What are the facts about applying for a GRC?

The Labour party says in its manifesto that it will:

“modernise, simplify, and reform the intrusive and outdated gender recognition law to a new process. We will remove indignities for trans people who deserve recognition and acceptance; whilst retaining the need for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria from a specialist doctor, enabling access to the healthcare pathway.”

Anneliese Dodds, Shadow Secretary of State for Women and Equalities, has described the existing process as “intrusive, outdated and humiliating”. She pledged to “remove invasive bureaucracy and simplify the process”. Stonewall call it “inhumane and undignified”

Let’s look at the facts: We have published a briefing on the evidence about how the process is working based on statistics released by HM Courts & Tribunals Service, official information and the records of the Gender Recognition Panel user group.

Too complex?

The Gender Recognition Panel process is remarkably efficient, requiring two short doctors’ reports and a handful of bank statements, payslips and utility bills. The success rate of applications for a gender-recognition certificate (GRC) is consistently 80-90%.

GRC application results and success rate

Intrusive?

There is no evidence that the current process is deterring people from applying for GRCs. Applications have soared since 2019, from around 30 a month to over 100.

Number of applications for a standard GRC

Humiliating?

The application is decided on the basis of the paperwork by a two-person panel made up of a medical and judicial member. The panel tends to take a supportive approach. If it finds that applicants have submitted insufficient evidence (such as failing to fill in the form correctly, or failing to send marriage or divorce documentation) it issues directions to enable applicants to supply the additional documentation. In 2019 Paula Gray, then President of the Gender Recognition Panel, explained the approach:

“We rarely refuse applications, and when we do it’s generally due to a consistent lack of cooperation, the applicant having been given a number of opportunities to provide the necessary documentary evidence. I probably deal with about 200 cases a year – although some are previously adjourned applications and over some 14 years I think I have refused three.”

Evidence from Gender Recognition Panel User Group meetings where trans advocacy organisations and clinicians speak freely with panel members and administrators did not describe the process as demeaning, intrusive or distressing.

Outdated?

20 years ago, when the Gender Recognition Act (GRA) was passed, it was estimated that 5,000 people identifying as transsexuals lived in the UK. Since then 8,464 certificates have been issued, over a third of those in the past four years. In 2022 the process moved online and the cost was reduced to £5. A system of “conditional refusals” was also set up to make it easier to reapply after being refused.

Applications are being submitted and GRCs awarded in greater numbers than ever before.

There is no evidence that the GRC application process is proving an unreasonable barrier to those seeking certificates. Rather, the campaign to make it easier for people to get a GRC is motivated by a desire to open up the process to those who would not currently qualify. Stonewall and allied campaigners see any requirement for medical diagnosis as “inhumane and undignified”.

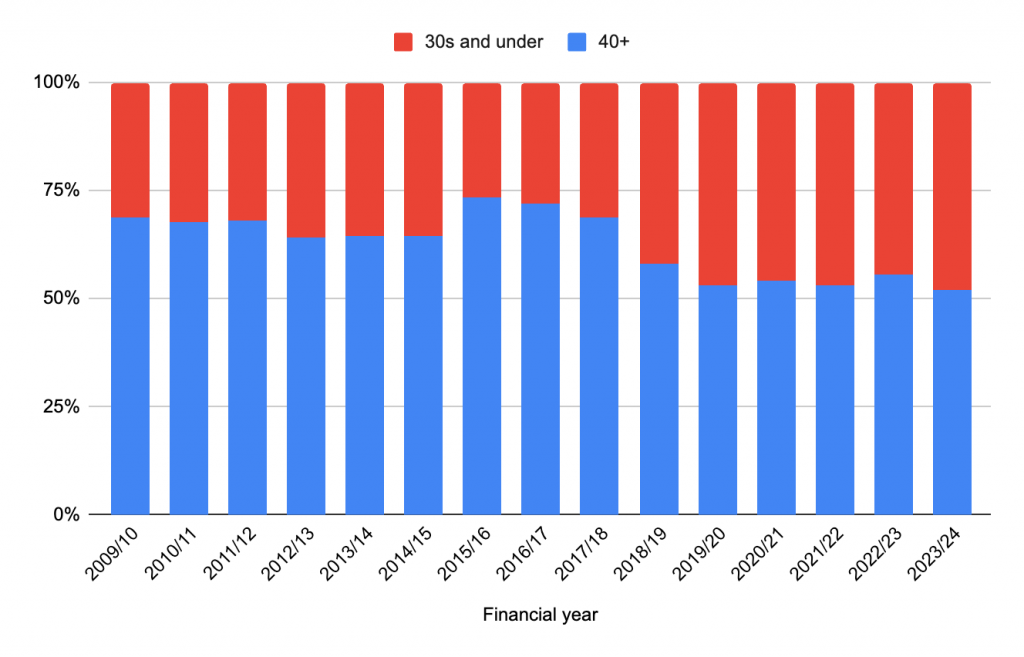

The age profile of applicants has changed, with those in their 20s and 30s rising from around 30% of applications in 2009 to around 50% in 2023/24.

Age of GRC applicants

(NB ages are estimated based on birth year bands reported by HMCTS)

And the sex mix has shifted from 80% male and 20% female to 50% male and 50% female.

Sex of GRC applicants

This pattern of sharply rising numbers, more younger people, and more “female to male” transitioners reflects and follows on from the pattern seen at the NHS Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) clinic and investigated by Dr Hilary Cass.

Adolescent referrals to GIDS and GRCs awarded

Any action to “modernise, simplify, and reform” the Gender Recognition Act should be based on evidence of how the current process is working, consideration of the problem the GRA intended to solve and recognition that other people’s rights matter. It is irresponsible to make it easier for people to change their sex for “all [legal] purposes”, as the GRA does, without considering the impact on women’s rights, child safeguarding and other areas of law and policy where sex matters.