“Misgendering” and the Scottish Hate Crime Act

On 1st April, the Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act came into force. The law has generated headlines across the world, mainly due to concerns about its potential impact on freedom of speech; in particular, gender-critical speech.

One of the most controversial aspects is the extension of so-called “stirring up” provisions to characteristics other than race, including transgender identities (which expressly covers non-binary identities and cross-dressers). The threshold for what counts as hateful is set low – at a single act of speech that is merely “abusive” and not threatening or violent.

After years in which transactivist lobby groups have trained police forces and judges to embrace gender ideology, and to view “misgendering” as offensive, women’s-rights groups have feared that simply mentioning the biological sex of trans individuals could result in investigation and even prosecution.

Police not investigating

JK Rowling marked the new law by tweeting that certain high-profile “transwomen” are in fact men, daring Police Scotland to charge her.

The force has confirmed that there were complaints, but it will not take them further and they will not be recorded as a non-crime hate incident. First Minister Humza Yousaf said Rowling’s posts on X were a “perfect example” of the distinction between stirring up hatred and people “being offended or upset or insulted”. He added: “Anybody who read the act will not have been surprised at all that there’s no arrests made.” Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said: “People should not be criminalised for stating simple facts on biology.”

Stonewall shifts position

Stonewall also responded, publishing a statement that presents “misgendering” as akin to criticising religion.

“The PM, and high-profile commentators, are incorrect when they suggest that misgendering or ‘stating facts on biology’ would be criminalised. This is no more true than stating that the existing law has criminalised the criticism of religion. This kind of misrepresentation about the Act and its purpose only serves to trivialise the violence committed against us in the name of hate.”

This is a big shift in position.

In Stonewall’s hate-crime resource, it defines being “insulted, pestered, intimidated or harassed” as a hate crime. In its Transphobic Hate Crime Report in 2020, Galop UK, a partner organisation of Stonewall, stated that the top three hate crimes against trans people were “invasive questioning”, “deadnaming” and “verbal abuse” (vaguely defined).

As Sex Matters wrote in February, even before the Scottish hate-crime law, women and men were being investigated, questioned and arrested for gender-critical speech. Stonewall has never previously stated that “misgendering” is not abuse, or that gender-critical people’s freedom of expression should be protected. In fact, it has said quite the contrary.

In 2021, when the Equality and Human Rights Commission intervened in the Forstater case to support the rights of gender-critical people at work, Stonewall signed an open letter that described the intervention as “a kick in the teeth”. It accused the human-rights watchdog of putting its “organisational weight behind a movement that has only contributed to rising hate for trans people in communities, creating a policy environment where it is harder for trans people to access their rights”.

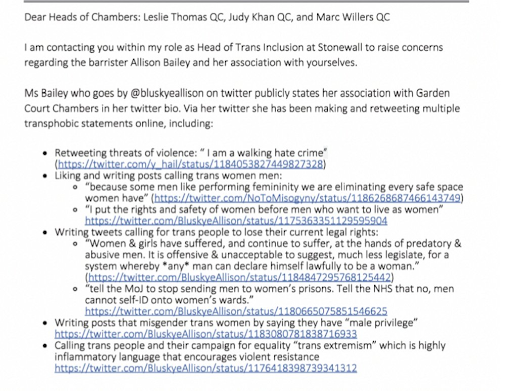

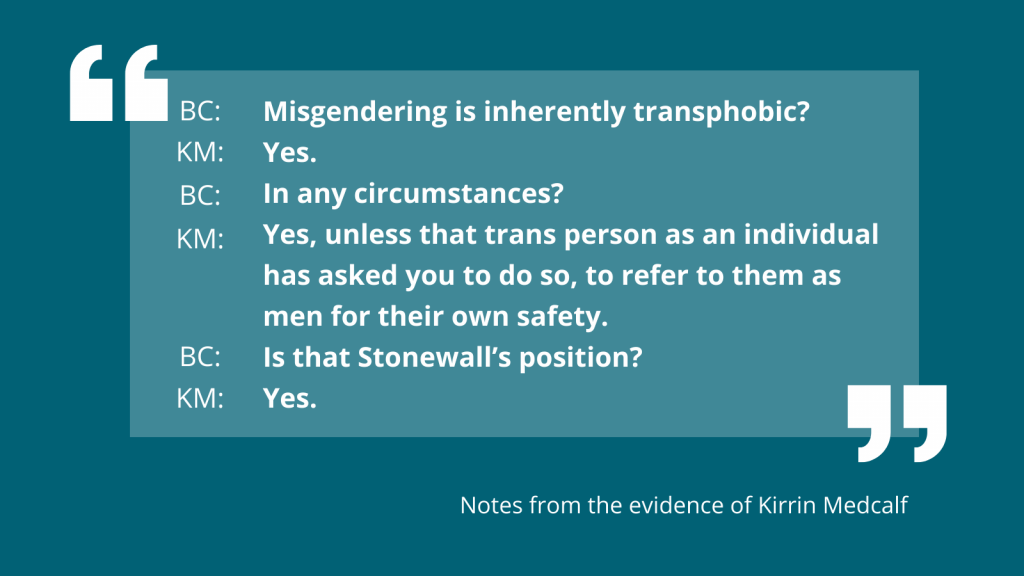

In May 2022, the employment-tribunal hearing of barrister Allison Bailey revealed that Stonewall staff had reported her to her chambers, Garden Court, for “misgendering”. During cross-examination, Stonewall’s head of trans inclusion, Kirrin Medcalf, confirmed that Stonewall’s position was that “misgendering” is “inherently transphobic”.

Stonewall has criticised the EHRC’s chair, Baroness Kishwer Falkner, for using the term “trans-identifying people” and for meeting with gender-critical groups.

In its response to the Department for Education’s consultation on gender-questioning children, Stonewall stated that referring to a child accurately by their sex in school could constitute unlawful discrimination:

“Not using a trans pupil’s chosen pronouns (no matter their age) could be considered discrimination or harassment under the Equality Act 2010 as noted in the example on page 65 of the EHRC’s Technical Guidance for Schools in England.”

The need for clear guidance

The Scottish government itself has been unclear about what kind of speech might be regarded as criminal under the new law. In an interview on Newsnight on 20th March, Fulton MacGregor MSP, when asked whether “misgendering” might become a criminal offence, said that this “depends on the circumstances”. When asked if a complaint about a tweet by JK Rowling that stated that “transwomen are men” would be taken forward by the police, MacGregor could not rule out the possibility, but said he had “faith” that the law would be implemented properly. When questioned by Justin Webb on the Today programme, the Scottish Minister for Victims and Community Safety, Siobhian Brown, could not unequivocally say that “misgendering” wasn’t a crime, instead saying that this was a matter for the police to decide.

The new act states that a person commits an offence if they communicate material, or behave in a manner, “that a reasonable person would consider to be threatening or abusive”. Defenders of the law cite the “reasonable person” as a safeguard for free speech. It is worth considering, then, whether an employee of Stonewall would be considered a “reasonable person”. Stonewall continues to be considered an authority by many on issues relating to sex and gender – including, until recently at least, both Police Scotland and the Scottish government.

In a recent interview with the BBC’s Woman’s Hour, Susan Smith, one of the directors of grassroots campaign group For Women Scotland, pointed out that a minister in the Scottish government would presumably also pass the “reasonable person” test. Within political parties as elsewhere, there is much disagreement over what constitutes “transphobia”, and whether gender-critical speech is a matter of disciplinary action. In 2022, Scottish Green Party MSP Patrick Harvie accused “high-profile people within the SNP” of being “allowed” to “get away with promoting transphobia,” and spoke of reforming internal disciplinary processes.

Last year, Nicola Sturgeon, then First Minister, accused some of those opposed to the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill of using women’s rights as a “cloak of acceptability” for “transphobia”. Joanna Cherry KC MP has been a vocal opponent of gender-recognition reform, and has experienced threats and intimidation. She has said that she received “no support whatsoever from the [SNP] leadership”.

During the process of drafting the new law, several MSPs put forward amendments intended to protect freedom of expression. These were dismissed. As documented by policy analysts MurrayBlackburnMackenzie (MBM), the amendments were described by Harvie as hostile and as legitimising attacks on trans rights.

Another Scottish Green Party MSP, John Finnie, approvingly cited a briefing by the Equality Network, a Scottish charity. This briefing responded to one of the dismissed amendments – which listed several straightforward gender-critical statements as examples of what would not be caught by the new law, such as that sex is a physical binary characteristic that cannot be changed – characterising it as undermining the Act’s purpose: “To add into legislation a list of ‘approved’ statements that include attacks on the fundamental rights of one group of people is entirely wrong.”

Despite promising that it would do so, the Scottish government failed to meet with MBM to discuss concerns regarding the law’s impact on gender-critical people, apparently because it did not want to “upset the transgender lobby”.

Political parties are unclear as to how to respond to accusations of “transphobia” in their own ranks. Yet they expect Police Scotland to be able to respond to such complaints without clear guidance, following a law drafted without engaging concerned stakeholders which lacks safeguards and explanatory notes on freedom of expression. It’s unsurprising, then, that many lack faith that the law will be fairly and properly enforced.

When considering “stirring up” offences, the Law Society of England and Wales concluded that any extension to cover gender identity without an explicit freedom-of-expression clause would lead to a “very real risk of the law being misapplied”. The Law Society suggested an “avoidance of doubt” provision covering “the view that sex is binary and immutable, and the use of language which expresses this”. However, it went on to say:

“There may be circumstances where the manner in which gender critical views were expressed, and the intention of the speaker, meant that the line was crossed into stirring up transphobic hatred.”

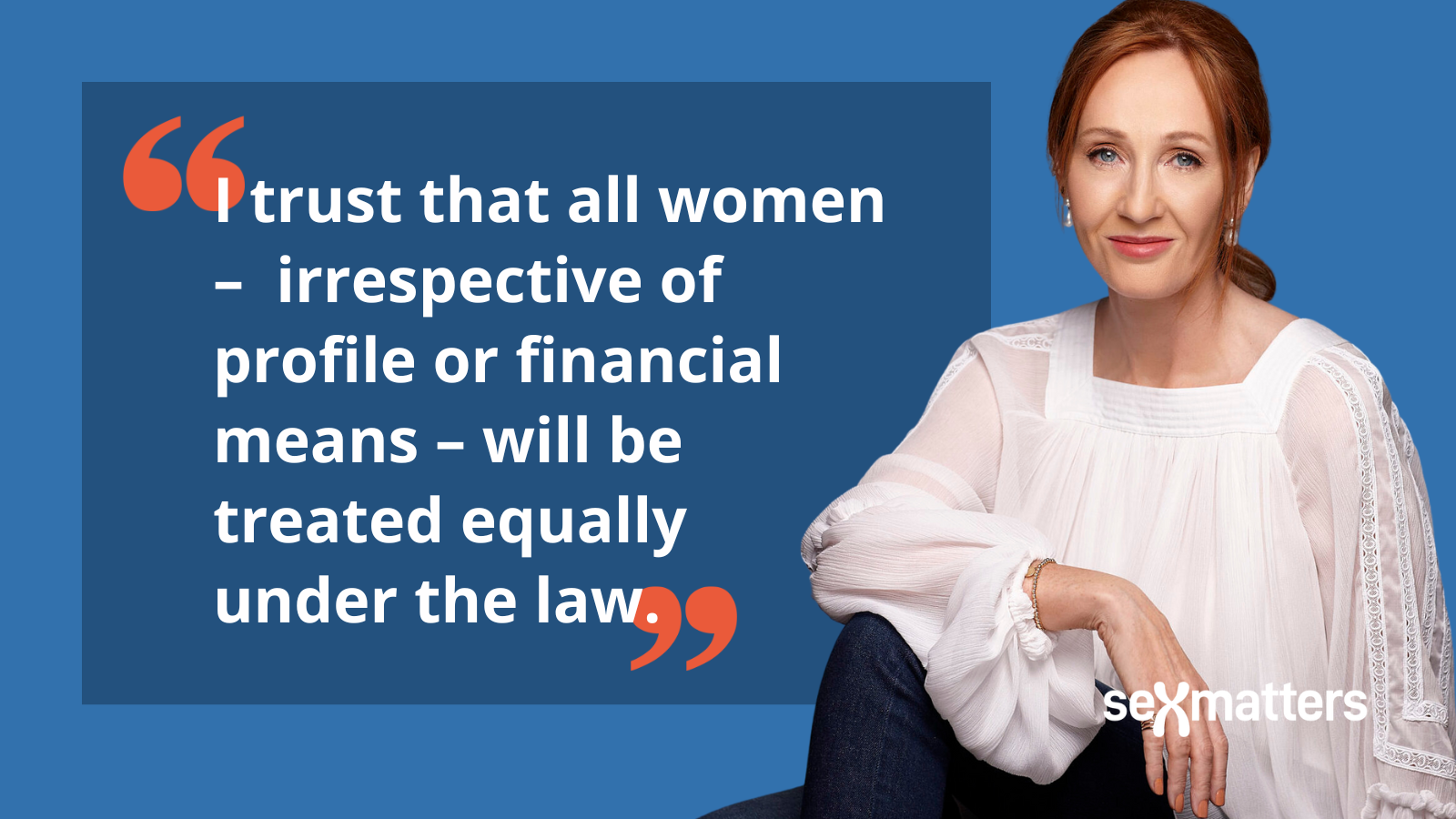

JK Rowling’s tweets have illustrated not only that expressing the general view that transwomen are men is not stirring up hatred, but also that naming individual “transwomen” as men is not either. Rowling tweeted:

“I hope every woman in Scotland who wishes to speak up for the reality and importance of biological sex will be reassured by this announcement [that Police Scotland would not be investigating her], and I trust that all women – irrespective of profile or financial means – will be treated equally under the law.”

Fears not unfounded

Women’s fears concerning the new law’s implementation have not come from nowhere. In a briefing submitted to MSPs as the bill was going through the Scottish parliament, MBM provided evidence of women across the UK having already lost jobs, faced disciplinary action, been interviewed by the police or had details recorded on police databases simply for asserting that biological sex matters.

In May last year, the Free Speech Union (FSU), a non-partisan, mass-membership, public-interest body with more than 10,000 members, stated in written evidence to the UK parliament that 44% of all closed FSU cases since 2020 had concerned infringements of workers’ freedom of expression. Of these, 52% related to the expression of a belief, mainly concerning sex and gender or religion. In the past fortnight, almost 1,000 people have joined the FSU, most of them women.

Last year, Sex Matters wrote to Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, asking him to take urgent action to halt an escalating campaign of violence and intimidation against women in the name of “trans rights”. We explained that women are being threatened with social ostracism, loss of livelihood and physical violence; being shouted down and intimidated at public events; and even being subjected to physical violence – all for insisting on freedom of belief and freedom of expression, and calling for existing sex-based legal protections to be upheld. We have gathered examples of the intimidation, threats and violence that women face from transactivists whenever they try to meet and speak about the law and their rights.

Chilling effect

Police Scotland has said that the complaints against JK Rowling will not be taken further. Even so, activists may still seek to weaponise the new law to silence ordinary women without her fame or wealth. There will still be a chilling effect unless police officers are issued with clear guidance saying that it’s not hateful to state people’s sex, even if they don’t want you to.