Data matters

The easiest way to ask about sex is to ask a simple question and expect a straightforward answer.

Sex Matters is publishing our own guidance on data collection about sex and transgender identity.

This guidance is intended to provide clear, workable advice, in line with current laws, to anyone who needs to collect data on sex in the public, private or voluntary sector.

Don’t confuse categories!

The question of how to collect data on sex has become fraught. In recent years many organisations have become confused and fearful about recording information on sex (as the Sex not Gender project documents). Many instead ask for “gender” (or gender identity) and some offer a bewildering array of options:

- the NHS Mental Health dataset records people as “Male (including trans man)”, “Female (including trans woman)”, “Non-binary” or “Other”. It does not record their sex at all

- the Information Commissioner’s Office offered job applicants a dropdown menu that included “Male”, “Female, “Transgender”, “Agender”, “Aporogender” “Bigender”, “Demiboy”and seven other options (it has now corrected this)

- Oxfam asks staff if they are “man-identified”, “woman-identified” or “non-binary/gender queer”.

Record data on sex

The easiest way to ask about sex is to ask a simple question and expect a straightforward answer.

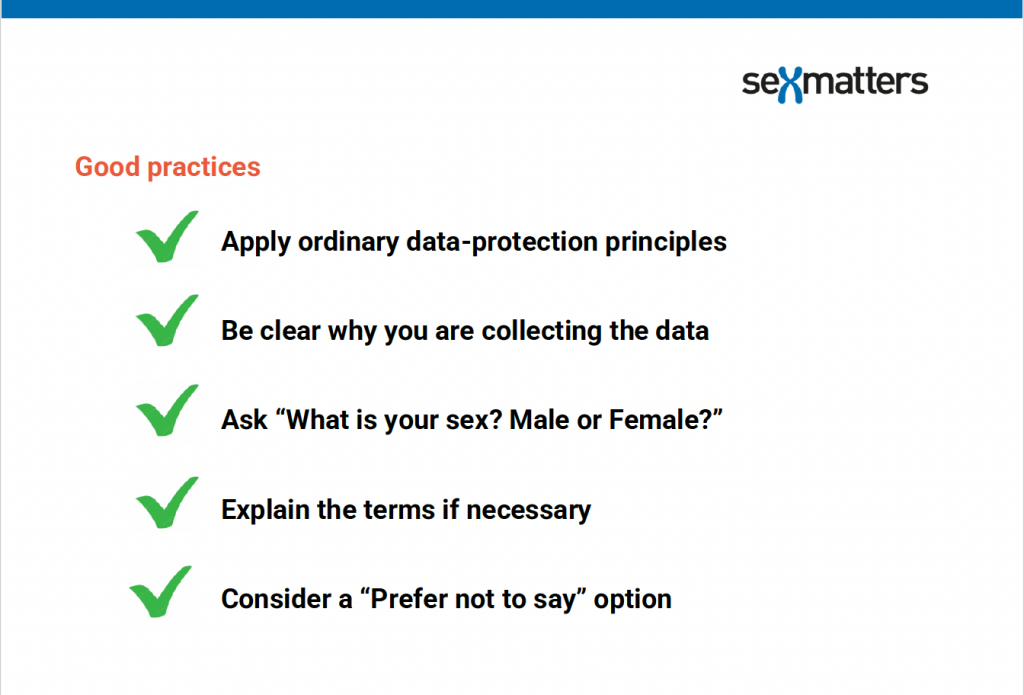

In some cases you may need to provide an explanation of what you mean by sex (“sex as recorded at birth”, or “sex recorded on a current birth certificate or gender-recognition certificate” depending on what the data is for), and in some cases you may want to offer a “prefer not to say” option.

When designing a question, the place to start is to ask what the information is for. Organisations need to record information about people’s sex for many reasons, including:

- because it is required by law – for example, schools must record pupils’ sex

- for healthcare and medical records –for correct diagnosis, screening, analysis of test results, treatments, dosages and so on

- for operational reasons – for example, where a person’s sex is relevant to their job (such as a bra fitter or women’s refuge worker) or where there are sex-based rules about who can access a particular service

- for processing salaries, tax and pensions

- for sports – to decide on eligibility for competitions and to assess and record athletic performance

- for safeguarding – where an organisation places staff in positions of care towards children and vulnerable people

- for social statistics – for example, recording and analysing economic data by sex

- for equality monitoring – for example, to avoid sex discrimination in recruitment processes or to monitor workforces in order to spot patterns of discrimination

- in order to prevent, investigate or prosecute crime.

In almost every situation, if you want to know a person’s sex, what you want to know about is their actual sex (apart from for tax and pension records, which are linked to sex as modified by a gender-recognition certificate).

Data on sex is not sensitive. It is collected and recorded routinely.

Do you want to record data on whether people are transgender?

You may want to also collect data on whether people identify as transgender. This is sensitive data. You should ask about this only if you have a good reason and have considered the privacy implications of collecting the data. It should not be collected routinely. Some potential reasons for asking people about transgender identity are:

- operational – to identify transgender people as a population with specific needs

- for social statistics – because you want to know how many people identify as trans in a particular population

- for equality monitoring – “gender reassignment” is a protected characteristic and you may choose to monitor it (although you should consider whether this is possible in practice).

“Appearing inclusive” or “Wanting respondents to feel seen” are not good enough reasons to collect this data. Data-protection principles require that there is a lawful basis for collection, and that the information is used only for purposes that have been identified in advance.

If you want to know whether people have a transgender identity, you should ask this separately from the sex question. Responding should be voluntary.

Should you include a transgender question in equality monitoring?

“Gender reassignment” is a protected characteristic in the Equality Act. However, this does not mean that you must collect information on this characteristic. The small number of transgender individuals in the population means that the data collected is likely to be unusable.

If you do decide to collect such information, we recommend that you treat it as special-category data (like sexual orientation and religion). You should provide your data subjects with sufficient information to understand how you are processing their special-category data and how long you will retain it for.

There is no standard way to ask people if they identify as transgender, and the recent census for England and Wales demonstrates a central difficulty. If the question is confusing, the number of people who unintentionally indicate that they are transgender may overwhelm the data from the small number of people who genuinely identify as transgender. Your survey design should seek to avoid this.

A simpler question may be better.

Some organisations have developed questions that directly relate to the definition of the protected characteristic of “gender reassignment” in the Equality Act. These are intended for the purposes of equality monitoring. But they are legalistic, difficult to understand and not widely used.

Privacy and the Gender Recognition Act

Around 5,000 people in the UK have a gender-recognition certificate (GRC). This creates difficulties for organisations as there are strict conditions around disclosing information on a person’s actual sex if you have acquired the information that they have a GRC in an official capacity.

Our document sets out the different ways that organisations have tried to deal with this, including policies that involve putting people’s records into two layers of manilla envelopes inside locked filing cabinets.

One way to avoid running into problems with GRCs when collecting and using sex data (if your situation is not covered by a specific exception in the Gender Recognition Act) is to make sure that you are explicit that you collect information on actual (“biological”) sex, explain on the form why you are collecting the data and obtain consent for its disclosure as part for the range of purposes for which it is needed.

Take action

- Join us for a webinar to launch the guide.

- If your organisation collects data on sex, download and share our guide with the relevant decision-makers.

- If you are concerned that an organisation is misusing your data by confusing sex and gender, use our template letter to make a complaint and follow the guidance from the Information Commissioner’s Office to follow it up.