Our response to the NHS interim service specification consultation

The NHS’s public consultation regarding the interim service specification for youth gender services ends on 4th December. We would encourage people to respond, including parents, teachers, school leaders and clinicians.

We have published our full response.

Sex Matters joins Transgender Trend and the Gay Men’s Network in welcoming the broad direction of the new specification, which responds to the recommendations of Dr Hilary Cass and takes an approach that is based on holistic, exploratory mental-health care, and is mindful that gender incongruence may be a transient phase for children and young people.

However, we are concerned that the service specification recommends “social transition” without defining what that means or considering the impact on other children (particularly in schools).

What is social transition?

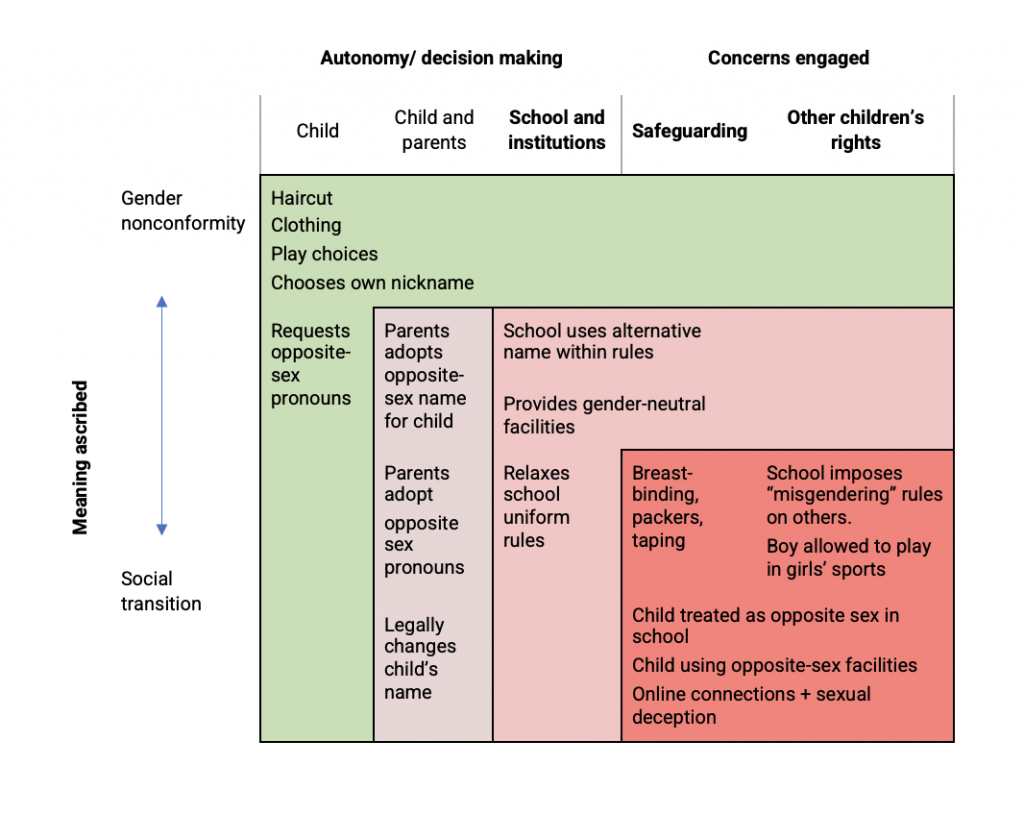

Typically, “social transition” is described as changes to hairstyle, clothing, name and pronouns. But this leaves unsaid the important conceptual and practical expectation of “social accommodation”: that a child’s choice of words about themselves will be enforced on others, and the child will be treated as if they actually are the opposite sex. This may be brought about by misrepresenting a child’s sex to other adults and children and on records, imposing “misgendering” rules and granting the child permission to use opposite-sex facilities and play in opposite-sex sports. Other potential elements of social transition include breast-binding and genital prosthetics to make a child’s body look more like the opposite sex.

Mapping risks and concerns

Organisations such as WPATH, Mermaids, Stonewall and Gendered Intelligence have responded to the consultation stating that social transition is a matter for personal autonomy for children and families. But at the same time they have been pressuring schools to make extreme social accommodations including treating children as the opposite sex.

A child experiencing gender-identity issues is not a child of the opposite sex. Institutions that treat a child as if they have changed sex are ignoring the safeguarding risks this poses for that child.

The NHS should not make policy on social transition without first defining it. We suggest that it breaks down each potential aspect of social transition and considers it in terms of safeguarding concerns and other children’s rights.

Impacts on other children

If a child undertakes a social transition while at school, this impacts on other children, who may be lied to, confused, misled or told keep secrets about the sex of one of their peers. Social transition may also override their boundaries by assuming they consent to sharing single-sex toilets, changing rooms, showers and sleeping accommodation with a member of the opposite sex. The impact on their development, their ability to trust their own senses and judgement, their acquisition of a coherent, developmentally appropriate understanding of the two sexes, and their ability to develop and maintain personal boundaries and an understanding of consent have not been considered. Fairness and safety in sport are also concerns.

Schools and education regulators should be properly consulted

Organisations that will be asked to accommodate changes to the social and institutional environment for children need clarity on what is proposed in order to be able to respond effectively to this consultation. In the absence of such clarity, it will be impossible to gather a meaningful response in some important areas, in particular from from headteachers’ associations and education regulators.

The experience of the previous GIDS service is that areas of ambiguity and split responsibility between different institutions become the locus for intense pressure on professionals and parents. Arguments are used by campaigning groups which support extreme approaches to paediatric transition, and sometimes by children and parents, that capitalise on exaggerated fears of self-harm and suicide, misunderstanding of equality law and fear of being labelled “transphobic”. Unless these ambiguities are resolved, and lines of responsibility are made completely clear, the shift in approach recommended by Dr Cass will be harder to implement.

Recommendations

We encourage NHS England to commission a full review of the implications of proposed approaches to social accommodation, either as part of the Cass Review or separately. This should consider schools’ duty of care towards all children with regard to safeguarding, consent and human rights.

We recommend that in the service specification it takes a “do no harm” approach and tackles unsafe practices by schools and other institutions in the same way it has decided to tackle prescribing from unregulated sources and unregulated providers. Children and their families should be strongly discouraged from pressuring schools and other organisations to treat any child as if they are a member of the opposite sex. It is not a reasonable or safe expectation. This should be made clear in the “psycho-educational materials” proposed in the specification, and in individual and general guidance to schools.

In cases where such steps have already been taken (such as where a child is in “stealth” to their peers) the Service should advise the school and other organisations involved to assess whether local safeguarding protocols and duty of care have been breached.

Clarity about the Equality Act needed

The Equality and Health Inequalities Impact Assessment released with the draft specification does not consider how this policy impacts on other children through recommendations to schools. This is very concerning. Clinicians cannot be allowed to make recommendations that force other children to act as non-consenting participants in delivering a course of treatment to a peer as a condition of receiving their own education.

The EIA also misinterprets the protected characteristic of “gender reassignment”, departing from the Equality Act 2010 by suggesting that it requires diagnosis. This misunderstanding makes the service specfication’s intention of limiting social transition to those under clinical supervision vulnerable to continual renegotiation and potentially legal challenge.

NHS England, the Department of Education, Ofsted and the Equality and Human Rights Commission should have a shared concept of what are reasonable requests for the social accommodation of children with gender distress, and what are not, based on a common understanding of safeguarding and the Equality Act.