The ONS should admit its gender-identity question failed

The Office for National Statistics has released the final summary of its investigations into the quality of the England and Wales census data from the “gender identity” question.

A clear assessment of the quality of the data is important, both because the data will be used to drive understanding, decisions and resources, and because the form of questions used in the census is replicated by other organisations.

The ONS has refused to face up to the predictable consequences of taking advice from activist groups which have little interest in the integrity and credibility of census data. It has not admitted that what it produced falls short of the standards of accuracy needed for national statistics.

Answering the gender-identity question

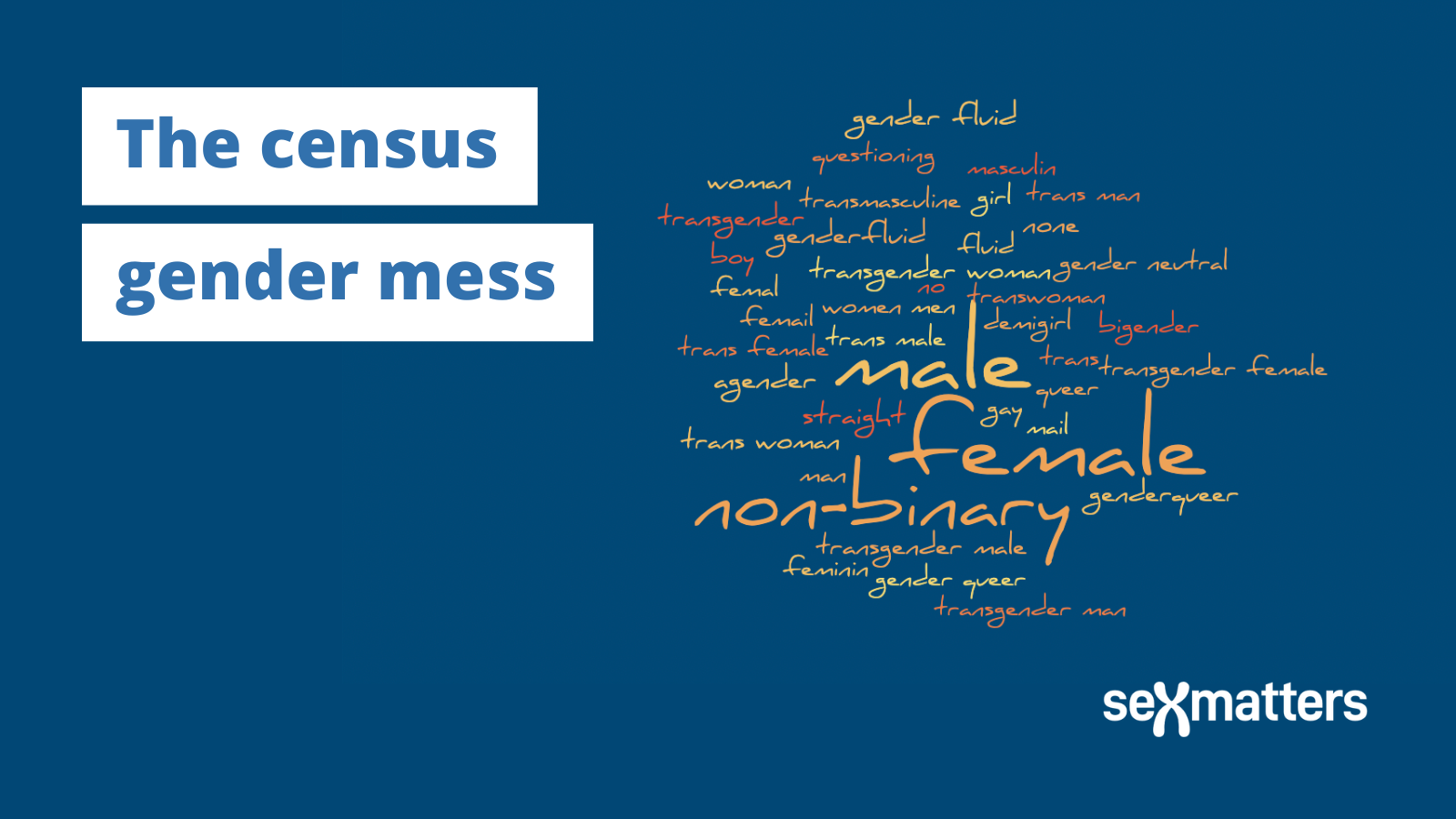

The newly released data reveals widespread confusion about what the gender-identity question was asking.

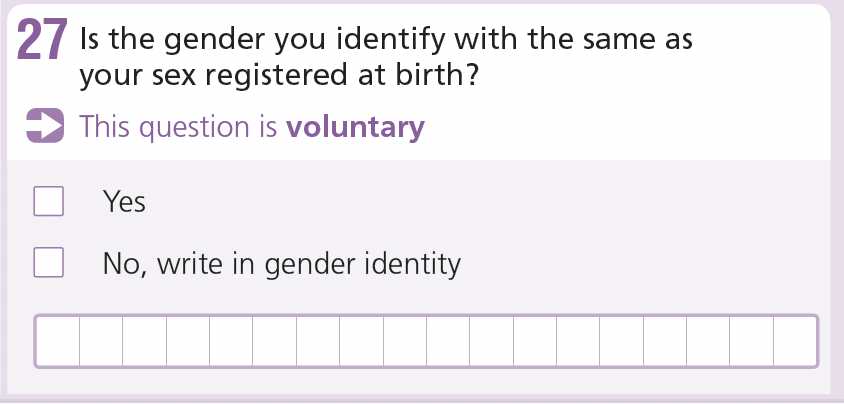

The census included a voluntary question which sought to distinguish people who identify as transgender and then offered them an open question.

The headline result released by the ONS at the beginning of the year was that 262,000 people (0.5% of the population aged 16 and over) were transgender. The ONS said at the time it released the original data: “These new figures will be vital in helping shape services in years to come.”

However as Professor Michael Biggs (a member of Sex Matters’ board) has pointed out, the distribution of this population suggests potentially widespread misunderstanding of the question, particularly by those who do not speak English well.

The ONS said that it counted 48,000 “trans men” and 48,000 “trans women” in England and Wales.

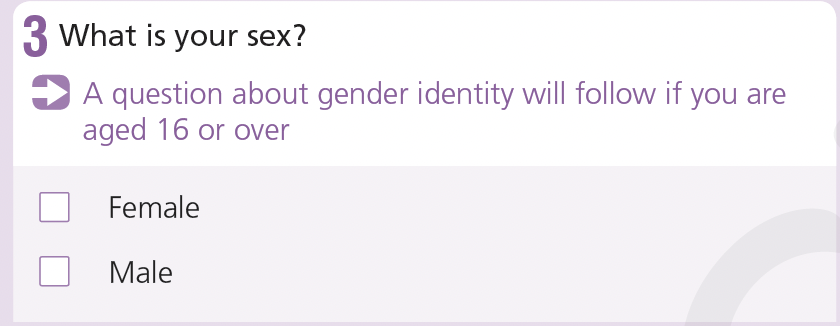

But 68% of those classified as “trans men” answered “male” to the sex question, and 66% of those classified as “trans women” answered “female”.

Given that fewer than 6,000 people have gender-recognition certificates (GRCs) that would legally permit them to answer the sex question as the opposite to their actual sex, most of those classified as “trans men” or “trans women” either lied about their sex or are not trans: they answered the sex question correctly and were confused by the gender-identity question.

The data released today gives some further clues to what happened. It shows that most of those the ONS classed as “trans men” were people who wrote some variation of “male” in the gender-identity box (and would also have ticked “male” as their sex), and most of the “trans women” were people who wrote in “female”. Given that many of these people wrote matching answers in the sex box perhaps they were not seeking to declare themselves transgender at all.

There were a bewildering array of answers in the freetext box. Some described themselves as “straight” or “gay” in English and some other language, such as Romanian. The ONS classified “gay” as being another gender identity but “straight” as being someone with a gender identity matching their sex. “I don’t have a gender identity” was counted as gender the same as sex at birth but “none” was counted as an other gender.Some wrote in the words for “male” and “female” in foreign languages, including Polish, Spanish and Italian, and were counted as transgender.

Only 3,335 of those the ONS say are “trans men” used terms that made clear they understood the question and identified as transgender, such as “transgender male”, “transgender man” or “female-to-male”. Similarly, only 2,825 of those the ONS say are “trans women” described themselves as “transgender woman”, “trans woman”, “male-to-female” or similar. Most simply said “male” or “female”.

The ONS says: “given other sources of uncertainty, not least the impact of question non-response, we cannot say with certainty whether the census estimates are more likely to be an overestimate or an underestimate of the total number of trans people aged over 16 years in England and Wales.”

This is a poor excuse for a response from the nation’s official statistics body, which spent £1 billion conducting the census. It now needs to admit that it cannot say with any confidence what the vast majority of people who answered the gender-identity question meant by their answer.

One illustration of the degree of uncertainty can be seen by comparing two subgroups of the people the ONS classed as “trans women” or “trans men”: those who gave answers which clearly indicated that they have a trans identity, and those who do not speak English very well. The latter group is around two and a half times as big (we do not know how much they overlap).

| Classed as: | “Trans woman” | “Trans man” |

| Wrote in something specific like “transgender woman” “trans woman”, “trans man” | 2,825 | 3,335 |

| Speaks English less than “very well” | 8,135 | 8,580 |

In response to the observation of a high rate of transgender identification among people born abroad or not speaking English fluently, the ONS said:

“These patterns might be thought consistent with some respondents not interpreting the question as we had intended but could also be affected by other considerations such as cultural factors. For example, it is possible (but difficult to confirm) that trans migrants might have specifically chosen the UK because of its civil rights legislation and greater social acceptance than many other countries, impacting the trans proportion among that population group.”

This is both laughable and desperate.

The ONS also admitted today that the follow-up Census Quality Survey (in which a small sample of the population is telephoned to double-check their answers) found much lower agreement rates for people who had initially appeared to answer that they were trans on the census than for those who didn’t. The ONS suggests that people may have changed their answer because of the “risk of others in a household overhearing” their response.

The idea that someone could be meaningfully living as if they were the opposite sex without those they live with knowing this is equally ridiculous.

What should happen next?

This is unarguably poor question design, and the ONS should admit this before other organisations use the same question or put any faith in the census data.

The lesson that should be learned is that if you want to know how many people identify as “trans women”, “trans men” or “non-binary”, then offer those as clear options to tick. Don’t ask a confusing question about whether “the gender you identify with is the same as your sex registered at birth” because it will result in a large number of false positives.

You should also ask the sex question clearly and explain that it means biological sex, which is observed and usually recorded at birth. Sex Matters has published guidance on how to ask questions about sex that will yield reliable results.

The gender-identity question that the ONS designed was clearly a failure which did not yield reliable information. It should be officially retired, with an apology and an explanation to discourage others from using the same question. A warning should be put on the data and it should not be designated as national statistics. If the ONS will not do this unprompted, the Office for Statistics Regulation should insist on it.

The ONS should also release analysis of the data breaking down the write-in answers by sex, and by the number of households with multiple trans people in a family (which may also suggest the questions were misunderstood).