DfE guidance must be clear: schools cannot facilitate “social transition”

Reports about the Department for Education’s forthcoming guidance on trans issues for schools are encouraging, going quite some way towards our recommendations.

The Times reports that schools will be told not to allow children to use opposite-sex facilities or play contact sports for the opposite sex, and to tell parents if their child is questioning their gender.

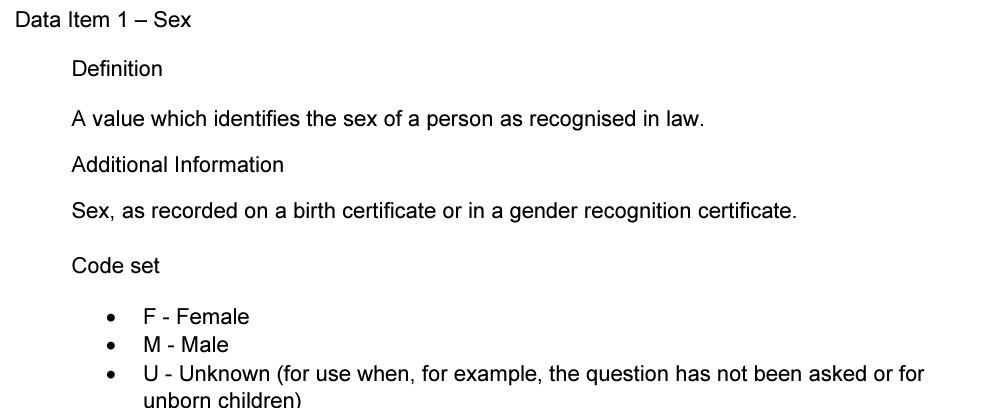

Recent changes to the data standard for recording the sex of children in schools in England and Wales also make clear that schools should record sex (male/female; as registered at birth) for all official purposes.

However, the Times report still seems to suggest that the government may tell schools to allow children to “socially transition”, and interpret gender non-conformity as transition. It states:

“Social transitioning is the process by which children adopt the name, pronouns and expression, such as clothing and haircuts, of their preferred gender identity, which differs from their sex at birth.”

The new data standard unhelpfully suggests that schools may also register “gender identity” (which it defines as “a person’s inner concept of self as male, female, neither or a blend of both” based on self-declaration (boy/girl; man/woman). This sets up an expectation that school rules that distinguish between “girls” and “boys” should be applied based on gender identity, not on sex, and that some boys can become girls and vice versa.

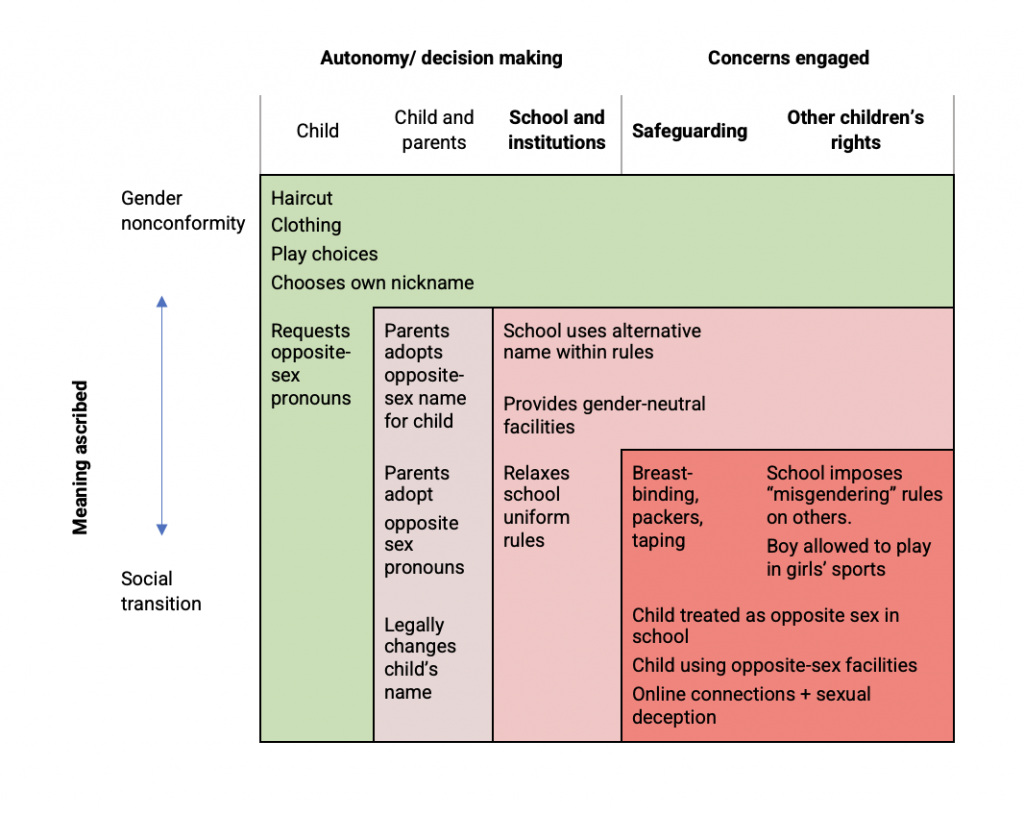

Consider each action individually

We think the DfE’s guidance should avoid embracing the concepts of “gender identity” and “social transition” altogether, and instead consider each question separately based on safeguarding, fairness and the need to operate schools with consistent rules and expectations.

- Should children be allowed to change their “known as” name? In general yes, with parental knowledge.

- Should a child’s sex ever be misrecorded in the school roll or other records? No.

- Should a school ever mislead teachers, pupils and other parents about what sex a child is? No.

- Should a boy ever be referred to as a girl, or a girl ever be referred to as a boy, by teachers and other staff? No

- Should boys be allowed to have long hair and girls to have short hair? Yes.

- Should children be allowed to wear uniform usually associated with the opposite sex? Schools may decide whether or not to have sex-based uniform restrictions.

- Should children be allowed to use opposite-sex facilities? No.

- Should children be allowed to play sports for the opposite sex based on their gender identity? No, and that should include non-contact sports.

- Should a child who is experiencing body dysmorphia or gender dysphoria be provided with alternative facilities? Yes, where possible.

These rules would enable schools to accommodate children with gender issues or who are gender non-conforming without affirming or promoting transition.

For example, a little boy who wants to wear a school dress should not be bullied, but should not be called a girl. A girl in primary school might play football on a team with boys. This doesn’t mean she is a boy. If playing football on a team with boys is allowed at a particular age, this should be an option open to any girl who is good enough, without any need for her to call herself a boy, and no encouragement for her to do so.

If a boy or girl wishes to refer to themself by the opposite-sex term (or non-binary, transmasc, transfemme etc) and to adopt neopronouns among their friendship group or within their family, the school cannot forbid this, but teachers should not adopt this language or make other children adopt it.

Schools should review rules and facilities to reduce sex-based distinctions which are not justified, and consider how children with mental-health issues related to their sex are accommodated (for example by providing a unisex single-user toilet option). But they cannot accommodate the idea of a child “socially transitioning” to be treated as the opposite sex during their school career without weakening safeguarding and violating other children’s rights.

Accommodation not “social transition”

The concept of “social transition” implies that a decision taken at a particular age commits the school to continuing to treat the child differently than before “transition”. This commitment is impossible to keep. Schools must apply clear rules and safeguarding in every year, and cannot consider that a child has moved into a different category.

No rules should be applied differently based on declarations of gender identity. For example, schools should facilitate girls who wish to play football and boys who wish to dance, because these are activities that can be done by either sex. A girl might find herself competing against boys in primary-school athletics based on her speed, but a boy should not be allowed to join the girls’ netball team on the basis of a declared gender identity.

The Times report states:

“While some campaigners believe schools should refrain from affirming or facilitating a child’s social transition until medical advice has been issued, Whitehall insiders say this is out of step with NHS guidance and the Cass review.”

This is the wrong approach. Neither the Cass Review nor NHS guidance has considered the rights of other children in school or the practicalities of “social transition” for schools. Schools must respect the rights of all their pupils, and must not allow one child’s doctors (whether NHS or private) to dictate their policies (see our response to the NHS draft specification).

The forthcoming DfE guidance should make clear what schools can do safely and fairly, and then communicate these limits to NHS decision-makers. Doctors must be told that they cannot expect schools to treat their young patients as anything other than their actual sex. And doctors should then make sure that their patients understand this.

The recent tribunal case of Dr Webberly v GMC confirmed that it is possible to get a diagnosis of gender dysphoria from a private doctor after as little as a three-hour consultation. School guidance should be clear that whether or not a child has such a diagnosis makes no difference to the extent to which children with gender issues can be accommodated.