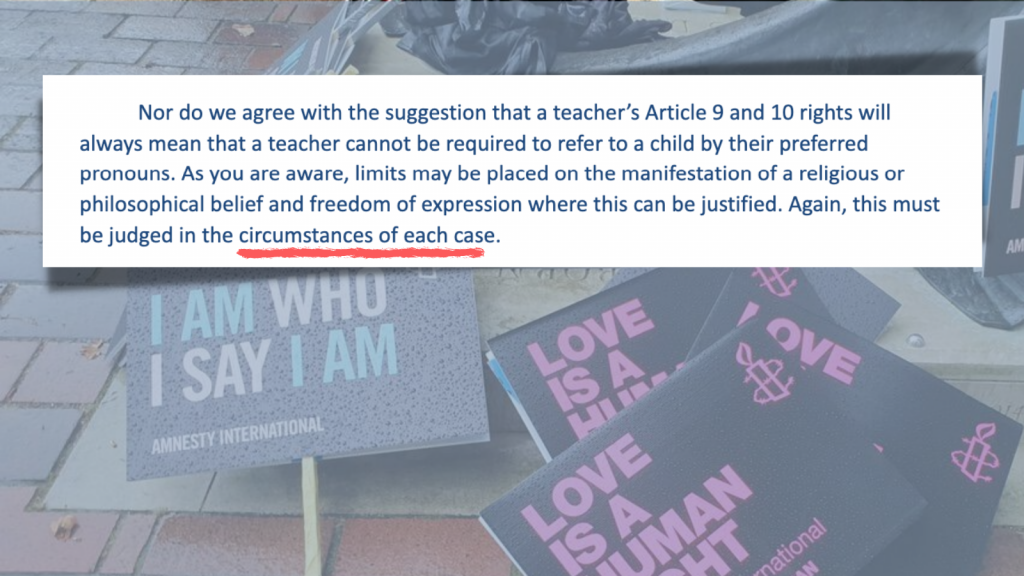

In their letter to us they say that schools should have policies on enforcing pronouns on a case-by-case basis, but again they do not say what the criteria should be. How can a school say it will force members of the school community to use preferred pronouns for some pupils but not others?

Our guidance says:

“Schools should make clear that they have responsibilities for the freedom of speech, and freedom of religion and conscience, of all pupils, as well as for the particular needs of children with special educational needs and disabilities, when responding to a request by a child to be referred to by pronouns denoting the opposite sex. Children should be encouraged to treat each other with kindness and respect, but teachers should remember that this principle extends to refraining from seeking to impose counterintuitive language on other children.”

Many parents are concerned about schools relying on EHRC guidance for their policy of “affirming” pupil’s adoption of a cross-sex identity, often behind parents’ backs or without their permission. This is a serious psychosocial intervention in a child’s life.

We were recently sent some correspondence with the EHRC by a parent who had raised this and challenged the example in the Code of Practice. Notably, the EHRC defended the guidance on names, but glossed over the question of pronouns:

“The example is given as an illustration of what might amount to direct discrimination. It is considering a situation where a young trans person has begun to live in their acquired gender and has changed their name. If a school were to refuse to use the young person’s new name because they were trans, when they did allow changes in name for other reasons, then that would be direct discrimination, as the young person would be being treated worse than others because they are trans.”

The EHRC may perhaps be backing away from its previous advice on pronouns in this recent correspondence. In its earlier letter to us, it says the issue must be considered on a case-by-case base. But in the AEA case, it seemed to be advocating a “blanket” approach. In its skeleton argument, it said:

“It should not be contentious that service providers should generally respect the gender identity of a trans-person, for example by using their preferred pronouns and chosen name.”

In fact, as many parents tell us, it is very contentious that schools are socially transitioning children (including vulnerable children) behind parents’ backs, without medical supervision, after the child has declared they are trans with the encouragement of peers and online communities. This is not simply a question of respect.

Where does the EHRC get the idea that a school should respect the self-diagnosis of an underage child as a transsexual – and that this means it must compel adults and other children to pretend that child is the opposite sex, defying basic safeguarding?

One clue comes in its 2014 guidance, What equality law means for you as an education provider: schools, which appears to be an earlier version of the example in the Technical Guidance. It states:

A 16-year-old pupil is diagnosed with gender dysphoria. The pupil has adopted a male name by Deed Poll. The school allows a change of name in its records but refuses to use any male pronouns with regard to this pupil. This greatly distresses the pupil. Such treatment is likely to amount to direct discrimination because of gender reassignment.

Below this it states “(Example provided by Gender Identity Research and Education Society.)”

So yes, our guidance departs in some respects from the examples used in EHRC’s Technical Guidance, which appear to have been derived from transgender lobby groups and are in places plainly wrong. Instead, our guidance cleaves to the Equality Act 2010 and the principles of safeguarding.

The EHRC’s advice is inconsistent and, we argue, in many cases unworkable and incompatible with safeguarding or the Equality Act.

Summary

| What our guidance says | What the EHRC Technical Guidance says (2014) | What the EHRC says in its letter of 5 May 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treating a child as if they were the opposite sex | This is not compatible with safeguarding. Do not lie or keep secrets about sex with or about children. | It would be direct discrimination not to treat a child as if they have changed sex. | |

| Changing rooms/toilets etc… | Consider offering a unisex alternative for a child who is distressed by same-sex facilities. | Consider offering a unisex alternative for a child who is distressed by same-sex facilities. | Do not adopt a blanket policy of not allowing children to use opposite sex facilities. The issue must be determined on an individual case-by-case basis. |

| Names | Treat all children who wish to use a “known as” name similarly, otherwise it may be direct discrimination. | Treat all children who wish to use a “known as” name similarly, otherwise it may be direct discrimination. | |

| Preferred Pronouns | Protect children from bullying, but you cannot compel others to undermine safeguarding, or express beliefs they don’t share. | Nothing clear | Whether someone is allowed to use accurate sex-based pronouns must be determined on an individual case-by-case basis. |

How can the EHRC and the DfE put this right?

Until 2021 the EHRC was a Stonewall Champion. Until 2020 it was led by a previous Chair of Stonewall, and it has had a close relationship with Stonewall, Mermaids, Gendered Intelligence and GIRES. Meanwhile the Department for Education was led by Stonewall “Senior Champion” Jonathan Slater, whom Stonewall celebrates as “the first Permanent Secretary to attend the Stonewall face-to-face feedback meeting to hear first-hand about how the department might build on the positive work that has already been started, learn about best practice and lead change”.

These public bodies must go back to the Equality Act 2010 and case law, taking account of the fact that safeguarding is an overriding objective for schools and that parents should be involved in any serious decision a school makes about a child.

They must listen to parents who report that the Equality Act guidance is being used to justify schools socially transitioning confused, non-conforming, vulnerable, traumatised and autistic children, without either parental consent or a mental-health diagnosis, in order to win Stonewall points. This was never the intention of the guidance.

The EHRC rightly tells concerned parents that S.7 of the Equality Act, which defines the “transsexual” protected characteristic, is widely drawn. A school cannot exclude a child from protection against discrimination on the basis of gender reassignment because they don’t have a gender dysphoria diagnosis, haven’t told their parents, have other conditions or have a history of trauma. The Equality Act simply does not allow them to do that.

Where EHRC has gone wrong is in repeating the assertion of the lobby groups that if someone is protected by S.7 of the Equality Act, this means that rules which apply to people of their sex do not apply to them, and that other people are obliged to pretend they are the opposite sex.

That is not what the Equality Act requires. The Equality Act requires that people with a protected characteristic (or who are perceived to have one) are not excluded from, harassed or discriminated against in employment, education or as consumers because of that protected characteristic.

The Equality Act is being used in ways that were never intended, and the consequences are to harm children and to undermine safeguarding. Individual case-by-case assessment is clearly no basis for workable policies. The EHRC has left schools without clear, workable guidance for too long.

| This is the guidance that the EHRC and the Department of Education should urgently provide to schools. A child who declares themselves to be trans, or is perceived to be trans, is protected by S7. of the Equality Act. They should not be discriminated against in education. This means they should be able to access lessons and exams, sports and swimming lessons, school leadership positions, school trips and every aspect of school life, just like any other child. But their sex has not changed. There are a few situations where sex matters, and schools should make sure that such a child is not bullied in or excluded from facilities appropriate to their sex. Schools should also consider whether it is proportionate to have a policy of offering alternative unisex provision, in addition to single-sex facilities, in order to facilitate inclusion. |