Sex matters in changing rooms

A story was reported in the media last week about Charlie, a “non-binary teenager”, being excluded from the fitting rooms of the women’s clothing retailer Monsoon in Birmingham.

According to the report, Charlie (for avoidance of doubt, a young man) was told to leave the cubicle and then the overall fitting room as “the store did not allow men in there” and “they were getting complaints from women with children”. Charlie’s companion, also “non-binary” (apparently a young woman), was allowed to stay.

After Charlie complained on social media, Monsoon apologised (and offered a free prom dress). The company said that its fitting rooms are “open and available to all our customers”, adding that it has now “opened an investigation into the incident”.

We have written to Monsoon urging it to think again about this policy.

If you are or have been a Monsoon customer, and value female-only changing rooms, use our two-minute form to tell the company how you feel.

The Birmingham store is particularly popular with Muslim women, and Monsoon advertises “Eid dresses” on its website.

In responding to female customers who have complained, Monsoon has so far given this unsatisfactory response:

What does the law say?

Monsoon’s policy appears to reflect the Statutory Code of Practice, which tells service providers they must take a “case by case” approach to including or excluding individuals who wish to use opposite-sex services. Monsoon’s experience demonstrates why this policy is unworkable in practice.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission has recently produced new guidance that does not include the “case-by-case” recommendation.

As the new EHRC guidance sets out, the law is clear that service providers can offer single-sex and separate-sex services in a range of everyday situations set out in the Equality Act, as long as providing the service in this way is a “proportionate means to a legitimate aim”.

Monsoon’s legitimate aim is to be a women’s clothing retailer and as part of this to allow customers to try on its clothing in store with comfort, dignity and privacy.

There are two criteria that are relevant to Monsoon’s fitting rooms:

“The service is likely to be used by more than one person at the same time and a woman might reasonably object to the presence of a man (or vice versa).”

“The level of need for the services makes it not reasonably practicable to provide separate services for each sex.”

Monsoon could clearly argue that while it recognises that there are men (such as cross-dressers, transsexuals and gender non-conforming males) who wish to wear Monsoon clothing, the level of demand means that it is not reasonably practicable to provide separate fitting rooms that include males. It is therefore lawful to provide only a women’s fitting room, and good practice to communicate this clearly through policies, signage and training for staff.

“Gender reassignment” is a protected characteristic in the Equality Act, and the guidance states that service providers should consider the rights and needs of people who are covered by this characteristic (“trans” people) but that does not mean they are the opposite sex.

In developing policies services providers should be aware that their staff should not:

- ask a trans person for personal information like a Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC)

- treat someone differently because they have or haven’t got a GRC

- share personal information about a person’s trans identity or GRC with other customers

- make assumptions about whether a person is really trans based on their appearance or clothing.

What this means in practice is that it is not possible to have a rule or policy that fairly and consistently treats some males differently from others, allowing them to access female-only spaces based on factors such as clothing or appearance, medical diagnsosis, self-declaration or legal “sex change”.

Rather than trying to make impossible case-by-case decisions, service providers should consider their overall mix of single-sex and unisex spaces when planning their service in relation to its legitimate aims.

The new EHRC guidance gives examples of good practice “trans inclusion” that reflect this:

- Have both mixed-sex and female-only options (e.g. exercise classes)

- Have both single-user unisex and male and female options (e.g. gym changing rooms, toilets in a larger building)

- Have only “gender neutral” options (e.g. a small cafe with self-contained toilets with hand basins)

It also makes clear that it is not always possible or proportionate to provide a unisex or gender-neutral option alongside a service that is for one sex, and it is lawful to simply say that this particular service is single sex. The example it gives for this are a women’s refuge and a rape counselling service.

But the EHRC, unhelpfully for Monsoon, provides an example that diverges from these principles:

“A women’s clothes shop has changing areas for customers to try on garments in cubicles. The shop decides that it is not necessary to exclude trans women as the privacy and decency of all users can be assured by the provision of those separate cubicles.”

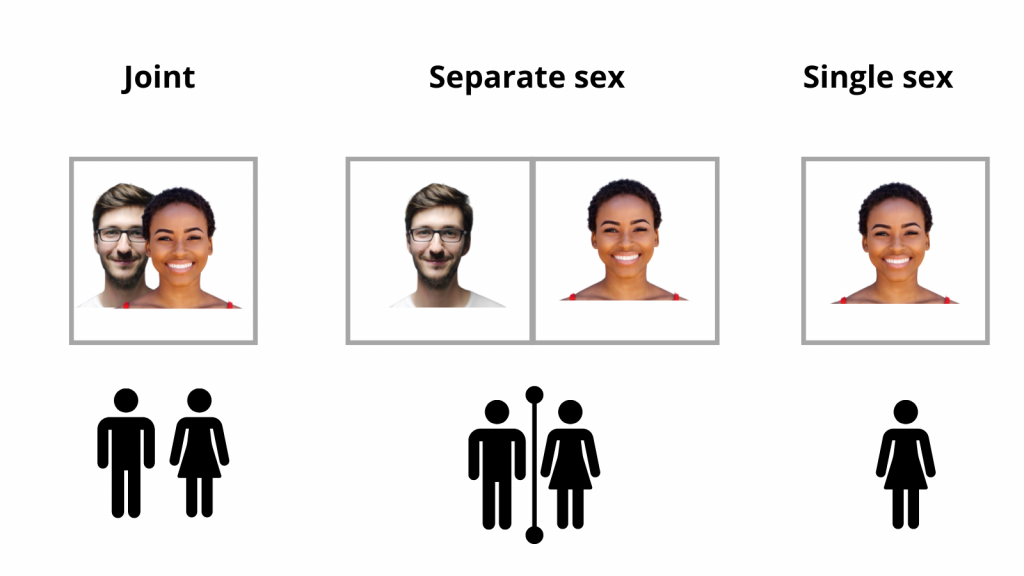

This example is unclear. Some clothing shops do provide a joint (mixed-sex or unisex) changing area. Others have separate male and female changing areas. Others have only changing room only for men or women. The difference is not cubicles, but signage.

A situation where “a woman might reasonably object to the presence of a man” (as the female customers at Monsoon in Birmingham did) does not depend on whether there are cubicles, but whether they have been led to believe that the area is single-sex.

A women’s clothing shop is likely to be assumed by customers to be offering a female-only changing area (even if it lacks explicit signage). It is preferable to have a clear policy and signs so that everyone knows what to expect. Providing spaces with ambiguous rules is likely to lead to conflict, uncertainty or humiliation.

A retailer cannot expect its staff or customers to be able differentiate between a “trans women”, a cross-dresser, a man who identifies as “non-binary”, or any other man in explaining the rules about whether a space is female-only or mixed-sex. People who identify as trans should be expected to follow rules in the same way as others.

If Monsoon is really inviting women and children to undress, and try on Eid dresses, in spaces that are mixed sex and “open and available to all our customers” it should communicate this clearly. But it would be far more sensible for it to put up clear signs that the changing rooms are for women and accompanied children only. Men (including those that identify as “trans women”) who wish to wear its clothing are welcome to buy them and try them on at home. This would be lawful as a proportionate means to a legitimate aim.