NHS: let’s talk about sex

This tweet by Emma Parnell, Lead Service Designer at NHS Digital, and the associated Medium post “Let’s Talk About Sex” is interesting.

Parnell writes in detail about how she worked to remove the question of whether a patient is male or female from the online system for booking COVID vaccinations.

Caroline Criado Perez, author of Invisible Women, responded with dismay, saying it is important that the NHS knows the “sex & gender” of patients.

This story is both less and more than it appears. It shows why we really need to be clear about the distinction between the two concepts of sex and gender.

Sex as identity data

Understanding how sex is treated as data in bureaucratic systems is important to understand what is going on here, to work out what the problems are, and how solutions can be developed that safeguard accuracy, privacy and safety.

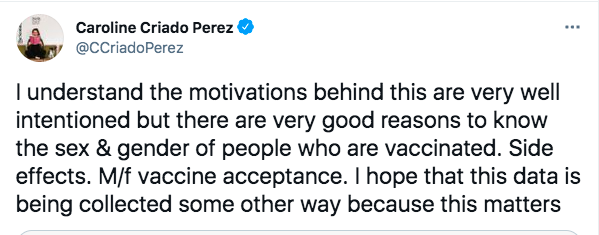

Bureaucracies use three types of information about individuals – first foundational information that establishes the unique identity of a human being. This starts with the information on the birth register that first established that identity.

Second is matching information used to link a flesh-and-blood person with the unique identity. This could be matching a photograph with a person, a signature with one on file, a pin number, or asking questions that only that person would know the answer to, or it can be done through personal recognition.

Third are functional attributes associated with that person: things that the bureaucracy needs to know about them for a particular purpose, such as to keep them safe, or to check their entitlement to a service.

Examples of the three types of personal information

All of this is your personal information and subject to privacy. Not every part of the state (or the private sector that also uses your information) needs to know everything about you all of the time.

A fourth kind of information is abstracted from your individual identity and used to generate broader statistics, to allow patterns to be studied across the population based on demographic characteristics.

Sex is both part of your foundational identity, recorded on your birth certificate, and a functional attribute – your doctor needs to know your sex for example. It is also an important piece of demographic information; those tracking who is getting vaccinated, and studying how the Covid vaccine is working need to have data on people’s sex.

Sex is also traditionally used as a piece of matching information – either formally: you are asked to fill in your name, date of birth and sex in order for the computer to find your record, or informally: the doctor’s receptionist knows that the next patient is Mrs Jean Smith, whose record says female, age 60, so they look for the older woman in the waiting room.

This use of sex as matching information is one meaning of “gender” – the doctor’s receptionist is looking for someone who appears female, not inquiring after the size of their gametes. For most people, the sex they appear to others to be (their “gender” in this sense of the word) is the same as their actual sex, and it is not particularly private or sensitive.

The Covid vaccine booking service

Parnell writes that the reason the Covid vaccine booking vaccine service was asking people’s sex (or “gender”) was as matching information – to link them to their NHS record.

They could ask people for their NHS number. But most people don’t know their NHS number, so instead the NHS has a useful system for identifying people with a combination of their name, date of birth, postcode and whether they are recorded as male or female. The vaccine booking system is an impressive piece of work which was rapidly developed and uses this system. It works well. Three cheers for the NHS Digital team.

But as Parnell says, asking for someone to fill in their sex causes problems for transgender people (including those who identify as non-binary). It causes two different kinds of problem:

- psychological discomfort about having to fill in your sex on a form when you feel dysphoria about it

- potential awkwardness if a person’s apparent sex (or “gender”) doesn’t match with their recorded sex (for example, on arrival at the vaccination centre the staff may think they are the wrong person, using someone else’s appointment).

She quotes feedback from one user of the service.

“Just thought I would let you know that we had an email from a non-binary person this week who was considering not accessing a vaccination due to having to select a binary gender option in their local system and the dysphoria this would cause.”

While your level of personal sympathy with people who don’t want to fill in their sex on a medical form in the midst of a pandemic may vary, government systems should be designed to be as inclusive as possible, and shouldn’t cause people discomfort if it can be avoided.

So is sex (or “gender”) needed as matching information?

It turns out it is not.

As Parnell highlights, it can be removed altogether from the booking system and the NHS can still identify individuals and match them to their NHS records. The other three pieces of data are enough. This is the solution they implemented yesterday.

Is this a problem?

Removing sex as matching information is not the problem that Caroline Criado Perez feared. Just because NHS don’t collect the information in order to book the appointment, doesn’t mean they don’t hold this information in people’s records.

As the NHS replied:

This solution of removing the need to use sex (or gender) as matching information is a good idea in many situations. It solves the problem of meeting transgender people’s desire not to identify publicly with their sex where it can be avoided, without corrupting the underlying data for when it is needed.

The more we shift from paper based systems to digital identity systems, the easier this approach is to implement. It keeps accurate data to be held for when it is needed, and allows people to keep it private when it isn’t. Honorifics (Mr, Mrs, Ms etc) and names can be used to indicate how people prefer to be referred to socially.

So is there a problem?

There is an underlying problem, however, with the NHS data system itself. More than ten years ago the NHS recognised that patient safety and patient-clinician relationships would be compromised if accurate records of each patient’s biological sex records were not kept. The official guidance written in 2009 explained:

“The term ‘Gender’ is now considered too ambiguous to be desirable or safe…”

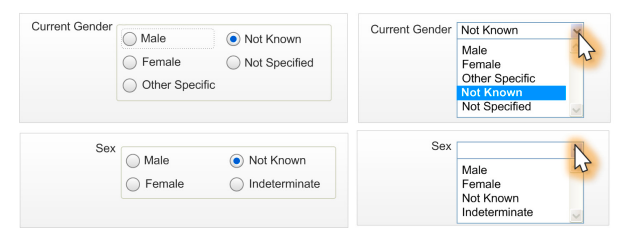

Sex and Current Gender Input and Display User Interface Design Guidance

The NHS commissioned Microsoft to design an interface system which set out separate fields and definitions for patient “sex” and “current gender”. It warned:

“Users may confuse the terms current gender and sex, or assume that they are synonymous. Therefore, it is essential that all NHS applications display and explain current gender and sex terminology and values in a clear and consistent manner.”

Sex and Current Gender Input and Display User Interface Design Guidance

The planned interface

The guidance set out in detail how to keep these two characteristics separate and unconfused. It also set out potential consequences of not adhering to these standards including:

- The patient is given the wrong treatment as a result of a failure to identify the patient correctly.

- The patient is given the wrong treatment as a result of a failure to match the patient correctly with their artefacts (samples, letters, specimens, X-rays, and so on).

- The patient is given the wrong treatment as a result of a failure in communication between staff, or staff not performing or checking procedures correctly.

- The patient is categorised with a value that cannot be utilised by any other systems.

- The patient is categorised incorrectly from a legal perspective.

- The patient is categorised incorrectly from their perspective.

But after identifying all these risks the guidance was not followed.

The current NHS data dictionary distinguishes between “phenotypic sex” (as observed by a clinician) and “patient stated gender”, but in practice only the “gender” field is consistently populated (with a person’s sex in most cases).

There are lots of parts of the healthcare system that keep patient information. The NHS Personal Demographic Service (PDS) provides the spine which enables healthcare professionals to match patients to their health records and their unique identity. It only contains “gender” which it defines as:

“The administrative gender that the patient wishes to be known as. In some cases, this may not be the same as the patient’s registered birth gender, or their current clinical gender.”

Anne Harper Wright investigated what was held in the records of the hospital where she gave birth and highlights that even here there is only gender, not sex:

We understand this is common practice.

Futhermore the General Medical Council tells doctors to change a patient’s sex/gender as recorded on medical records on request. This does not require any medical diagnosis, anatomical changes or a legal gender recognition certificate. Public Health England tells GP surgeries to change a patient’s recorded sex/gender on their medical record at any time, without requiring diagnosis or any form of gender reassignment treatment. They are given a new NHS number (a person’s NHS number codes their sex at birth: odd numbers are male, even numbers are female) and previous medical information must be transferred into a newly created medical record. They will be sent screening appointments (such as for cervical smear tests or prostate cancer screens) according to their new gender (so invitations to attend the wrong screenings).

This is a mess.

It put patients and the healthcare providers at risk. It corrupts everyone’s information (since the “gender” field doesn’t contain reliable information on sex and the sex field is left empty). And it sets up the expectation that the NHS is recording “gender”.

If the NHS tells people it records “gender” why should that be limited to male or female? Why not non-binary? And why not genderfluid, demiboy, genderqueer or any number of other options?

The trick question

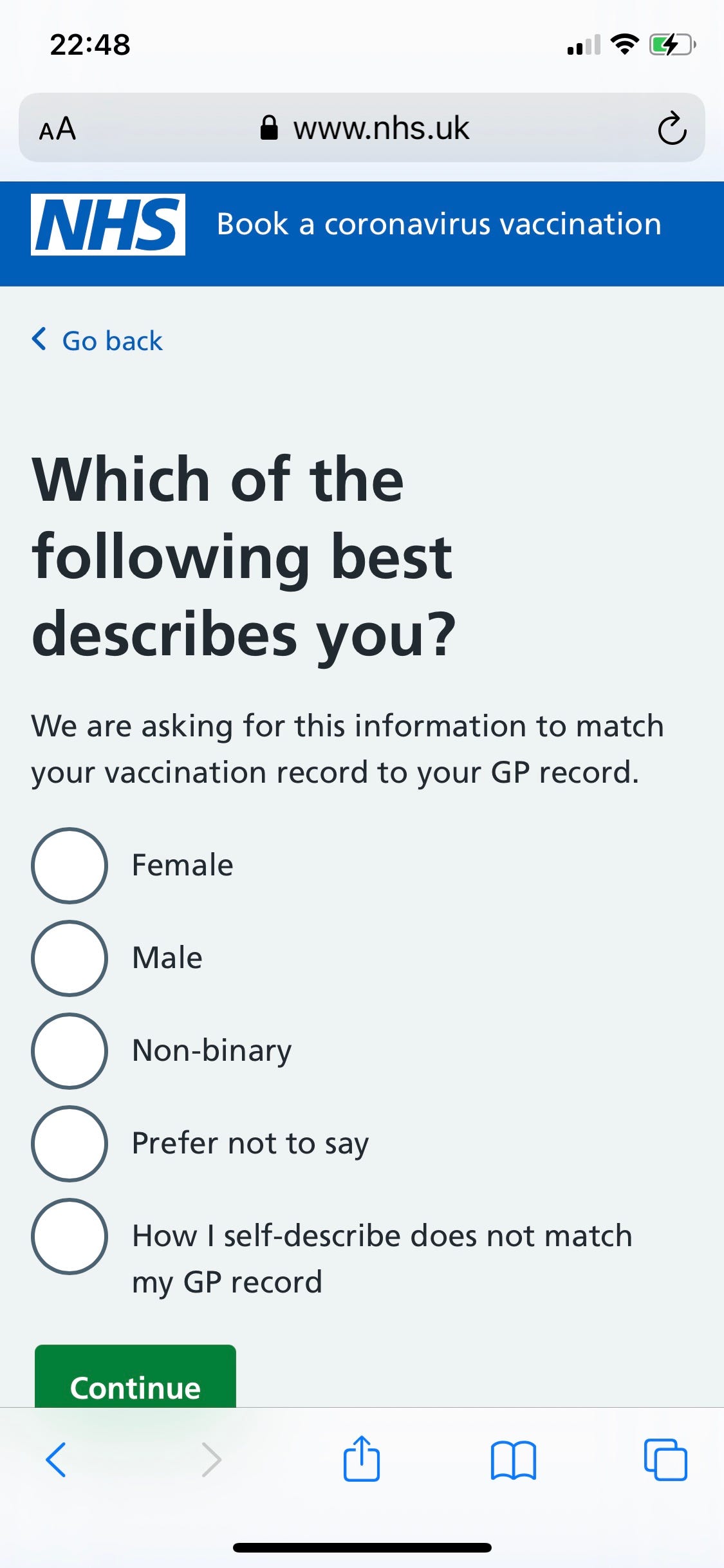

Emma Parnell describes the first workaround solution they came to for solving this, when they launched the vaccine booking system in January.

The team did not want to ask people the binary sex question.

But the trouble was the Application Programming Interface (API) offered by the PDS system for matching patents with their records requires a string that looks something like [name] [date of birth] [gender] [postcode] to check whether a patient exists and link them to their records.

Some other services have avoided the sex/gender question by setting up the API to query four times (that is they don’t ask you your sex or gender on the front-end form but have the back-end software check four times to see whether there is someone with your name and details listed as male, female, unspecified or unknown). But doing this pantomime for everyone was judged to be too much of a performance risk for this high-profile national system.

So instead they set up the booking system with a trick question, “Which of the following best describes you?”, with the options male, female, non-binary, prefer not to say and “How I self-describe does not match my GP record”.

This is a trick question for two reasons:

- It suggests that some people’s medical record lists them as “non-binary“. This is a fictional category. In fact what the system did, as Parnell explains, is “do multiple API calls on the last three options” – that is, if you pick any of the last three options the software would check if there was a patient listed with your details who was male, then then check if there was one who was female, then unspecified or unknown.

- It forces people to declare a gender identity. The way the question is stated fudges whether it is asking about sex or gender. Most people won’t notice and will just answer with their sex, but eagle-eyed gender-critical patients will notice that the options of male, female and non-binary mean you are being asked to declare an internal sense of gender identity, which you may not believe in.

The government shouldn’t be asking people trick questions. And the Data Protection Act requires that it explains what the information for. As Parnell notes:

“There are people across government doing the best they can to plaster over the cracks but when we add the ‘why are we asking this’ reveal, we can’t write ‘because our database only holds two fields’. So what do we write instead?”

Ultimately they fixed the problem this week by removing this front end question altogether and changing the back end API so it no longer has to ask about “gender” at all.

This means no service connecting to PDS for matching purposes needs to ask this question. This was a real win and I’m proud of everyone who contributed.

The implication of this change (which Parnell does not address in the article) is that if “gender” is no longer required by the PDS for matching purposes, and if the data contained in it is unreliable as a functional attribute (indeed it is clinically dangerous) the question arises: what is it for?

Data-protection law says that institutions should keep information on us that is accurate and purposeful. This is not.

Susan Bewley, Margaret McCartney, Catherine Meads, and Amy Rogers writing in the British Medical Journal yesterday warned against the conflation of sex and gender in healthcare:

“Medical care requires an understanding of the difference between sex and gender categories: untangling them is crucial for safe, dignified and effective healthcare of all groups.”

Bewley, McCartney, Meads, and Rogers

We think the NHS must now go back to the drawing board and fix its data systems so that it records sex accurately, for clinical purposes, and keeps it private where it is not needed (including for matching purposes). We will be writing to them to find out what they intend to do.

Losing sight of public purpose

Emma Parnell frames this data challenge with a touching story of personal concern for her transgender dad (who she refers to as they).

Parnell also writes that testing with the trans and non-binary communities was paramount:

“Seeing people see themselves in forms they are so used to being excluded from was all the evidence we needed, not just for the implementation of this screen but to make the case for wider change.”

It’s clear that in 2021 how we ask this question is important, and the inclusion of marginalised groups is paramount. If we don’t include categories that acknowledge and affirm trans people’s existence, we will continue to exclude a proportion of society. A group of people who continue to face discrimination on a daily basis and experience some of the most significant health inequalities.

This approach of prioritising the self-expression of a small group over the overall purpose of collecting data from the whole population echoes the discredited thinking of the ONS on the census sex question.

The idea that official government forms and data systems exist to allow people to express themselves and “be seen” is a fundamental misunderstanding of what they are for. They exist to require the minimum of information from all of us to achieve a particular purpose; as Mr Justice Swift explained to the Office for National Statistics last week.

In fact the solution the NHS Digital Service came to in the end is much better than the messy workaround. It does not “acknowledge and affirm” people’s gender identity, it just avoids asking for information that is not needed.

This is a lesson that can be shared.

Digital Identities

The government is developing a Trust Framework for Digital Identities which will have to deal with these interoperability issues across a myriad of applications. Sex Matters has provided input to explain the pitfalls of conflating sex and gender.

We are developing a public discussion paper to outline the issues and potential solutions.

If you want to know more about this project or support it, contact [email protected].

Breaking the silence

The misreporting of sex in official government data systems is a significant problem for the development of robust and trustworthy digital identity systems. But it is one that is barely talked about.

Caroline Criado Perez wrote a whole book about why sex matters and about data bias, but had been silent until yesterday’s tweet about the corruption of official records and statistics on sex. There is something eerie about one of the country’s most celebrated popular feminists, a champion of data on women, apparently not having noticed the extraordinary crowdfunded challenge to the ONS.

The same eerie silence also envelopes the BBC’s numbers guy, Tim Hartford, the medical anti-bullshit writer Ben Goldacre, the cluster of NGOs who work on promoting sex-disaggregated data, the open government data, and digital identities community and the world of professional feminist organisations.

Their reluctance to talk about it is no doubt motivated by self-preservation and the fear of being punished for speaking up. We cannot allow such fear to rule the people charged with running the systems that keep people safe.

Simon Briscoe, ex-Statistics Editor of the Financial Times and a former treasury statistician, this week spoke up. Writing about the ONS court ruling and the Office for Statistics Regulation, he said:

“In light of the court ruling the OSR must embolden statisticians to say to their colleagues, where necessary, that the data collection processes make no sense! Otherwise, the statistics will fail the OSR’s most basic requirement ‘that statistics serve the public good and meet society’s needs for information’. They will also be out of line with the law.”

Simon Briscoe

We agree. All civil servants, regulators, those who profess to speak truth to power, or act in the public good, must be emboldened to say when things make no sense. Those who seek to make them afraid are not acting in the public interest.

We hope you will share this article with your colleagues.