Census guidance on the sex question ruled unlawful

Census day is 21 March 2021. Yesterday, in a challenge brought by Fair Play For Women, the High Court ordered the Office for National Statistics to correct the guidance they provide online about how to answer the question “What is your sex?”

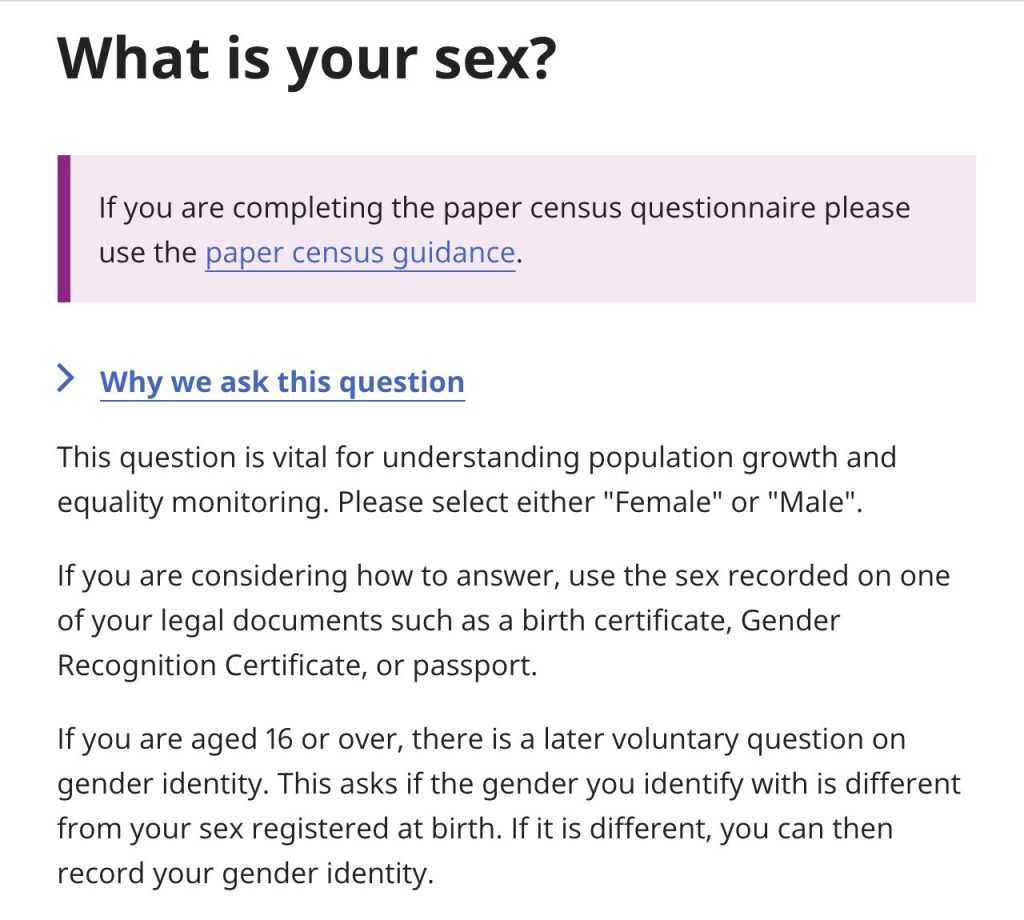

Until yesterday, the guidance for the 2021 census said:

If you are considering how to answer, use the sex recorded on one of your legal documents such as a birth certificate, Gender Recognition Certificate, or passport.”

Most people will have no difficulty answering that question, and won’t need to go looking for online guidance to help them. But for people who identify as trans or non-binary, it’s not quite so straightforward. Should they give their biological sex, or should they answer according to their gender identity? If their gender identity is something other than male or female, how should they deal with the fact that the question only offers those two options?

What did the old guidance mean?

The guidance told people that they could answer the question by reference to “one of your legal documents, such as a birth certificate, Gender Recognition Certificate, or passport.” It takes a GRC to get your sex changed on your birth certificate, but it’s surprisingly easy to change the sex recorded on other official documents: in many cases, you just ask.

With this guidance anyone who had changed the sex written on any official documents would have a completely free choice which sex to give: they could either pick what was written on their birth certificate, or what was written on their passport, or driving licence, or NHS record, or whatever they had changed.

Why did Fair Play For Women say the guidance was unlawful, and did the judge agree?

The Census process is tightly controlled by legislation. ONS is given power to conduct censuses collecting certain kinds of information by the Census Act 1920. The Census (England and Wales) Order 2020 tells it exactly what information it must collect in the 2021 census. Schedule 2 to the order, headed “Particulars to be stated in returns,” sets out what should be asked.

Paragraph 8 is “Date of birth and sex.” The precise form of the questions that must be asked is prescribed Schedule 2 to the Census England (Regulations) 2020. The question that must be asked about sex is “What is your sex?” and the offered answers are “female” and “male.”

FPFW said the guidance was unlawful because the ONS was going to tell people that they could give an answer to the “sex” question that was untrue. Answering the census truthfully is compulsory: giving false answers or (with a few exceptions – the sex question is not one of them) failing to answer is a criminal offence, so in legal terms that was a big deal. The guidance was inviting people to break the law.

FPFW argued that it was obvious that the sex question was asking about biological sex (almost invariably the same as the sex recorded on your birth certificate), apart for people who had a GRC. If you have a GRC, your sex is deemed by law to have changed for all purposes – unless a specific statutory exception applies. There’s no legislation that says a GRC doesn’t change your sex for the purposes of a census, so people with a GRC must give their legally deemed sex, not their biological sex, in answer to the question. But everyone else must give the answer that is literally true.

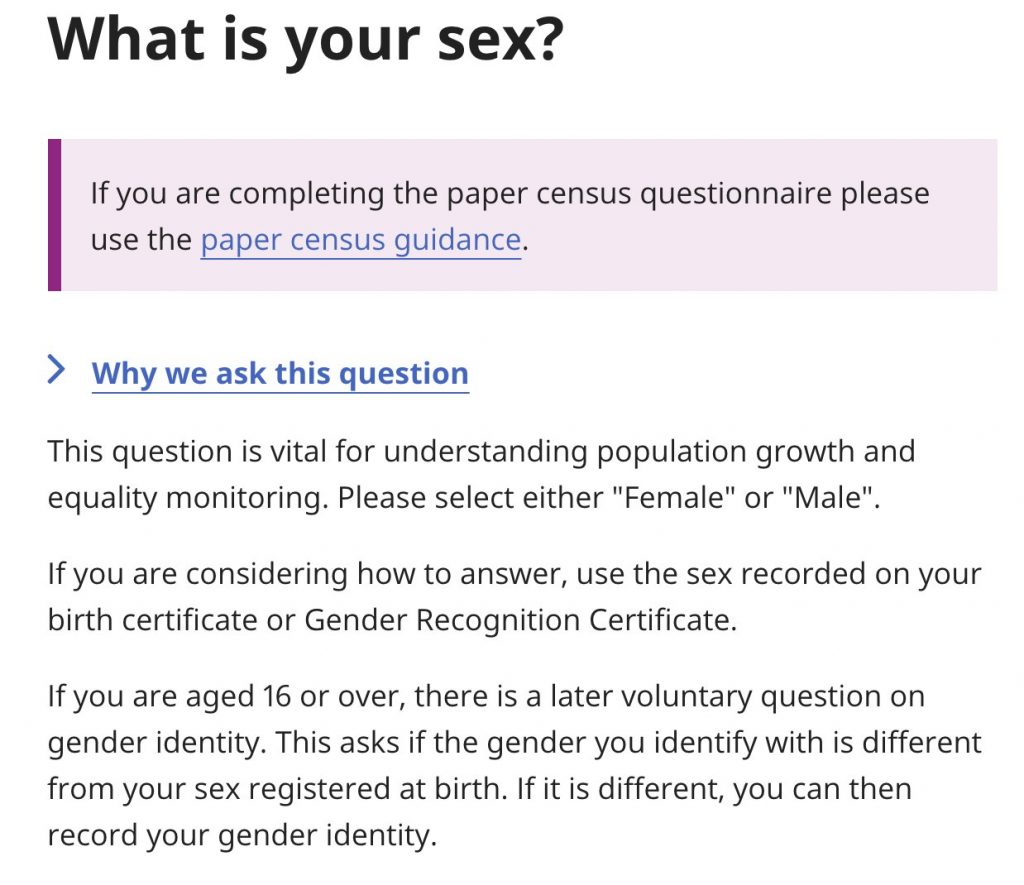

The ONS said that “sex” was an “umbrella term” that could mean self-identified sex, sex recorded on a birth certificate, sex as recognised by law or sex as recognised by any document – and they were entitled to pick whichever meaning they thought best. The judge disagreed. Although this was only a preliminary hearing of FPFW’s application for permission to seek judicial review, he stated his conclusion in unequivocal terms: the ONS guidance was wrong. He ordered the ONS to change the guidance on its website pending a full hearing, and it complied within a couple of hours:

What happens next?

The judge ordered a full hearing of the claim on Thursday 18 March, three days before the Census. Most of the same arguments seem likely to be repeated at slightly greater length, and then a judge will decide finally whether the ONS guidance was lawful or not. That will be the end of the case, unless one side or the other gets permission to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

Why is this important?

As the ONS guidance itself says, “This question is vital for understanding population growth and equality monitoring.” Answers to the question will only provide reliable information for those vital purposes if they are accurate. Sex matters.

It’s unfortunate that there isn’t a specific exclusion of the effect of a GRC for the sex question in the questionnaire: it would be better if the Census collected information about biological sex (and then seperately whether people identify as transgender, whether they have a GRC or not).

But given that records are kept of how many GRCs are issued, the damage to the data involved in letting people answer according to their GRC is known and limited.

So it matters for the data that the Census collects. But it matters much more widely than that. The ONS is the public body entrusted with collecting reliable data; the statistics it publishes command respect, and are used by researchers for all kinds of purposes. Where the ONS leads, other bodies are likely to follow. Many public bodies, regulators and large and small employers have already ceased collecting diversity monitoring information about sex, and are collecting self-identified gender instead. This judgment – assuming it is upheld at the full merits hearing – will make it much harder for them to defend that practice.