For Women Scotland in the Supreme Court

What was the case about?

For Women Scotland Ltd v The Scottish Ministers was heard by the Supreme Court on 26th and 27th November 2024. It concerned the effect of the Gender Recognition Act 2004 on the definition of “woman” and “man” for the purposes of the Equality Act 2010.

It focused on statutory guidance issued by the Scottish government under the Gender Representation on Public Boards (Scotland) Act 2018, which sets targets for increasing the proportion of women on public boards in Scotland. The guidance, which is required to be in line with the Equality Act 2010, states that “woman” includes a person whose “acquired gender is female” under the Gender Recognition Act.

The grassroots organisation For Women Scotland (FWS) challenged that guidance in the Scottish Court of Session, and lost. That, in effect, removed the category of biological sex as a protected characteristic from the Equality Act, ruling that references to “male” and “female” should be taken to refer to sex as modified by a gender-recognition certificate (GRC).

What was the case not about?

The case had nothing to do with gender self-identification – that is, the idea that people are the sex they say they are. The question under consideration concerned only the classification of the 8,000 or so people who have GRCs. (It had already been established that for the purposes of the Equality Act and all other laws, people who identify as the opposite sex, or as non-binary, remain legally of their biological sex.)

It did not directly relate to the separate protected characteristic of gender reassignment, which protects people with trans identities from discrimination and harassment in employment and a range of everyday situations. Having this protected characteristic does not change a person’s sex for any legal purpose.

It will not lead to a decision on how the Gender Recognition Act interacts with any law other than the Equality Act 2010 (although depending on the reasoning in the eventual ruling, the outcome may affect the interpretation of other laws where the meaning of “sex” matters).

Who were the parties?

The appellant was For Women Scotland, a grassroots group of campaigners for sex-based rights led by Marion Calder, Trina Budge and Susan Smith. The respondent was the Scottish government.

Who were the intervenors?

Several individuals and organisations applied to be allowed to submit written interventions arguing for one side or the other. Those that were accepted were:

- in support of the Scottish government’s position that “sex” in the Equality Act 2010 must be taken to mean “sex as modified by a gender-recognition certificate”, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC; the national equality watchdog) and Amnesty International UK

- in support of FWS’s position that “sex” in the Equality Act 2010 must be taken to have the common-law, biological meaning, Sex Matters and a coalition of three organisations representing the rights of lesbians – Scottish Lesbians, the Lesbian Project and LGB Alliance.

As the parties to the case, FWS and the Scottish government were given several hours each to make oral submissions. The EHRC and Sex Matters were also granted an hour each.

What were the main arguments?

What follows is very broad-brush, and intended for a general audience. We have collected links to the written submissions and several excellent legal commentaries.

The Scottish government’s argument rested on the clause in the GRA that says that when a person gets a GRC, their sex changes “for all purposes” to be the same as their “acquired gender”. The phrase “for all purposes” has already been clarified to cover only “legal purposes”, and the GRA goes on to expressly limit the “for all purposes” clause in several respects – including parenthood, sex-specific crimes and inheritance. The Scottish government argued that since the Equality Act post-dated the GRA, it must be taken to be among the purposes for which a GRC changes a person’s sex.

The EHRC’s position regarding the effect of the GRA on the Equality Act was the same. But it made much more of the serious problems this interpretation causes for the operation of the Equality Act. Its position is that, as a matter of law, a GRC changes a person’s sex for the purposes of the Equality Act, but it would be better for human rights and for the comprehensibility and operation of the law if it didn’t. It thinks that Parliament should fix the problem by expressly disapplying the GRA from the Equality Act.

Amnesty agreed that a GRC changes a person’s sex for the purposes of the Equality Act, although the organisation actually supports gender self-ID, meaning it thinks that a GRC is not necessary for someone to count as a member of the opposite sex, or indeed as non-binary or gender-fluid.

FWS’s central point was that the Equality Act is the law that replaced the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, in which “sex” meant biological sex and “man” and “woman” were unambiguously sex-based terms. Its written and oral submissions pointed out the serious consequences that follow from any implied change to that position, and argued that these could not have been what Parliament intended by passing the GRA.

Sex Matters agreed with the position of FWS and provided a careful textual analysis based on the principles of statutory interpretation to explain how the Equality Act and the Gender Recognition Act can be reconciled in such a way that “sex” holds its ordinary, biological meaning in the Equality Act despite the “for all purposes” clause in the GRA.

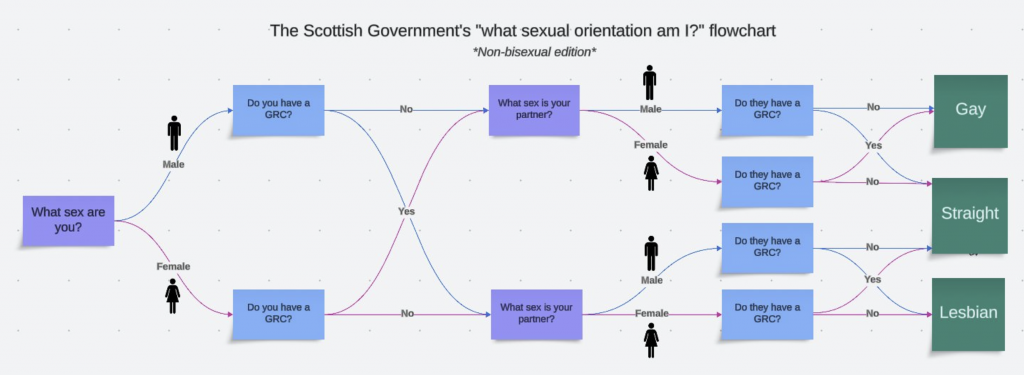

Scottish Lesbians and its partner intervenors focused on the problems caused for lesbians by interpreting “sex” to mean “as modified by a GRC”, since it means that heterosexual men with GRCs count as lesbians for the purposes of the protected characteristic of sexual orientation, as do women whose male partners hold GRCs. One practical consequence is that an association with more than 25 members cannot restrict itself solely to lesbians (in the ordinary meaning), excluding male people with GRCs, since that would count as unlawful discrimination.

What was said in court?

The two-day hearing saw the judges grapple with this and other consequences of replacing the natural categories of “male” and “female” with what might be called “certificated male” and “certificated female”.

First up was counsel for the claimant, Aidan O’Neill KC, representing For Women Scotland. He made an impassioned speech about the harms caused to women by the patriarchy, illustrating this with examples of previous laws that had denied the rights of women as a sex class. Many women watching in court and online found this very moving, though the judges appeared bemused to hear themselves accused of being too white, male, middle-class and privately educated (two of them being, in fact, women). O’Neill went on to address points of law from his written submission.

Then Ben Cooper KC, acting for Sex Matters, had an hour to lay out his legal interpretation in support of the position that the GRA could not possibly predetermine all other laws where sex matters. He walked the judges through a sex-based interpretation, illustrating how it made application of the law and prevention of discrimination at an individual and group level straightforward, and how it provides protection for everyone.

On day two, Ruth Crawford KC and Lesley Irvine, Advocate, made the Scottish government’s case for the Gender Recognition Act meaning not just that someone may be deemed to have changed sex but that they actually are that other sex. They were challenged on the implications of this. This led to at times bizarre discussions involving male lesbians and pregnant men. The judges pressed Ruth Crawford on whether the Scottish government’s interpretation meant that “pregnant men” (trans-identifying women) do not have maternity rights – yes, she confirmed that is so. At times the court struggled with language, tripping over “trans women” and “trans men” when talking about discrimination on the basis of sex and gender reassignment. The judges were aware that no surgery is required to obtain a GRC and that a person claiming to be a woman “may look like a man or like a woman”. Asked how sex-discrimination claims would work under the Scottish government’s interpretation, Crawford said she would need a flowchart, and would have to think about it over lunch.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission’s intervention was given by Jason Coppel KC, pointing out the challenges in the current interpretation of the Equality Act, which he said was certified sex, as the Scottish government claims, but which he said gave rise to serious difficulties.

The other intervenors, Amnesty International and the lesbian groups, were not given a speaking slot but the written submission made by Karon Monaghan KC on behalf of Scottish Lesbians, LGB Alliance and the Lesbian Project had a major impact on day two. Questioned by the judges, Ruth Crawford confirmed that the Scottish government’s interpretation means that there are male lesbians, and that female lesbians cannot lawfully form an association that excludes them. Her proposed solution was that such lesbians could form an association of “gender-critical lesbians”, relying on the Forstater ruling.

The consequences of the Scottish Government’s legal interpretation for sexual orientation are shown in the graphic below.

Finally, Aidan O’Neill for FWS did a brief summing-up in which he challenged points made by every party. He also pointed out the inconsistency of the Scottish government’s claim that sex can only be biological sex in a statute which explicitly says that the GRA does not apply, since the fight in Holyrood over Johann Lamont’s six-word amendment to the Forensic Medical Services (victims of sexual offences) Scotland Act 2021 was about replacing “gender” with “sex”, clearly relating to biological sex, but with no disapplication of the GRA.

Does this case matter beyond quotas on public boards in Scotland?

Yes. The details of Scotland’s devolution settlement and the provisions for “positive action” in the Equality Act mean that the definition of “woman” in the Gender Representation on Public Boards (Scotland) Act 2018 must precisely match the meaning of “woman” in the Equality Act. This case will therefore settle that meaning not just in Scotland but across the UK, and not just when it comes to quotas for public boards but across the Equality Act.

When will we know the outcome?

We don’t have a firm date, but certainly not before Christmas. Our best guess is February or March.

What are the possible outcomes?

The Scottish government wins.

The meaning of “sex” in the Equality Act is fixed as “sex as modified by a GRC”. This means, among other things, that commissioning and planning a genuinely single-sex service becomes extremely difficult, since an equality impact assessment will never consider the needs of (biological) women as distinct from (biological men) – in particular, it will never be able to consider whether outcomes for women are harmed by including men with GRCs stating their sex as female.

The Scottish government wins, but…

The judgment of the Scottish Inner Court against which FWS was appealing held that the meaning of “sex” could vary throughout the act, with the default being “sex as modified by a GRC” and the natural meaning of sex substituted when any other reading would be absurd. This was a surprising ruling, since core terms listed in a law’s “definitions” section are generally held to have a single, fixed meaning throughout. Nevertheless, it is not impossible that the Supreme Court could decide something similar.

Another possibility is that the Supreme Court agrees with the Scottish government that “sex” in the Equality Act as it stands means “as modified by a GRC”, but that it shouldn’t. It could say that the two laws together create a terrible muddle that it falls to Parliament to fix.

FWS wins, and “sex” in the Equality Act takes its natural meaning.

What next?

If FWS wins:

The Scottish government will have to amend the Gender Representation on Public Boards (Scotland) Act 2018 to make clear that “women” does not include men with GRCs.

The EHRC will need to rewrite its guidance on single-sex services to remove all the complications concerning GRCs.

Sex Matters and other campaigners will seek to ensure that all guidance from government and publicly funded bodies makes clear that the protected characteristic of “sex” refers to the natural meanings of male and female, and that this cascades through to the public-sector equality duty and all public funding.

If the Scottish government wins:

It may be open to FWS to take an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights. It has not said whether it is considering this option.

In any case, this is not the end of the road for campaigners seeking to establish the natural meaning of sex in law and life. The next steps concerning the GRA and the Equality Act could be political or legal, depending on the judgment.

For Sex Matters, the immediate next legal battle will concern a different law: the Police And Criminal Evidence Act (PACE), which among other things sets out the rules for searching of detainees. We are preparing to take legal action against British Transport Police, which says that a male police officer with a GRC stating his sex as female is able to search female detainees. We say this is a contravention of PACE, which requires same-sex searching, and of women’s Article 3 rights in the European Convention on Human Rights to be protected from inhuman and degrading treatment.