Sex and the law at the end of 2023

This blogpost is based on a briefing sent to the Women and Equalities Committee in advance of its session with the Women and Equalities Minister, Kemi Badenoch.

Lady Haldane changes everything

On 1st November the Court of Session upheld the judgment by Lady Haldane from last December that a gender-recognition certificate (GRC) changes a person’s sex for the purposes of the Equality Act. This is a Scottish judgment, but is likely to be persuasive more broadly. Lady Haldane was put on the spot to decide between two possible definitions of the protected characteristic of sex, for one narrow application of the Equality Act. In pronouncing judgment she created consequences that rippled across the operation of the Equality Act.

This judgment means that:

- the natural categories of “male” and “female” are not recognised by the Equality Act 2010

- the law treats transgender people with and without a GRC differently, even though they are not different in any material respect.

On 8th December Lady Haldane upheld the lawfulness of the UK government’s use of Section 35 to block the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill. The reasons were based on this same interpretation of the Equality Act.

The government argued that the way the Equality Act 2010 and the Gender Recognition Act 2004 interact poses risks to women’s rights and safeguarding, which would be made worse with self-ID.

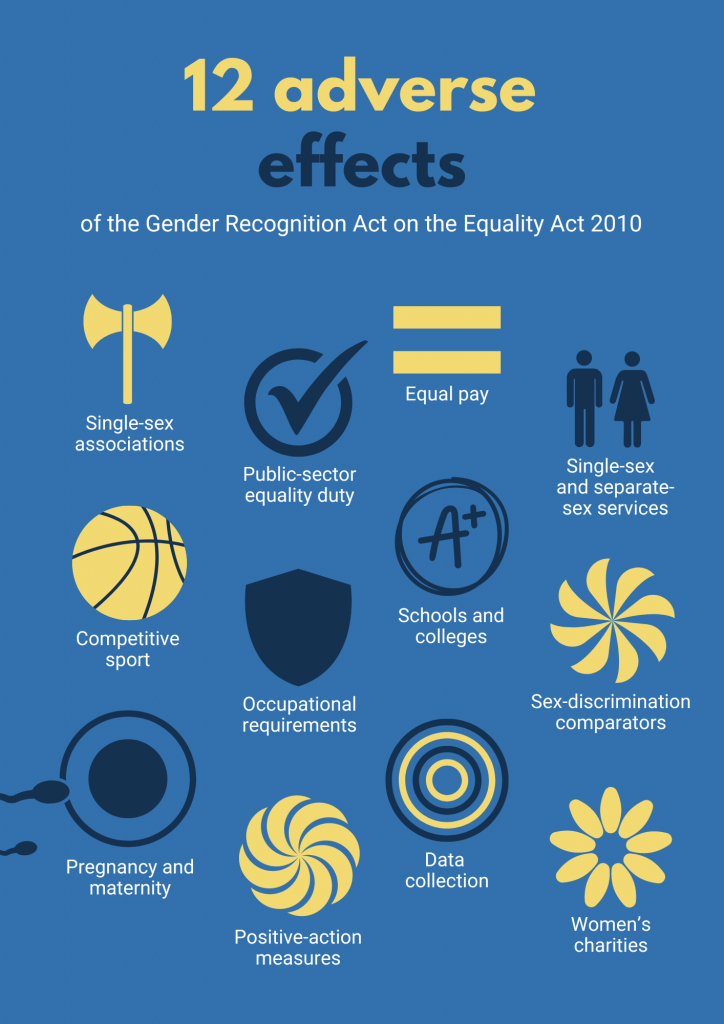

The 12 adverse effects

The government highlighted eight adverse effects of the action of the GRA for the Equality Act in its justification for the Section 35 Order:

- Clubs and associations. Women’s associations, including associations of lesbians and for sport, are not allowed to exclude men who identify as women from membership if those men have a GRC.

- The public-sector equality duty (PSED). The legal definition of man and woman makes a difference to the groups whose needs and disadvantages a public body is required to consider and advance.

- Equal pay. A single employee with a GRC in a workplace could lead to an equal-pay issue being falsely identified, or to a failure to identify such an issue.

- Single-sex and separate-sex services. Service-providers are finding it difficult to operate, even though it is lawful to provide services that are single-sex, including if this disadvantages trans people. This leads to chilling effects: disincentivising providers from offering single-sex services and leading to women self-excluding because they are told that they may encounter males (and be called transphobic if they object).

- Competitive sports. The legal effect of a GRC makes it more complex to exclude male people from female sports.

- Occupational requirements. There are legal and operational risks when trying to advertise roles that are female-only, if a person with a GRC applies.

- Schools and colleges. Single-sex schools would have problems maintaining clear admission rules if under-18s were able to get GRCs.

- Sex discrimination. A GRC changes the comparators in a sex-discrimination claim, even though in practice there is no material difference between trans people with and without certificates.

The judgment confirmed that all of these concerns were reasonable.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission, in a letter from Kishwer Falkner to the Minister last April, also identified three further issues:

- “Transmen” with a GRC do not have protection in relation to pregnancy under the characteristics of “pregnancy and maternity” or sex.

- Positive-action measures such as “women-only” shortlists and other measures aimed at increasing female participation must include males with a GRC.

- Data collection: “When data are broken down by legal not biological sex, the result may seriously distort or impoverish our understanding of social and medical phenomena.”

We have highlighted a 12th issue: women’s charities. Not having a clear protected characteristic of sex makes it difficult for single-sex charities (including those concerned with violence against women) to operate effectively. This has thrown organisations in the women’s sector into turmoil, leaving them riven by conflict and fearing legal risks. All this distracts them from their vital work.

For the Equality Act to work effectively all of these issues need to be addressed. This is not a question of adding more exceptions; what is needed is one simple, clear amendment to clarify that for the purposes of this law, sex means sex.

What needs to happen next?

On 6th December 2023, in the House of Commons, the Minister for Women and Equalities said:

“The law is no longer clear. In fact, I would go so far as to say that the law is now a mess because of changing times. We need to provide clarity. We cannot assume that the wording as was intended in 2004 and 2010 still works in 2023, and we are carrying out work to fix that.”

Whatever action the government takes to fix the law it should address all 12 adverse effects, and maintain coherence. We think the Government should now act urgently to amend the definition of woman and man in the Equality Act. It should ask Parliament to agree to amend the GRA 2004 to say:

“The fact that a person’s gender has become the acquired gender under this act does not affect the status of the person as a man or woman in relation to the protected characteristic of ’sex‘ in the Equality Act 2010.”

This could be done through secondary legislation using Section 23 of the Gender Recognition Act (which was intended for exactly such a purpose), or through primary fast-track legislation that achieves the same result.

This would not remove the general prohibition on discrimination against trans people, as there is a separate protected characteristic of gender reassignment. It would resolve the 12 adverse effects and maintain a single clear coherent definition of sex in the Equality Act.

The Istanbul Convention

The UK has ratified the Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating domestic violence and violence against women. It is based on the recognition that:

“the realisation of de jure and de facto equality between women and men is a key element in the prevention of violence against women.”

Istanbul convention

The convention requires parties to take legislative and other measures to prohibit discrimination against women, and to provide specialist support services to women who are the victims of sexual and domestic violence. The need for specialist services for women is based not only on the practical need to keep vulnerable women safe from men who might attack or exploit them, but also on the fundamentally different experiences, disadvantages and needs of women as victims of violence.

In January the Group of Experts on Action against Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (GREVIO) will be visiting the UK. The UK Government and the Equality and Human Rights Commission will have to explain that the current position in law is that the Equality Act 2010 does not recognise that women (female people) are a group with particular needs and disadvantages that are different from those of male people who have a GRC. This undermines women’s services.

Failing to address the problem with the GRA and the Equality Act puts the UK at risk of breaching its commitments under the Istanbul Convention.