UN special rapporteur calls for sex screening in women’s sport

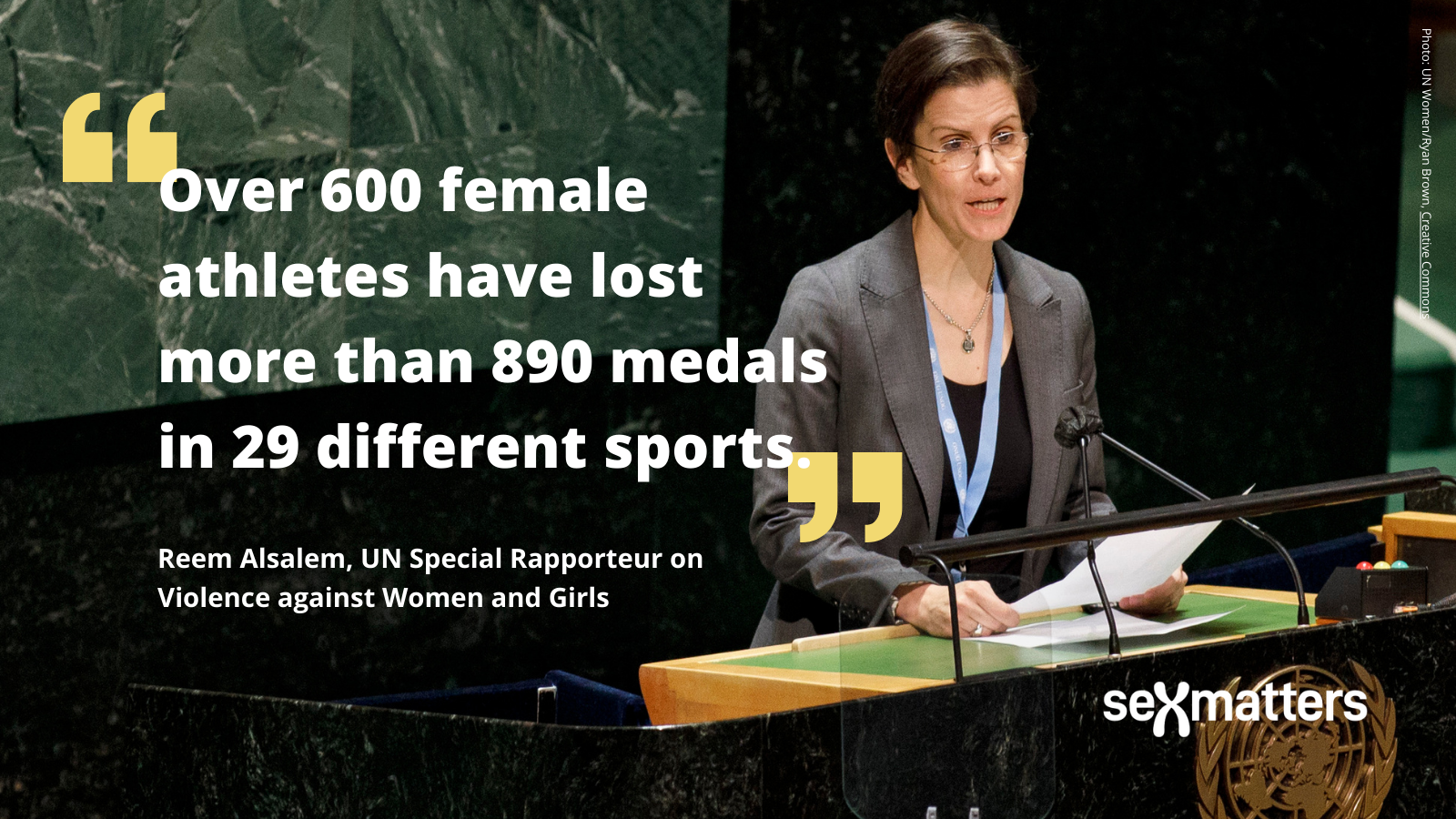

The UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women and Girls, Reem Alsalem, has published her report on violence against women and girls in sport. Together with her team, she took evidence in writing and in person, including meetings with Sex Matters and other groups in the UK. In her report, presented to the UN General Assembly on 8th October, she says that a protected female category is needed to ensure safety and fairness in sport at all levels. She sets out a range of adverse effects of male inclusion in women’s sport, including that governing bodies’ failure to exclude men from women’s competition has so far led to more than 600 female athletes losing 890 medals in 29 different sports. This is likely to be a substantial underestimate.

Alsalem’s recommendations include a call to ensure that “female categories in organised sport are exclusively accessible to persons whose biological sex is female”. To this end, she calls for the return of sex screening, noting that at the last Olympic Games to have sex testing, in Atlanta in 1996, most female competitors wanted it to continue.

The report says:

“In cases where the sex of an athlete is unknown or uncertain, a dignified, swift, non-invasive and accurate sex screening method (such as a cheek swab) or, where necessary for exceptional reasons, genetic testing should be applied to confirm the athlete’s sex. In non-professional sports spaces, the original birth certificates for verification may be appropriate. In some exceptional circumstances, such tests may need to be followed up by more complex tests.”

If the International Olympic Committee (IOC) had followed this protocol, it would have avoided the debacle in women’s boxing at the Paris Games in August, and protected all those affected. Either the two boxers at the centre of the row, Imane Khelif and Lin Yu-Ting, would have demonstrated they were female and eligible, or they would have been excluded before the first bout.

Alsalem lays out the impact of her recommendations on athletes who may have a disorder of sex development. Sports bodies shouldn’t subject anyone to invasive sex screening, she writes, and shouldn’t force anyone to lower testosterone levels to compete in any category. Sport can be made fully inclusive without such measures, she points out, either by creating new open categories for people who do not wish to compete in the category of their biological sex or by converting the male category into an open category.

The IOC opposes sex screening, favouring self-declaration supported by passports. But the international federations for the three largest Olympic sports, athletics, cycling and swimming, have already protected their female categories and adopted open categories to ensure fair, safe sport for women and girls, just as Alsalem recommends. Several other sports in the UK and internationally have also done so.

The biggest sport that is still failing to protect its female players is football. The international body, FIFA, and the UK bodies, the FA, Scottish FA and FA Wales, have been reviewing their policies for some time. Meanwhile, male players are widely reported across women’s football, including in women’s professional soccer in the USA. As football is a contact sport, this creates problems for safety as well as fairness.

UK reports have shown how one male player can affect numerous women and girls. The FA currently allows male players into women’s football if they suppress their testosterone, a medical intervention Alsalem rejects as both invasive and ineffective.

The FA has approved 72 trans-identifying male players to compete in women’s football in England, up from 50 when the policy review began two years ago. Its then-director of women’s and girls’ football, Baroness Sue Campbell, told a group of MPs at a meeting in April this year that this was a small number when compared with the number of people who play football overall – thereby tacitly acknowledging that admitting male players to female categories harms women and girls. It is unclear how many male players would have to be admitted to the women’s game before the FA thought the harm became too great to ignore.