There’s still a fatal flaw in the government’s digital trust framework

The Office for Digital Identities and Attributes last week published the latest version of the UK digital identity and attributes trust framework (0.4).

But it has still not recognised the problem of inaccurate sex data provided by the public authorities that underpin the system.

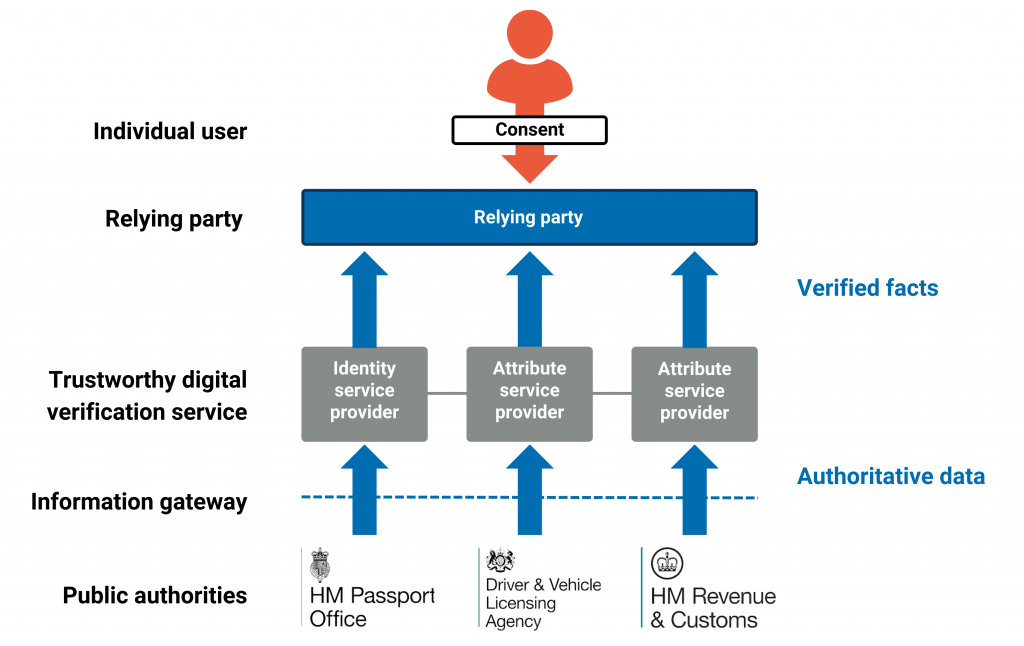

The trust framework is a set of rules for an organisation to follow if it wants to have its service certified as a trustworthy digital verification service (DVS). A DVS is a service that enables people to digitally prove who they are: information about themselves or their eligibility to do something.

DVS providers can have their services independently certified against these rules to prove they meet the high standards set out in the trust framework.

The system is designed so that its integrity rests on data from public authorities such as HM Passport Office, the Driver & Vehicle Licensing Agency, NHS bodies and HM Revenue & Customs.

The framework tells service providers (at 7.1.b) that they must make clear to relying parties and users whether an identity or attribute they hold comes from a certified or uncertified service, “except where it comes from a UK government source”. Information obtained from government sources (whether through hard-copy documents such as passports, or digital information passed through the planned “information gateway”) is assumed to be accurate and reliable.

“Authoritative” government data has been corrupted

The big problem is that no standards àre set for the data from public authorities, and we know that the public authorities do not meet the standards that are being set for private-sector providers.

The framework says that to be certified as trustworthy, service providers must have a management system that ensures integrity of data (at 11.6.1). This includes having controls that:

- stop information from being modified, either by accident or on purpose

- provide assurance that information is trustworthy and accurate

- keep information in its “correct state” – the format or reason for collecting the information must not change

- restore information to its correct state if it is suspected to have been tampered with.

So for example if an organisation knows that a user is male and has this data stored, it would not be compliant with the trust framework to change that information from “male” to “female”. Nor would it be compliant to provide data on any user’s sex without being able to provide assurances that this information is trustworthy and accurate (it is not enough to say that the majority of records are accurate).

It is also not compliant with the rules to mix up categories of data. An attribute recording “sex” is different from the legal category of “sex as modified by a gender-recognition certificate”, and different again from “gender identity”. Labelling the attribute “gender” and being vague about what this means is not good enough.

But the Passport Office, the DVLA and the NHS do this all the time. As our report Sex and the Data Bill – beware of building digital identities on sand sets out:

- over the past five years at least 3,188 passports have been changed to show the wrong sex.

- over the past six years at least 15,481 driving licences have been changed to show the wrong sex.

- a person’s recorded sex can be changed on request in NHS records, after which a new NHS number is issued, and it is not known how many records have been changed.

None of these changes require that a person has a gender-recognition certificate, and individuals may be recorded with a different sex (and in some cases a gender identity such as “non-binary”) by different government bodies.

Having “authoritative” sources for data which disagree with each other about an attribute which is in reality immutable is a significant flaw in the system. It will cause problems for people with inconsistent records (those who identify as transgender), for anyone who wants to be able to attest their own sex accurately and for anyone who wants to rely on that data.

The system is flawed from the start

This problem means that data-protection principles are being flouted from the very foundation of the DVS system. Mixing up concepts of immutable, objective sex and mutable, subjective gender identity makes it impossible to meet the requirements set out at 12.7.3 of the framework about consent to share data.

The framework says (at 12.7.3.b) that when confirming understanding a service provider must:

- use clear, plain language that is easy to understand

- ask the user to positively confirm their understanding

- specify why they or others in their supply chain are processing the data and what they are going to do with it

- record when and how a user confirmed their understanding, and what they were told at the time.

None of this can be done if the service provider is not clear whether the data they are processing is sex (male or female, a fact that cannot change) or “gender identity” (a subjective idea), or “mostly sex but sometimes sex as stated on a gender-recognition certificate”.

The government itself is not clear about this in its own “authoritative” sources. The word “sex” does not appear in the trust framework at all, even though it is an important part of a person’s foundational identity recorded on the birth register, and a piece of information that is often needed for practical purposes.

At 2.1.3.c the framework gives examples of attributes that a “relying party” (such as a potential employer) might need to know to find out if a person is eligible to do something. It lists for example their nationality, address, qualifications or… “gender”.

But “gender” (apart from when it is a synonym for sex) is something that cannot be verified. It is, as defined by its advocates, a subjective feeling that may shift from day to day. It is not clear that a person’s subjective feelings about gender identity (or their performance of sex stereotypes) could be a factor that makes them eligible or ineligible for any particular service.

The Data (Use and Access) Bill which will provide the statutory basis for DVS system is going into committee stage in the House of Lords this week.

Lord Arbuthnot and Lord Lucas raised the issue of inaccurate and unreliable sex data during the second reading, but their concerns were dismissed by the government. There is an opportunity now for the government to recognise that these issues are real. Lords Arbuthnot and Lucas have tabled amendments (34, 48 and 200) to draw attention to this critical flaw in the system and to try to close the loopholes in order to ensure that the system is able to provide accurate, trustworthy information on sex.